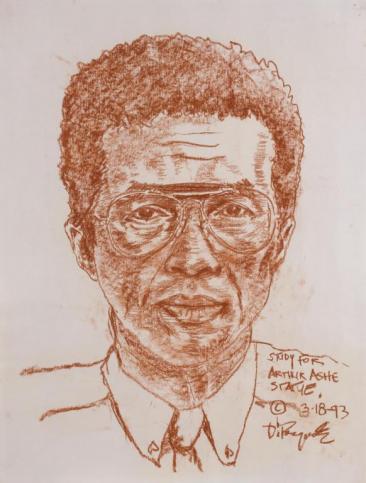

Sketch of Arthur Ashe, by Paul DiPasquale, 1993

Sketch of Arthur Ashe, by Paul DiPasquale, 1993

Sketch of Arthur Ashe, by Paul DiPasquale, 1993

Introduction | Historical Context | Archival Context | The Drawing | Activities | Suggested Reading | Standards of Learning

Introduction

After meeting Arthur Ashe in 1992, Paul DiPasquale, a sculptor known for public art, received permission to create a statue of the tennis champion. DiPasquale produced nine crayon and pencil studies for the statue the following year. After Ashe died in 1993, his wife, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, along with other family members, approved the portrait studies. Moutoussamy-Ashe also suggested the non-profit mentoring organization Virginia Heroes Incorporated as a possible source for funds. In 1993 the president and board of Virginia Heroes voted to raise $400,000 to complete the fabrication and installation of the twenty-four-foot high bronze and granite monument.

After meeting Arthur Ashe in 1992, Paul DiPasquale, a sculptor known for public art, received permission to create a statue of the tennis champion. DiPasquale produced nine crayon and pencil studies for the statue the following year. After Ashe died in 1993, his wife, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, along with other family members, approved the portrait studies. Moutoussamy-Ashe also suggested the non-profit mentoring organization Virginia Heroes Incorporated as a possible source for funds. In 1993 the president and board of Virginia Heroes voted to raise $400,000 to complete the fabrication and installation of the twenty-four-foot high bronze and granite monument.

The statue, located on Richmond's Monument Avenue, was unveiled on July 10, 1996. Had Ashe lived, he would have been fifty-three years old that day. The location of the statute sparked controversy. Critics opposed the site selected for the Ashe statue, a historic thoroughfare dotted with monuments to Confederate leaders. Southern heritage groups were the most vocal opponents, although a sizable minority of African Americans also objected to the placement of the statue because of Monument Avenue's association with the Confederacy.

Historical Context

Born on July 10, 1943, Arthur Ashe, Jr., was the son of Arthur Ashe, Sr., and Mattie Cordell Cunningham Ashe. At the age of twenty-eight, Mattie Ashe died. Arthur, Jr., was only six years old at the time. A year later, he met a Virginia Union University student, Ronald Charity, on the segregated Brook Road tennis courts where Charity was practicing. Charity taught Ashe how to play tennis. When he grew older, Ashe received additional training from Dr. Robert Walter "Whirlwind" Johnson of Lynchburg, Virginia. Johnson was a leader in the American Tennis Association, the black counterpart to the all-white United States Lawn Tennis Association. During the summer months, Ashe attended Johnson's camp, where Althea Gibson had also trained.

During his senior year in high school, Ashe relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, for additional tennis instruction. There, racial segregation was not as rigid. Ashe trained on indoor courts with hardwood surfaces, the challenge of which helped him develop. He also competed with whites as well as blacks. In 1960, Ashe became the first African American to win the national Junior Indoors Singles title. A year later, he won his second national title at the National Interscholastic Tournament, held at the University of Virginia. Ashe also graduated with the highest grades in his high school class. He accepted an athletic scholarship from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), from which he graduated in 1966 with a degree in business administration.

In 1967, Ashe entered the army for a two-year tour of duty. After leaving the army, he resumed his tennis career and soon became the top-ranked player in the world. In 1975, Arthur Ashe became the first African American to win the gentlemen's singles championship at Wimbledon.

