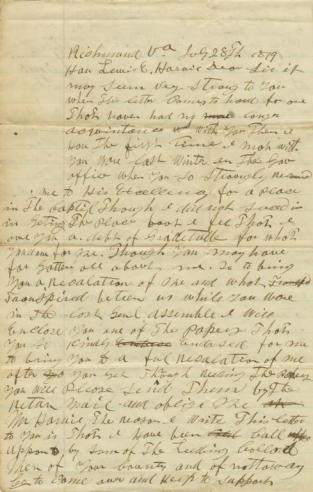

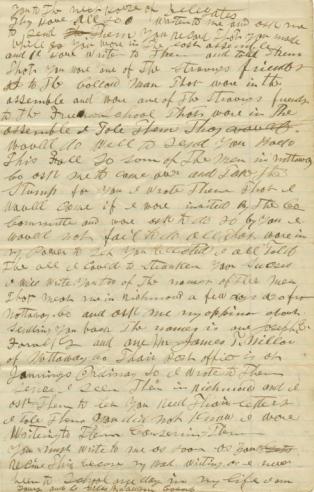

Letter, Giles B. Jackson, July 28, 1879

Letter, Giles B. Jackson, July 28, 1879

Introduction

Many people assume incorrectly that the close of Reconstruction meant the immediate curtailment of black political activity. However, the period between the end of Reconstruction and the turn of the twentieth century was a time when widespread black political participation often produced bi-racial coalition governments. In Virginia, the impact of black suffrage is most evident in the period from 1870 to 1885.

Historical Context

Before the Civil War, Virginia had borrowed $47 million to construct canals, railroads, and turnpikes. Although defeat invalidated all Confederate debt, the state's pre-war obligations were still valid. After the war, Virginia struggled to repay that indebtedness. During the 1870s, two factions materialized with distinctly different ideas about repayment. The "Funders" believed that the state should pay the entire amount, which was owed mostly to northern and European investors. They argued the importance of upholding the state’s honor and credit rating. By honoring the state's debts, Funders believed potential investors, whose capital was essential to the rebuilding process, would be more inclined to invest in Virginia. The "Readjusters," on the other hand, believed that part of Virginia's debt should be repudiated and that the newly created state of West Virginia should assume its share of the remainder. They argued that the war destroyed Virginia’s capacity to meet its obligations, and that the other southern states had successfully readjusted their pre-war debts.

The controversy grew as the state's financial situation worsened after the Panic of 1873. Appropriations for public services, especially the state's newly established public schools, dried up. Many people feared that payment of the debt would destroy the public education system. Funders and Readjusters both saw the public school system as a catalyst for change. While many Funders rejected public education as a waste of money and a threat to the traditional social order, many Readjusters, both black and white, believed public schools offered their children hope for a brighter future.

In 1879, the Readjusters gained control of the General Assembly and, two years later, captured the state house. In addition to scaling back the state debt, which they did in 1882, the Readjusters allocated more money for public services. Among their projects was the establishment of a teacher training school for blacks in Petersburg—the forerunner of Virginia State University.

It would be misleading to suggest that the Readjusters promoted racial harmony. Racial tensions existed and, in fact, eventually led to the demise of the party. But the movement does reveal that the political interests of African Americans and whites were not mutually exclusive.

Archival Context

This letter, written by Giles B. Jackson (1853–1924) to Lewis E. Harvie (1809?–1887), is part of a larger collection of Harvie family papers (Mss1H2636c) that includes more than 3,000 items. Lewis Harvie's letters and accounts represent roughly 75 percent of the collection, which also includes papers of a brother and several children. The collection came to the Virginia Historical Society in 1969, a gift of the estate of one of Harvie’s grandchildren, William Byrd Taylor.

Giles B. Jackson, a native of Goochland County, Virginia, was born enslaved. After the Civil War, he worked as a laborer for the Stewart family, a prominent Richmond family. Subsequently, he was employed in the law offices of William H. Beveridge. Beveridge tutored Jackson, who went on to become the first black attorney to practice before the Supreme Court of Virginia. Jackson organized and promoted the Jamestown Negro Exhibit at the Jamestown Tercentennial in 1907. A year later, he published A History of the Negro Race of the United States.

Lewis E. Harvie was a planter and railroad president who lived at Dykeland in Amelia County, Virginia. His correspondence, which largely pertains to post-Civil War politics, includes two letters written by Jackson. In the second, dated 30 September 1879, Jackson says that he never received a reply to his earlier letter, but adds "I was at the Capitol today to see Conl. F. G. Ruffin and he tole me you ware in this city last Sunday and wanted to see me." He then goes on to repeat the offer made in his first letter. From this, we can conclude that Harvie was seeking Jackson’s active support.

