On November 11, 1921, known as Armistice Day and the anniversary of the end of World War I in 1918, the remains of an unidentified American casualty of that war were interred atop a hill overlooking Washington, D.C., in a “Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.” The tomb sits conspicuously in front of a massive neoclassical Memorial Amphitheater, a focal point of the landscape of Arlington Cemetery and the setting for memorial services of national significance. Those services are attended by presidents and other dignitaries.

The Memorial Amphitheater rivals in prominence the similarly impressive Arlington House, located less than half a mile to the north. Arlington House once dominated the entire landscape that still carries its name. It is often referred to as the Custis-Lee Mansion because it was built in 1803–17 by George Washington Parke Custis, George Washington’s step-grandson, and in 1857 it became the residence of his son-in-law, Robert E. Lee.

The 100th Anniversary of The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, situated in front of the Memorial Amphitheater.

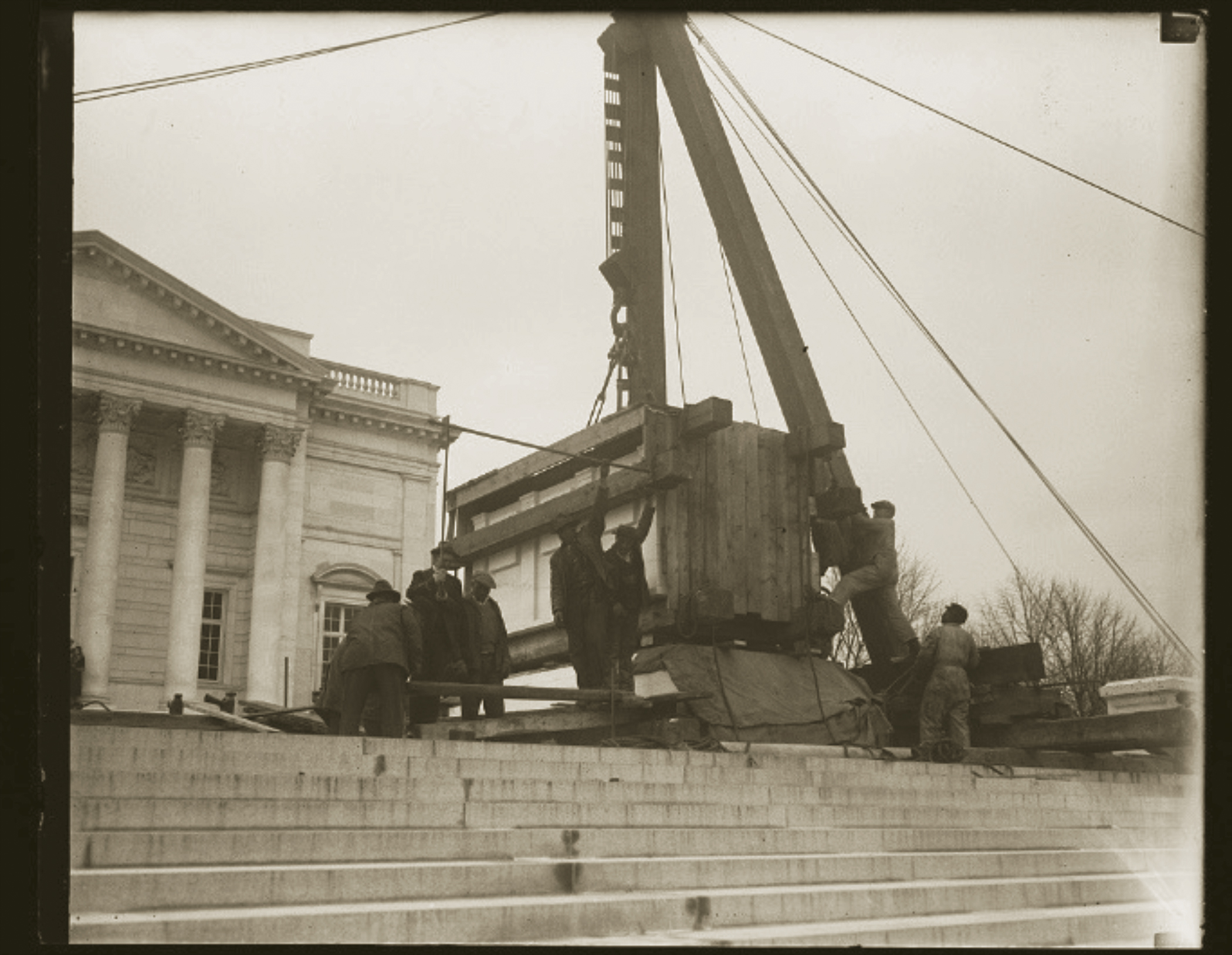

Installation of the superstructure that marks The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, 1932.

