Equal Access to Public Accommodations

Although integrating the nation's schools was the first priority of the civil rights movement, the denial of equal access to public accommodations affected all black people, not just students. African Americans could not use restaurants, bathrooms, water fountains, public parks, beaches, or swimming pools used by whites. They had to use separate entrances to doctor's offices and sit in separate waiting rooms. They could only sit in the balcony, or in other designated areas, of theaters. They had to ride at the back of streetcars and buses.

On July 14, 1944, Irene Morgan boarded a bus from Gloucester, Virginia, to Baltimore and was passing through Saluda when she was told she was defying Virginia's 1930 law segregating seating by rows. She refused to move and was ejected. A state court rejected her argument, but in 1946 the U.S. Supreme Court took up the case and ruled that Virginia had no right to impose segregation beyond its borders. The decision made segregation on interstate bus travel illegal. It took Rosa Parks's similar refusal in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955 to extend the same principle to bus travel within a state.

In 1960, in Boynton v. Virginia, the Supreme Court extended the Morgan ruling to bus terminals used in interstate bus service. Nonetheless, many black people were ejected or arrested when they tried to integrate such facilities. In 1961, hundreds of volunteers from across the country traveled to the South to test compliance with the Boynton decision by riding from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans. Known collectively as the Freedom Riders, they encountered little opposition beyond words as they traveled through Virginia. Violent resistance, however, erupted elsewhere, including in Alabama, where buses were set on fire.

