During the last few decades of the 1800s, life for Virginian women was much the same as it was for women across America. White males were heads of their households, and exercised complete authority over their dependents. Because Virginia was a predominantly agricultural society, many women lived and worked on farms. Unlike their northern counterparts, Virginian women often bore five to six living children and lead lives proscribed by the traditions and cycles of rural society.

Women in Virginia

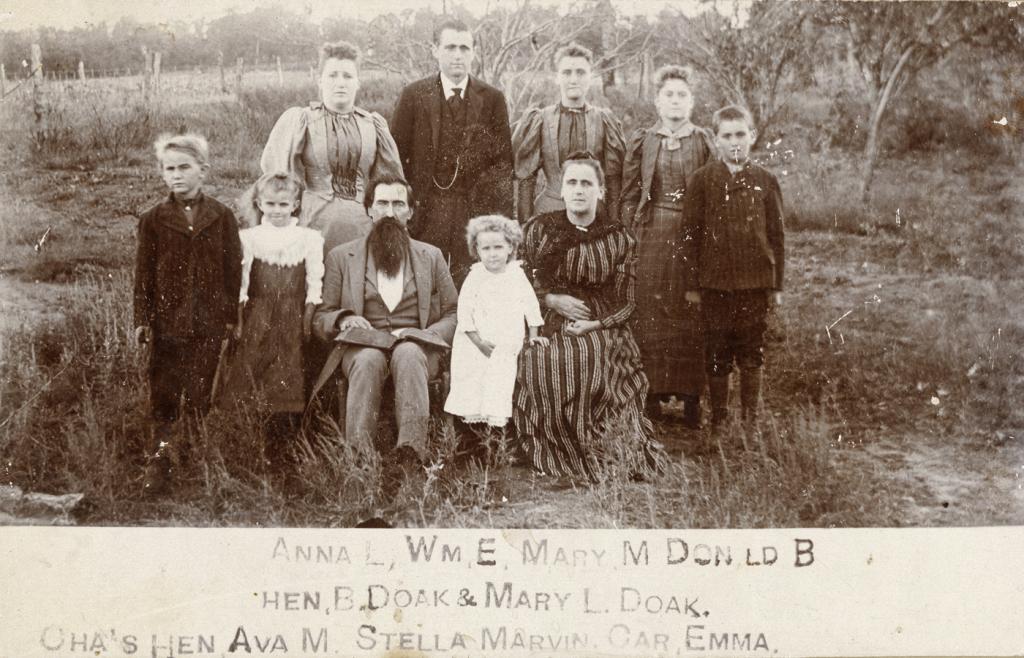

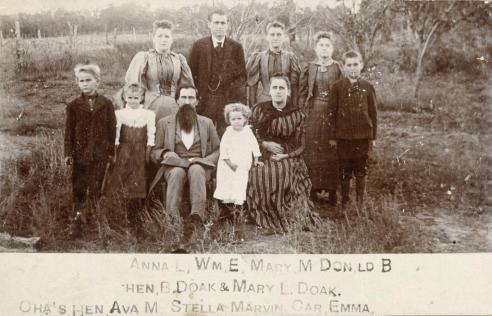

Doak Family

Sorting Peanuts, Smithfield, c. 1913

As was frequently the case in the South, gender issues in Virginia were complicated by race relations. For black women, Reconstruction was a time of rapid change. Isolation and poverty forced newly freed black women to seek employment in the homes and fields of whites. This was particularly true in southeastern Virginia, where peanuts had replaced tobacco as the main cash crop. Highly valued for their versatility, peanuts brought much-needed wealth to the previously depressed Tidewater area, and many farmers came to rely on sharecroppers to help increase their profits.

While rural women labored on farms, wealthy women began to explore spheres previously unavailable to them. Women first ventured into politics through their involvement in benevolent societies, memorial organizations, and historic preservation groups. The United Daughters of the Confederacy, based in Richmond, was established in 1894 to honor the memory of those who served in the Confederacy. The Mount Vernon Ladies Association, created by Ann Pamela Cunningham in 1858, was charged with preserving the home of George Washington for antiquity. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia (APVA) was established, with a membership made up entirely of women from the Old Dominion. The APVA focused on preserving neglected historic sites throughout the commonwealth.

Women also found themselves compelled to enter the business world. Richmond native Maggie Lena Walker gained prominence after her keen organizational skills saved the floundering Independent Order of St. Luke from financial collapse. She established the association's newspaper, and founded the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank to help not only the Order's members, but the local black community as a whole. After a merger between St. Luke and another Richmond bank, Walker became the first woman to found and serve as president of a chartered bank in the United States.

One common factor impacting the lives of women—rich and poor alike—was the growth of urbanization and industrialization in Virginia. During the turn of the twentieth century, more women moved from rural areas into cities, often seeking employment outside of the family home. A large urban landscape created more diverse communities, which allowed women more flexibility in shaping their own lives.

Tobacco Factory, Richmond, c. 1912

While cities offered more options for employment, women's careers were heavily circumscribed by gender. Only certain professions were deemed appropriate for women, such as teaching, nursing, and textile work. Telephone companies initially hired young men as operators, but replaced them with women employees when customers complained of the men's rudeness. In many fields, it was considered improper for a woman to continue working after marriage.

Pay was also unequal between the sexes. In 1890, female tobacco workers received about $120 per year, roughly one half of a man’s salary. The same was true for textile workers, and female employees in most other industrial jobs. Regardless of these challenges, by 1900, 125,000 women were employed in Virginia as farmers, professionals, and salaried employees.

Even in cities, employment was more restricted for black women than their white counterparts. African American women often saw their careers limited to domestic tasks, and could only find work as nannies, laundresses or seamstresses. Manufacturing and commercial employment was also segregated by race, and rates of poverty were typically much higher among African American women.

Despite their differences, there was common cause shared by white and black women: female suffrage. There had been an effort to organize a suffrage club in Virginia, but by the turn of the twentieth century those attempts has failed to take root. A second, more successful attempt was made in 1909, with the creation of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia (ESL). Established in Richmond by Lila Meade Valentine, the club was initially small, but by 1916, its membership had grown to almost 16,000 individuals.

Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, Richmond, c. 1919

Despite its exponential growth, the ESL failed to convince state representatives of the importance of female suffrage. A major foil to the ESL's efforts was Virginia's one-party rule, which made exploiting differences between political parties impossible. The ESL also grappled with the issue of race—some members supported suffrage for all women, while others favored suffrage only for white women. Despite their trials, women across the nation celebrated the passage of the nineteenth amendment to the Constitution in 1920.

In the hundred years between the 1860s and the 1960s, the lives of women changed dramatically. The women's rights movement experienced many stops and starts; women struggled for ninety years to gain suffrage, and they fought for equality in the workplace into the late twentieth century. The feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s helped solidify the rights suffragists dreamed of decades earlier. Women today are less restricted by their gender and share many of the rights and privileges as men.

Teachers: Visit Teaching with Photographs for questions to ask your students about women's history in Virginia.