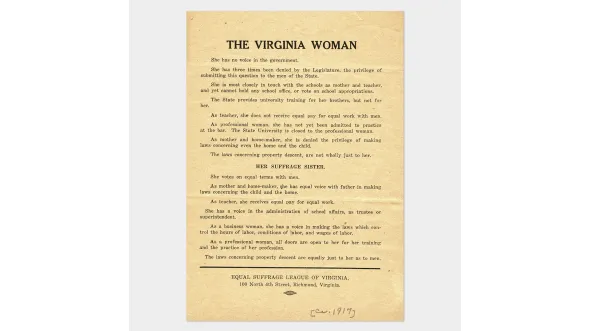

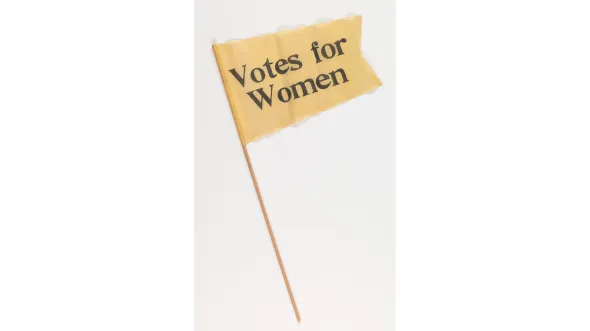

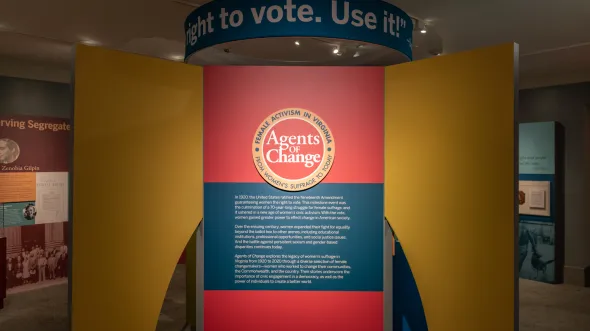

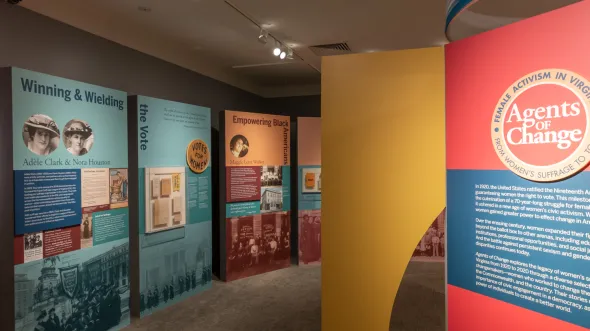

About the Exhibition: The passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 radically re-defined the meaning of American democracy by banning gender-based restrictions on voting. This landmark legislation marked the culmination of a concerted fight for women’s suffrage and heralded a new age of female participation in American civic life.