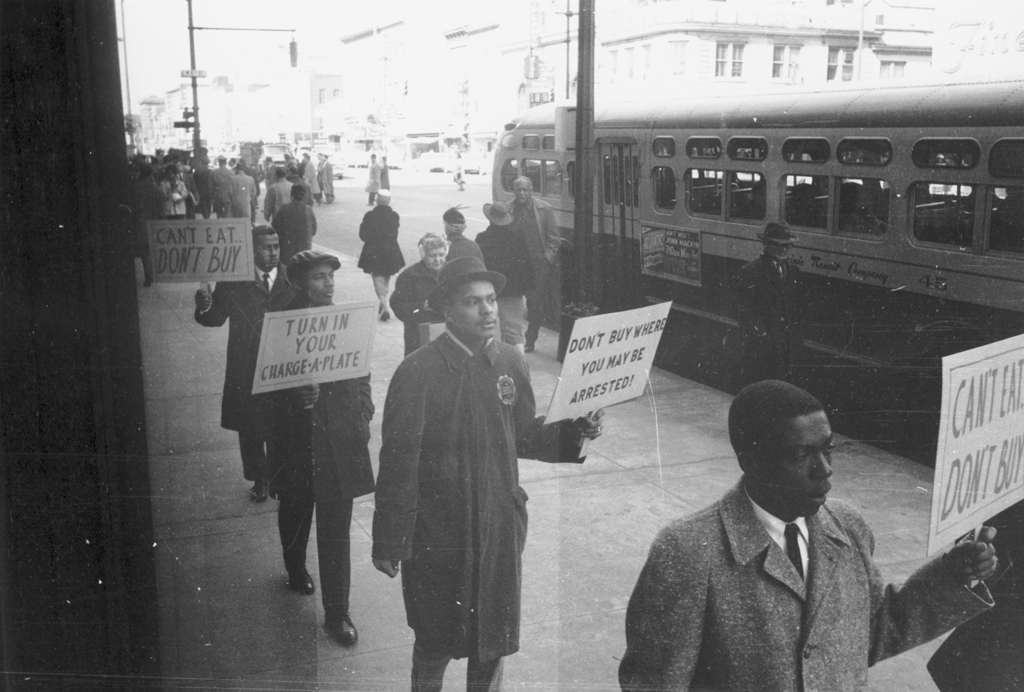

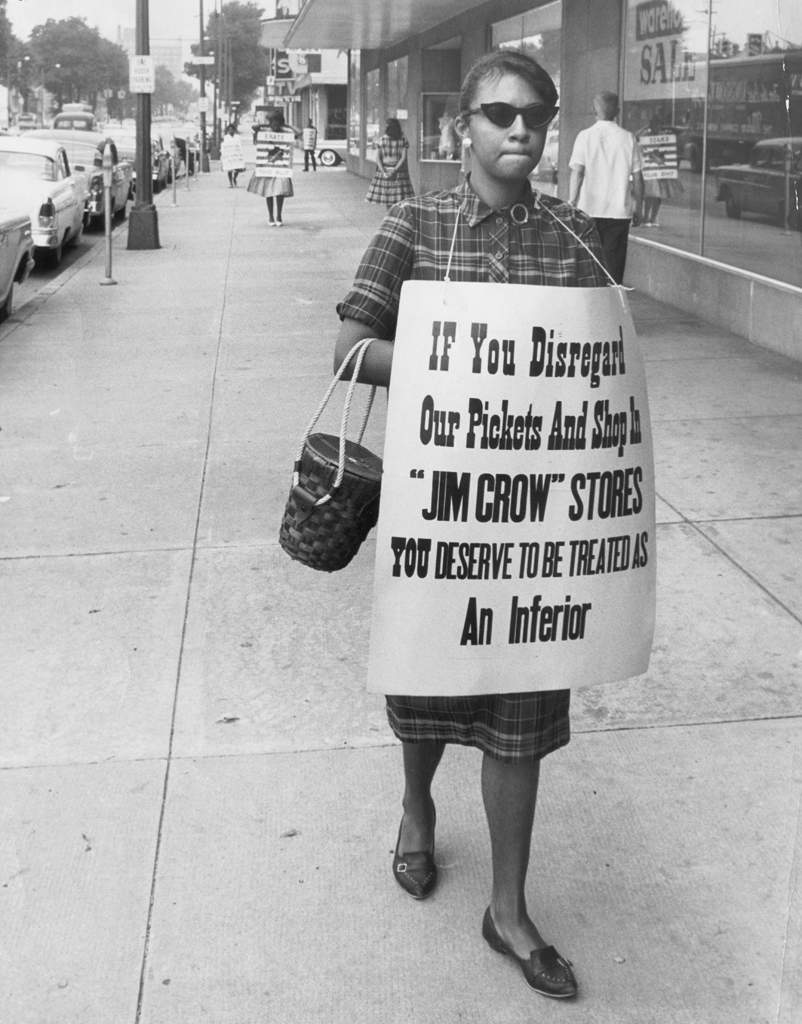

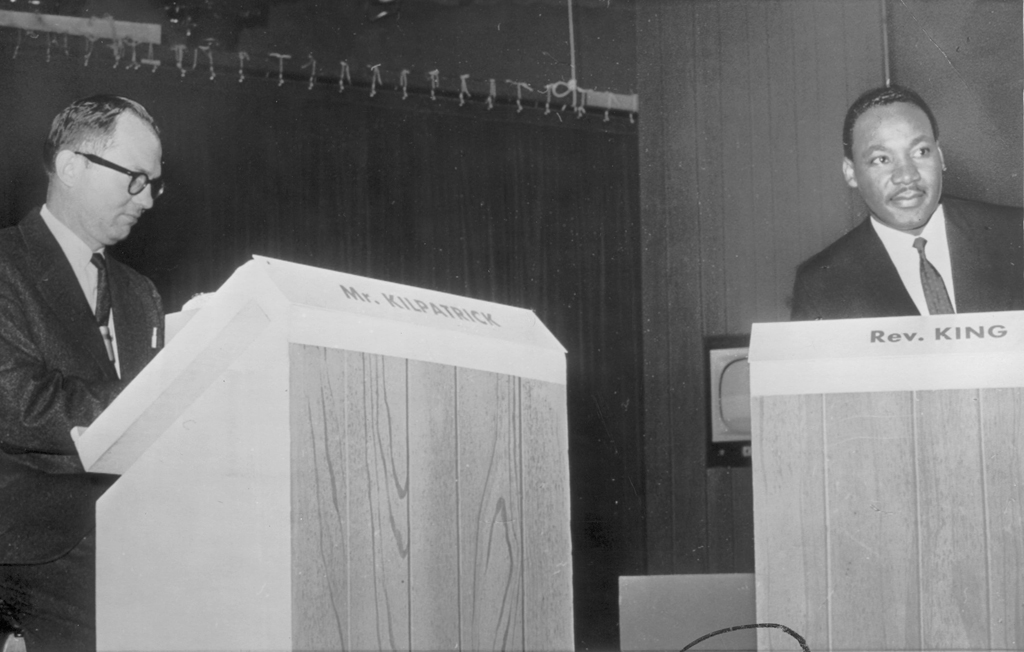

Students often argued that the movement should turn to nonviolent direct action in the streets rather than legal battles in courtrooms. One result of their effort were the lunch counter sit-ins, which began in 1960. Martin Luther King encouraged this "revolt against the apathy and complacency of adults in the Negro community, against Negroes in the middle class who indulge in buying cars and homes instead of taking on the great cause that will really solve their problems."

The sit-in tactic was borrowed from the labor movement, where it was used successfully in the 1930s in the auto and steel industries. Workers sat down on the job, preventing management or replacement workers from resuming production. At lunch counters, protesters—mostly black and white students—occupied seats on the principle "sit until served." They were not served, but as the seats were occupied, neither were any whites, and the businesses lost money. By the end of 1961, Woolworth's and other chain stores had desegregated their lunch counters. However, not all store owners gave in. It took the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to ban racial segregation "by businesses offering food, lodging, gasoline, or entertainment to the public."