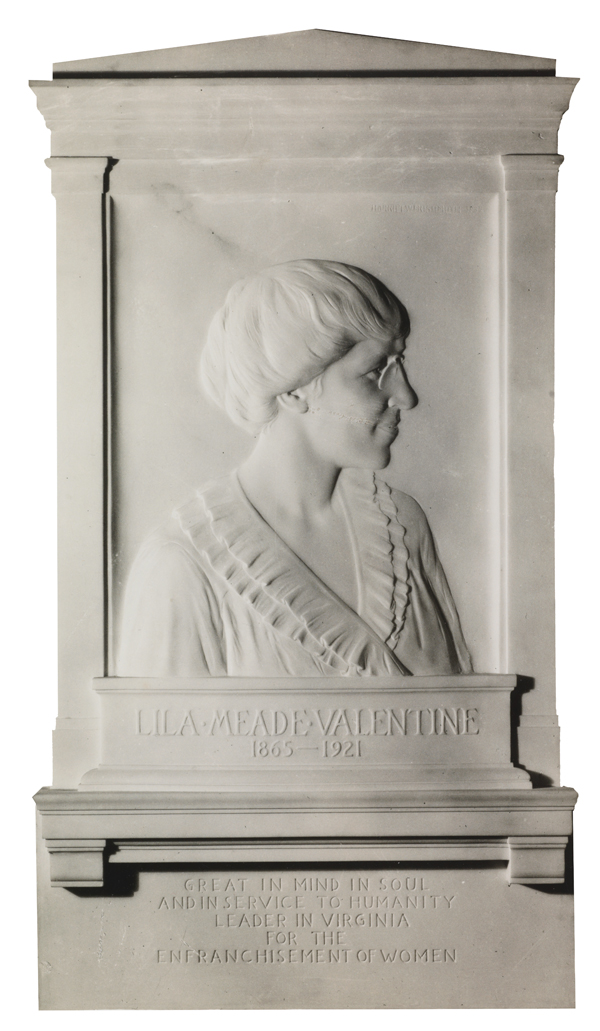

The Equal Suffrage League (ESL) of Virginia was founded in 1909, as women in the commonwealth expanded their fight for the right to vote. Lila Meade Valentine, as the first president of the league, traveled throughout the state to raise public awareness and build support for women’s suffrage. Other prominent participants included authors Ellen Glasgow and Mary Johnston, education activist Mary Munford, and artists Nora Houston and Adèle Clark. However, the ESL was an all-white organization—no Black women were admitted.

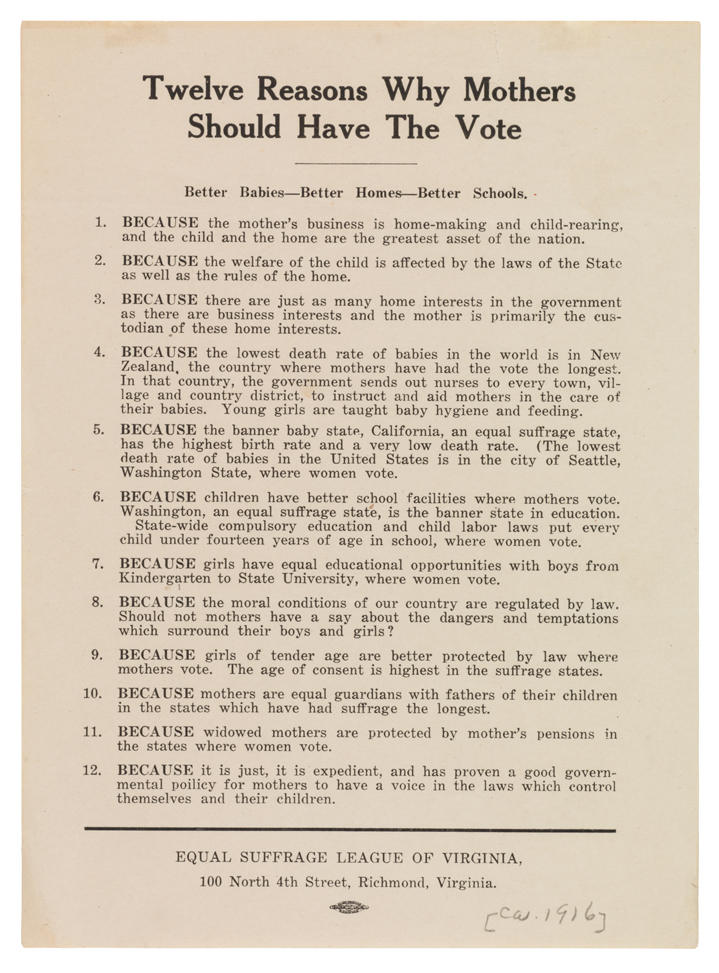

The ESL worked tirelessly for a decade, but the group failed in its efforts to convince state representatives that women should have the vote. Other southern legislatures, including Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina, also voted to keep women away from the polls.