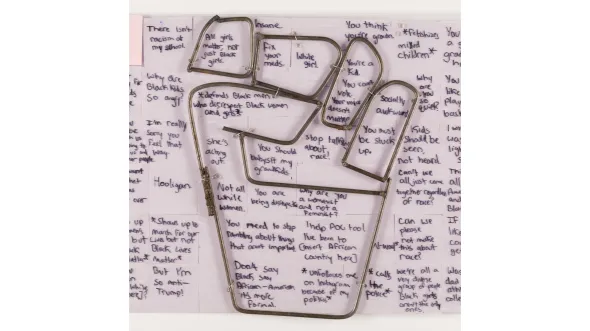

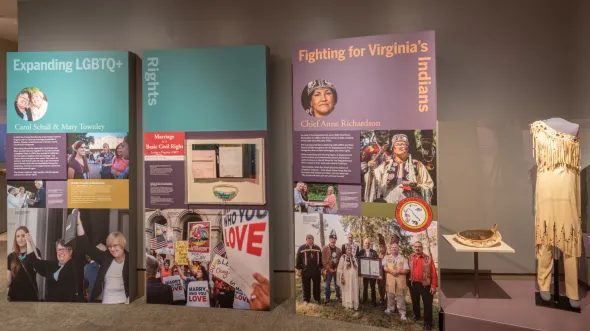

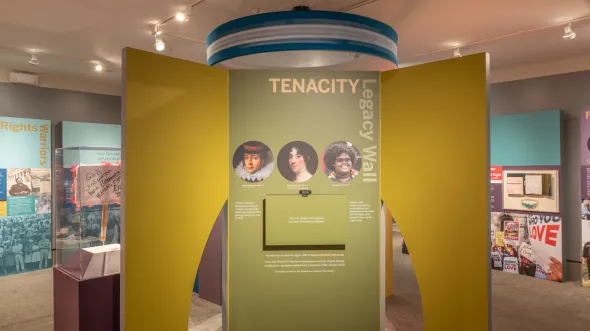

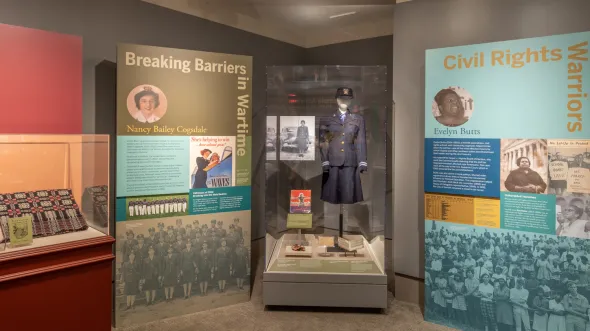

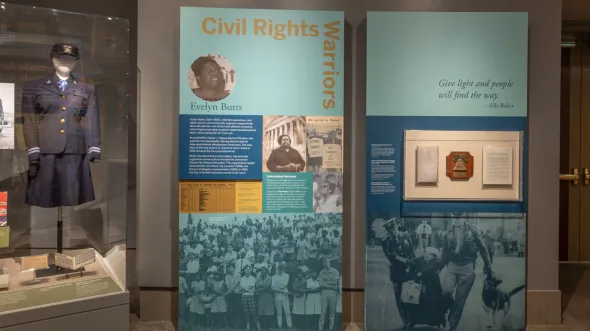

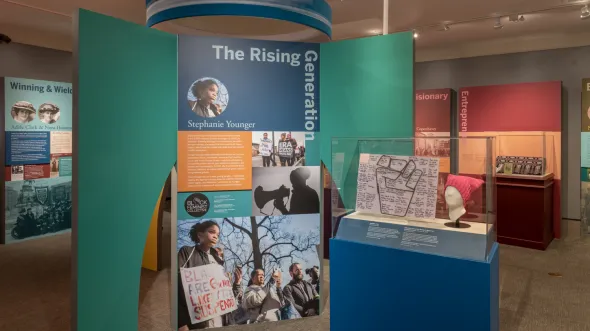

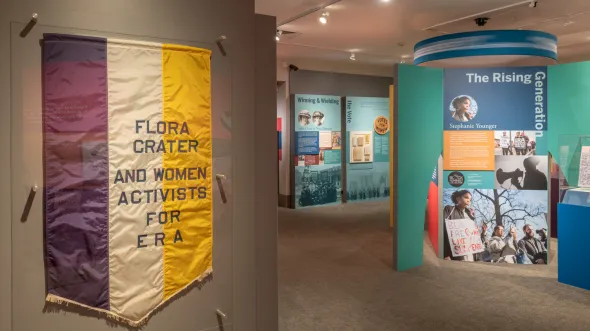

Organized in conjunction with the statewide Women’s Suffrage Centennial, this exhibition featured artifacts from the museum’s vast collections and new acquisitions made through a major collecting initiative, celebrated a century of women’s social and political activism in the Commonwealth. Highlighting the efforts and impact of a selection of female change-makers these women brought about positive change in their communities, the Commonwealth, and the nation. They also created new models of female empowerment and new opportunities for women—ultimately fostering a more inclusive and equal society.

See where the Traveling Exhibition is on display.

Thank you to our exhibition sponsors: The E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation and Mr. and Mrs. G. Gilmer Minor III.