We do not know whether Jackson ever traveled to Amelia and Nottoway to speak on Harvie's behalf. We do know that Harvie lost the election.

The Document

In this letter, Jackson offers to "take the stump" in Harvie's behalf. This means he will campaign for Harvie by speaking at public gatherings. Your students will likely have a difficult time reading the letter because of poor spelling and handwriting. They may also be surprised by Jackson’s use of the word "collord." Draw their attention to the last sentence where Jackson writes, "Excuse my bad writing as I have never been to school one day in my life." Does this information affect the students' view of the author?

While Jackson is polite, he is not deferential toward Harvie. This suggests that Jackson sees theirs as a relationship based on mutual self-interest; Harvie did Jackson a favor and Jackson wants to pay him back. Jackson offers his services, but needs to be reimbursed for his expenses and, most tellingly, will only come if invited by the county committee and if Harvie asks.

Transcript

Richmond VA. July 28th 1879

Hon. Lewis E. Harvie Dear Sir it may seem very strang to you when this letter comes to hand for one that haven had no longer acquaintance with you then I have the first time I met with you ware last winter en the Gov[ernor’s] office when you so straungly recomned [recommended] me to His Excellency for a place in the Captil though I did not suced in in geting the place bout I fel that I owe you a debt of gradetude for what you done for me. Though you may have for gotten all about me. So to bring you a recalation of me and what transpired beteen us while you ware in the last Genl Assemble I will enclose you one of the papers that you so kindly enclosed for me to bring you to ful recalation of me after you get through reeding the papers you will please send them by the return mail and oblige me [.] Mr Harvie the reason I write this letter to you is that I have been call uppon by sum of the leeding collord men of your county and of nottoway Co to come over and help to support you to the next House of Delegates [.]They have all so writen to me and ask me to send them you record that you made while you wore in the last assemble and I have writen to them and told them that you wore one of the straunge friends to the collord Man that ware in the assemble and wore one of the straunge friends to the Free School that wore in the assemble[.] I tole them thay would do well to send you back this fall [.] So som of the men in nottoway Co ask me to come over and take the stump for you I wrote them that I would come if I wore invited by the Co Committee and wore ask to do so by you I would not fail to do all that ware in my power to get you elected [.] I all told the all I could to stranken you sucses[.] I will write you too of the names of the men that meat me in Richmond a few days ago from Nottoway Co and ask me my oppinon about sending you back[.] The names is one Joseph E. Farrell Jr and one Mr. James T. Miller of Nottoway Co Thair post office is at Jannings Ordinay [.] So I wrote to them sence I seen them in Richmond and I ask them to let you reed thair letters I tole them you did not know I were writeing to them conserning them you must write me as soon as you recive this [.] excuse my bad writing as I never been to school one day in my life I am yours and c Giles B. Jackson Colard

Activities: Teaching the Document

- Have your students refer to the appropriate timeline in their textbooks and introduce the letter to them. Give them the information in the heading (the place and date) and tell them that a black man is writing a white planter. Then ask them what they think the letter might be about.

- Have your students read the letter. What do they learn about Jackson? What do they learn about Harvie? What offer does Jackson make Harvie? Why?

- Describe the relationship between Harvie and Jackson? Are they friends? Did they have a relationship before the Civil War?

- Draw your students attention to the passage in the letter where Jackson writes, "I wrote Them That I would come if I wore invited by the Co Committee and wore ask to do so by you." What does Jackson mean by this?

- Jackson refers to Harvie as "one of the straunge friend to the Free School." Why do you think this is important to Jackson? What does he say about his own education?

- Tell your students that in 1955, the year that Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus, prominent southern historian C. Vann Woodward wrote a book titled, The Strange Career of Jim Crow. The book explored the period between the end of Reconstruction and the turn of the twentieth century, and examined occurrences like the one revealed in this letter. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. called Woodward's book "the Bible of the civil rights movement." Ask your students why Dr. King would find inspiration in the story of Giles B. Jackson and Lewis E. Harvie?

Suggested Reading

- Jane Dailey. Before Jim Crow: The Politics of Race in Postemancipation Virginia.

- James Tice Moore. Two Paths to the New South: The Virginia Debt Controversy, 1870–1883.

- Howard N. Rabinowitz. Race Relations in the Urban South, 1865–1890.

- C. Vann Woodward. The Strange Career of Jim Crow.

- Charles E. Wynes. Race Relations in Virginia, 1870–1902.

Standards of Learning

- VS. 8a

- VS. 8b

- USI. 10b

- USII. 3c

- VUS. 7c

- VUS. 8c