In 1977 Ashe married Jeanne Moutoussamy, a photographer, and they had a daughter whom they named Camera. After heart surgery in 1979, Ashe announced his retirement from competitive tennis. In 1982 he was named Virginian of the Year by the Virginia Press Association. That same year, the city of Richmond named a new athletic center in his honor. In 1983 Ashe became co-founder of Artists and Athletes against Apartheid. Ashe researched and wrote A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African-American Athlete, a comprehensive three-volume work published in 1988. He conceived of a mentoring program for at-risk youth called Virginia Heroes in 1990. For his post-tennis career, he was selected Sportsman of the Year in 1992 by Sports Illustrated.

Ashe said that it was his demeanor that set him apart from other tennis players. "What it is, is controlled cool, in a way. Always have the situation under control, even in losing. Never betray an inward sense of defeat." Ashe became known as "The Iceman" by some of his colleagues because of his seeming nonchalance and detached attitude.

Monument Avenue and the erection of the Arthur Ashe Statue (Read the Richmond Times-Dispatch article)

Designated as a National Historic Landmark in December 1997, Monument Avenue represents the Old and the New South. Upon entering Richmond from the west along Monument Avenue, visitors are greeted at Roseneath Road by the Arthur Ashe statue. Unveiled in July 1996, the placement of the statute prompted international discussion and debate. Although Monument Avenue was never designated as a memorial to the Confederacy, in the minds of many it took on that role.

In 1887, Monument Avenue was proposed to encourage residential development west of the growing city and to announce Richmond's intentions of maintaining its role as the leading city of the South. The founding of the avenue coincided with national movements: the emerging City Beautiful movement encouraged the erection of monuments to national heroes; the American Renaissance movement inspired mostly romanticized interpretations of the nation's history, art, and architecture; and the cult of the Lost Cause venerated Confederate leaders. The Lee Monument was unveiled in 1890 after much debate about its location and sculptor (Marius-Jean-Antonin Mercie, a Frenchman, was eventually given the commission). Monument Avenue took on greater significance after the opening of the Museum of the Confederacy in the mid-1890s, solidifying the city and the avenue's role as a shrine to the Lost Cause. In 1907, two other monuments on the avenue were unveiled: one to J. E. B. Stuart and another to Jefferson Davis. A monument to Stonewall Jackson followed in 1919, and finally, in 1929, a monument was erected to honor Matthew Fontaine Maury.

Archival Context

Paul DiPasquale was commissioned by Virginia Heroes, Inc., to sculpt a statue of Arthur Ashe. As part of his preliminary work, DiPasquale made nine conte crayon studies of his subject. The drawings are approximately 26 inches by 21 inches. They are part of the Virginia Heroes Incorporated Collection, which was acquired by the Virginia Historical Society in 1997. While Virginia Heroes, Inc., owned the sketches, DiPasquale retained the copyright, and the Society needed to get his permission to use the drawings in this project.

The Drawing

Featured is one of nine crayon and pencil studies produced by Paul DiPasquale in 1993. (Copyright Paul DiPasquale)

Activities: Teaching the Document

- Remind your students that Paul DiPasquale met Arthur Ashe. Have them look closely at the sketch. What do they think the artist is trying to say about Ashe?

- Ask your students how the drawing (and the statue) might be different had the artist wanted the public to know that Ashe was a tennis champion?

- Have your students read the newspaper article concerning the placement of the Arthur Ashe statue on Monument Avenue. (Make sure that they understand that Monument Avenue is a historic boulevard lined mostly with grand turn-of-the-twentieth-century homes.) Have them identify and list as many arguments as they can both for and against the placement of the statue on Monument Avenue. Ask, "What is the best argument offered by those in favor of the statue's location?" "What is the best argument offered by those opposed?" (DiPasquale's plaster model of the statue, mentioned in the first paragraph of the article, is currently on display at the Virginia Historical Society.)

- Refer your students to other items on this site, specifically the 1866 broadside and the Jerome Baskett letter. Ask them about the issues that arise concerning the Civil War and memory. Do they see examples in their communities?

- Ask your students about how we as a society remember and commemorate the past. Can public art and historical commemorations ever please everyone? How would they deal with controversies that arise from events such as Jamestown 2007?

Suggested Reading

- Arthur Ashe and Frank Deford. Portrait in Motion.

- Arthur Ashe and Neil Amdur. Off the Court.

- Arthur Ashe. A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African American Athlete.

- Sarah Shields Driggs, Richard Guy Wilson, and Robert P. Winthrop. Richmond's Monument Avenue.