The issue of race presented a major problem for the suffrage movement in Virginia. The ESL initially waffled on the question of Black women being given the right to vote, but eventually the group rejected the idea and toed the line of Jim Crow politics. Some white activists, including Lila Meade Valentine, excused their tactic by emphasizing it was politically expedient rather than a matter of principle. Another stumbling block for women’s suffrage was its close ties to the labor movement and its call for legislation to protect women and children from the exploitation of sweatshops. All of ESL’s efforts were complicated by Virginia’s one-party rule, which made exploiting differences between political parties impossible. After years of defeat at the state level, the group switched tactics and focused on winning Congressional passage of the amendment.

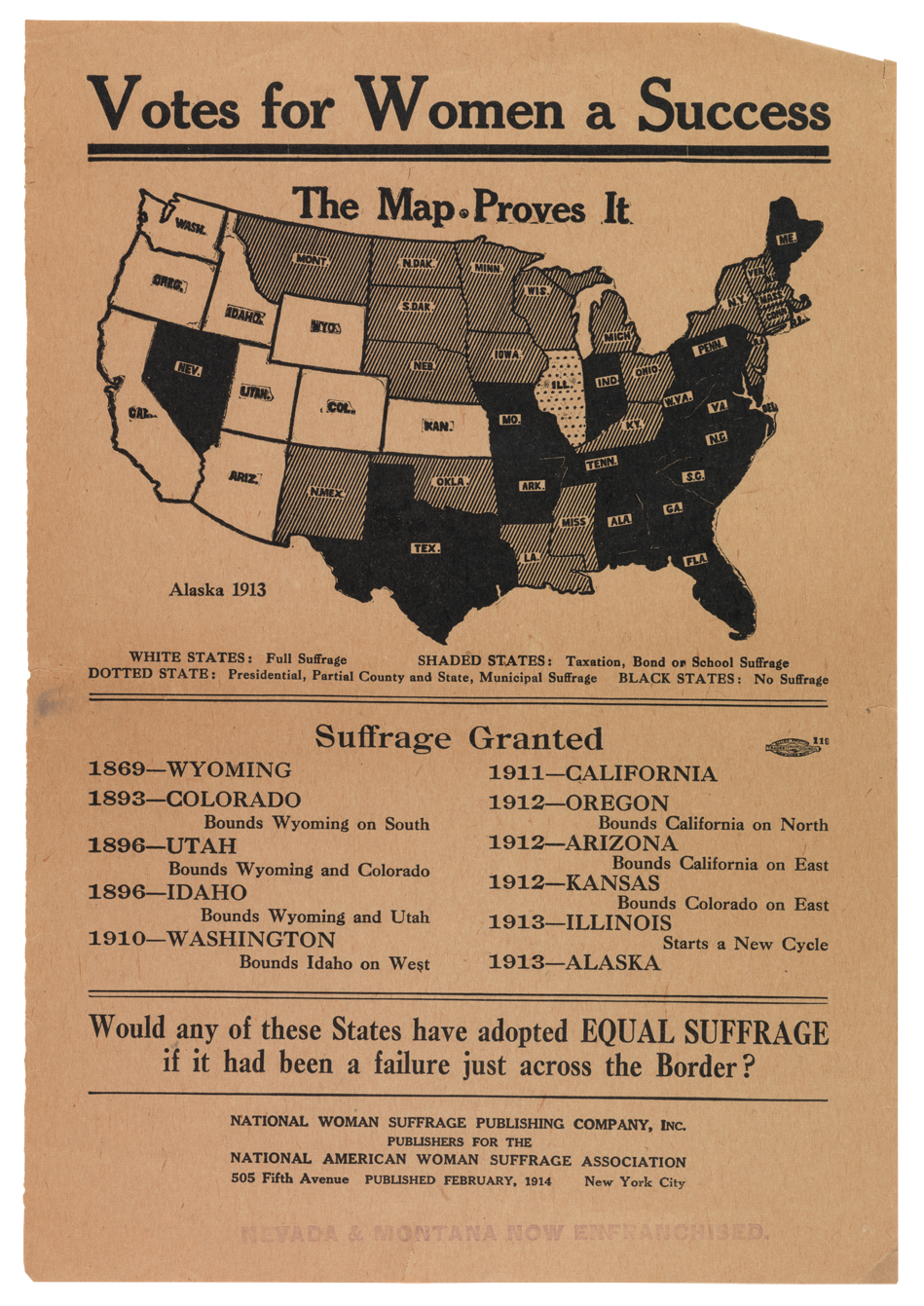

Women in Virginia gained the right to vote in 1920 with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It passed without Virginia’s support—and the General Assembly did not officially adopt the amendment until 1952.