The amphitheater was completed in 1920, two years after the Great War ended. That conflict was not the motivation to build. Ground had been broken in 1915 when the existing James R. Tanner Amphitheater could no longer accommodate what were increasingly large audiences attending memorial services in the cemetery.

The impetus to add a burial place to the amphitheater complex came almost immediately, when in the same year of 1920 memorial tombs were created with fanfare in both France and Great Britain. Those nations had each lost more than a million soldiers, so many that reinterment would have been prohibitively complex and expensive. Instead, both nations constructed a tomb of the unknown soldier, one at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and the other inside Westminster Abbey in London.

The American repatriation policy allowed families of war casualties the option of burial in Europe or burial at home, at no expense to the next of kin. There remained, however, the issue of the countless unknown American soldiers who remained missing in action or whose remains were obliterated beyond identification. That same dilemma had been addressed following the American Civil War, less than half a mile away from the Memorial Amphitheater. A Tomb of the Civil War Unknown was dedicated in Arlington Cemetery in 1866.

Tomb of the Civil War Unknown.

Civil War carnage in northern Virginia had left thousands of remains. Bodies were hastily buried at battlefields or were simply left where they fell. In 1861, Congress authorized the purchase of cemetery land. By 1864, the need had so intensified that the U.S. Army Quartermaster General, Montgomery C. Meigs, a staunch Unionist whose son was killed in battle that year, seized 200 acres of the Arlington estate and transformed them into a military cemetery (now expanded to 624 acres). Meigs purposely made the home of Confederate general Robert E. Lee unusable by the proximity of burials to Arlington House. (In 1874, Lee’s son and heir, Custis Lee, sued the government and won when the Supreme Court ruled that the estate had been confiscated without due process. Custis Lee then sold the property back to the government).

A short distance to the west of Arlington House, Meigs placed a huge tomb, a masonry vault 20 feet in circumference and 20 feet deep. To mark the location, he had constructed above it a massive cenotaph (6 feet tall by 12 feet by 4 feet). Grisly records reveal that it contains compartments for different body parts: skulls, legs, arms, and ribs. An inscription on the side of the cenotaph details what is resting below: “the bones of 2,111 unknown soldiers gathered after the war from the fields of Bull Run and the route to the Rappahannock,” bones that “could not be identified.” Meigs had built what would prove to be a prototype for a World War I monument. That new tomb, however, would be nearly twice as tall (11 feet) and twice as wide (8 feet at the base).

In December 1920, no doubt aware of the unknown soldier tombs recently dedicated in Paris and London, New York congressman and World War I veteran Hamilton Fish, Jr., presented legislation “to bring home [for interment in Arlington] the body of an unknown American warrior who in himself represents no section, creed, or race in the late war and who typifies, moreover, the soul of America and the supreme sacrifice of her heroic dead.”

Honoring and Keeping Faith with America’s Missing Servicemen, 1958-1975.

To dramatize and publicize the selection of the American unknown, bodies of four unidentified soldiers were exhumed from different American military cemeteries in France, and a wounded and highly decorated veteran selected one of the four caskets, which was quickly shipped to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. On November 10, 1921, 90,000 visitors paid their respects. The next day, Armistice Day, a horse-drawn caisson carried the casket across the Potomac River to Arlington, where President Warren Harding officiated at a state funeral and interment.

A solid marble superstructure would mark the tomb, but Congress did not appropriate funding for it until 1926. A competition attracted 73 entries. Architect Lorimer Rich and sculptor Thomas Hudson Jones were awarded the commission. It took six additional years for 79 tons of marble to be quarried in Colorado, shipped to Arlington, and carved.

The tomb’s east end panel, which faces the river and city, depicts three classical figures: Peace holds a dove, while Victory extends an olive branch toward Valor, who holds a broken sword. The panel facing the amphitheater carries the inscription: “Here Rests in Honored Glory an American Soldier Known but to God.” The north and south panels are carved with wreaths and the names of six major American campaigns fought in the Great War. Just west of the sarcophagus, white marble slabs, laid flush with the terrace, cover crypts for unknowns from World War II and the Korean War. Between those is an empty crypt that once contained the remains of an unknown Vietnam War soldier. That crypt was emptied when DNA analysis identified the occupant (who was reinterred near his home.) Its slab cover is now inscribed, "Honoring and Keeping Faith with America's Missing Servicemen, 1958-1975."

Crypts and slabs to recognize the unidentified dead of future wars may never be needed. Medical advances in battlefield treatment significantly reduce the mortality count, and DNA analysis has nearly eliminated the centuries-old dilemma of identifying soldiers “known only to God.”