- Jack Salzman, David Lionel Smith, and Cornel West, editors. Encyclopedia of African American Culture and History, volume 1, pp. 204–07.

Standards of Learning

- VS. 8b

- VS. 9b

- VS. 9c

- USII. 8a

- VUS. 13a

- VUS. 13b

Richmond Times-Dispatch article

"Statue's Path Wasn't Smooth: Debates Focused on Symbolism, Heroes, Justice, Stie, Sculptor," Richmond Times–Dispatch, 8 July 1996

(Copyright Richmond Times-Dispatch, used with permission)

Interest Peaked a Year Ago | City Wouldn't Go for It, Wilder Says | One Statue Doesn't Have a Horse | Family Members Win Out | Sculptor's Work Challenged | Council Gets List of Demands

The city had accepted a statue of Ashe as a gift. There had also been an unveiling at the Ashe Center in December 1994, at which DiPasquale's plaster model of the Ashe statue first was shown.

But in June 1995, when the Planning Commission—at the urging of City Manager Robert C. Bobb—chose Monument Avenue at Roseneath Road as the monument's site, the level of public interest peaked.

Many people said that they had nothing against Ashe but that the monument didn't belong of the avenue of such Confederate heroes as Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson and Jefferson Davis.

DiPasquale said he never had thought of a site on Monument Avenue as he worked on the sculpture. Although he wanted the monument to be on the scale of those on the avenue, he didn't believe it would be put there.

City Wouldn't Go for It, Wilder Says

He said that others, including former Governor L. Douglas Wilder, had told him it belonged on the avenue but that the city would never accept it.

When a committee formed by Virginia Heroes was looking for sites and finally decided the statue should go on Monument Avenue, the members suggested Monument and Kent Road, far removed from the icons of the Confederacy.

In fact, DiPasquale said he and others looking for sites had joked about suggesting the intersection with Roseneath Road as a kind of red herring. That intersection is four blocks east of Kent and is inside the historic district that includes the monuments to the Confederate heroes. Certainly, no one would accept Ashe's monument inside the Civil War's second line of defense, they thought. "That would be the smokescreen so they would give us the site we wanted," he recalled.

Bobb had wanted to put the monument at the northern end of the Boulevard and rename the street for Ashe. When he saw that wasn't going to happen, he started scouting for sites on Monument Avenue.

He said he made many trips up and down the avenue while looking for locations. He didn't like the idea of putting it west of Interstate 195, removed from the other statues.

"The symbolism there would have been the statue was on the back of the bus," Bobb said during a recent interview in his office. "If all the other monuments were in the historic district, why not Ashe?"

In the weeks that followed the Planning Commission's decision, more than 400 people called or wrote City Hall, most of them to complain about the site. The majority said it was inappropriate to put a statue of a tennis player up the street from statues of soldiers on horses.

One Statue Doesn't Have a Horse

Actually, the monument closest to the Ashe statue honors a man who is not on horseback and is usually ignored in the controversy—Matthew Fontaine Maury, a Confederate-era oceanographer known as the "pathfinder of the seas" for mapping the oceans' currents.

One letter writer put her opposition this way: "Arthur Ashe, by most accounts, was a nice boy and a good tennis player. I would stop short of calling him a hero for being nice. A hero by most definitions is one who saves another's life."

She suggested other possible heroes for Monument Avenue, including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Tyler and Woodrow Wilson. "All of these people changed the course of history," she wrote.

Then-Mayor Leonidas B. Young had other ideas for the location of the monument. He suggested Byrd Park or downtown at the site of two abandoned department stores that would be torn down. Young, who is black, called Monument Avenue "a place where it has been perceived only white heroes go."

On the other hand, then-Councilman Chuck Richardson, who is black, said the Ashe Monument would "bring racial justice to Monument Avenue."

Another African-American man who grew up in Richmond said, "If I had seen a black figure [on Monument Avenue], that would have meant more to me than a bunch of horses and a cannon."

A white man said the Ashe monument would destroy the significance of the avenue. "The statues on that street are dedicated to one cause, one single cause," he said. Finally, the City Council decided to hold a public meeting on the matter.

Articles about the fight made newspapers across the country, including The Boston Globe, The Phoenix Gazette, The New York Times and the Sun-Sentinel of Fort Lauderdale, Fla. On July 17, more than 100 people spoke at the council's public hearing.

Some argued the statue didn't belong on the avenue because Ashe was a tennis player, not a hero. Some said it shouldn't go there because the street should be reserved for Civil War-era figures, and they even suggested a monument to blacks who fought for the Confederacy.

Several African-Americans said the statue shouldn't go on Monument Avenue because Ashe would be dishonored by having his statue so close to the shrines to people who fought for slavery.

Ashe was no fan of Monument Avenue. In Days of Grace, he wrote about "the huge, white First Baptist Church" on the avenue. "That church confirmed its domination and its strict racial identity by its presence on Richmond's Monument Avenue, the avenue of Confederate heroes, with its statues of Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis, J. E. B. Stuart, and Robert E. Lee."

In the end, though, Ashe's family members won. Ashe's brother, Johnnie, said the entire family favored the Monument Avenue site.

One speaker said that if the city put a statue of Ashe in Byrd Park, at the tennis courts, the city would be honoring a tennis player. A statue on Monument Avenue would honor the man.

In a recent interview, Johnnie Ashe said the family wanted the Monument Avenue site because the city spends money taking care of the statues there. "Why not put it someplace we know as a family it will be taken care of?"

He also said his brother was more than a tennis player and should be honored as such. "None of them [the Confederates] have made the contributions to our society Arthur has," he said during a telephone interview from his home in Atlanta.

For example, he said, "It was Arthur Ashe, Jr., who brought the system of apartheid in South Africa to light in the United States." That freed millions of people, Johnnie Ashe said. "I don't think any of our Confederate generals could touch that."

The council voted unanimously for Monument Avenue and Roseneath Road. The preservationists, who thought only Confederates belonged on the avenue, had lost.

Those who opposed putting an African-American on the avenue for racial reasons never had the nerve to speak publicly though many called news organizations with anonymous comments.

The historical preservationists, who contend that the avenue should be reserved for Confederates, have lost at every step along the way. They are continuing to fight the monument in court, with one man arguing that placing Ashe on the avenue would harm the local tourism industry.

After the council vote, a whole new group of people began an attack on DiPasquale's monument to Ashe.

Beverly Reynolds, a local art gallery owner, began circulating a petition asking for an international competition for a monument to Ashe. Her group of like-minded artists, critics, teachers and gallery owners called itself Citizens for Excellence in Public Art.

Reynolds's first official shot was an opinions piece in The Times-Dispatch on Oct. 3. She called DiPasquale's work "of very limited artistic merit." She said, essentially, that it was rammed down the city's throat without any kind of public process or review by art experts.

The group eventually developed a plan to spend about $1 million for an international competition. That idea was rejected by the City Council this year, but not before some acrimonious debate.

The debate reached a crescendo when Moutoussamy-Ashe had an open letter published on the opposite-editorial page in The Times-Dispatch on Jan 1. She reminded everyone that the whole process started when Ashe agreed to support an African-American Sports Hall of Fame in Richmond, and DiPasquale's statue was to be associated with that hall.

Opponents of DiPasquale's monument to Ashe seized on the letter as proof that the statue wasn't meant for Monument Avenue.

The Planning Commission held another meeting on the issue on Jan. 2 and gave Reynolds's group 60 days to come up with a plan to hold an international competition and to pay for it.

Young then negotiated a compromise. He and [long-time Ashe friend Richard] Chewning had scheduled a flight to New York to discuss matters with Moutoussamy-Ashe, but the airport was snowed in. Instead, they talked at length with her on the phone.

Provisions were that the DiPasquale monument would be placed on Monument Avenue until a new Ashe monument was chosen through an international competition. Then, the DiPasquale monument would be moved to an African-American Sports Hall of Fame, to be built somewhere in the city.

Citizens for Excellence in Public Art didn't like that plan. Members felt that if the hall of fame were never built—considered by many as a distinct possibility, given its $20-million price tag—DiPasquale's monument never would be moved.

The group eventually came up with a $1-million plan, with nearly $100,000 of the money going to fund various community meetings and other projects designed to involve city residents in picking the art.

Everything was going along well until March 25, when Citizens for Public Art presented a list of demands to the City Council. Council members scolded the group for having only one African-American among its members, and Young lectured the group's representatives on racial sensitivity.

Council rejected CEPA's plan. With that vote, the last viable obstacle to the monument was removed.

(Copyright Richmond Times-Dispatch, used with permission)