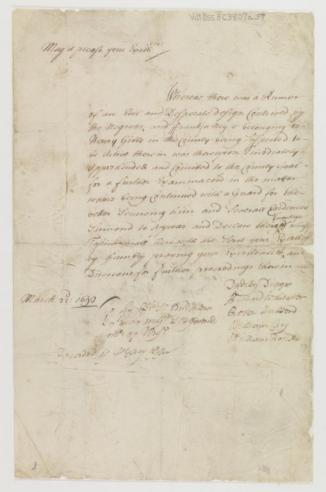

This affidavit, dated March 22, 1693, is from Warwick County (now Newport News), Virginia. It was submitted to Governor Sir Edmund Andros by Dudley Digges, Richard Whitaker, Cater Hubberd, William Cary, and William Rosser. The document informs the governor that Frank, a man of African descent enslaved by Henry Gibbs, has been jailed on suspicion of planning a slave uprising. The writers also seek the governor’s help in ferreting out the details of “a rumor of an evil and desperate design contrived by the Negroes.”

Historical Context:

The first enslaved Africans arrived in English North America in August of 1619. They were captured in West Central Africa in present-day Angola and sold to Portuguese slave traders, who had built a vast trade network among Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The African captives became part of a “cargo” of 350 people bound for the slave markets of Vera Cruz, Mexico. During the voyage, the White Lion and the Treasurer, two English privateers, attacked the Portuguese slave ship, seized about 50 enslaved Africans, and sailed for Virginia. In late August, the White Lion landed in the Virginia colony at Point Comfort (present-day Hampton) with “20 and odd Negroes,” which the captain sold to colonial leaders in exchange for food supplies. The Treasurer arrived a few days later with additional African captives. Thus began slavery in Virginia.

Very little is known about these First Arrivals. One of the few who appears—albeit briefly—in the historical record is a woman named Angela, who came aboard the Treasurer. A 1625 census of the Virginia colony lists her in the Jamestown household of William Pierce, a wealthy merchant and official. In 1619, slavery was relatively new in English colonies and, therefore, was not fully codified in English law and society. The first Africans in Virginia like Angela labored alongside white indentured servants—servants from England and Europe who agreed to work for a set period of time (usually 4 to 7 years) in exchange for their transatlantic transportation, food, and lodging. Although enslaved Africans and indentured servants shared the experiences of forced servitude, Black “servants” did not choose their lot and rarely were able to gain their freedom. One exceptional case among the first generation was Anthony and Mary Johnson, who were brought to Virginia in the early 1620s. After a period of bondage, they obtained their freedom, raised free children, became large landowners, and even owned their own laborers.

However, most early Africans in Virginia were held in lifelong bondage. And, as slavery became systematized in colonial society, their chances of becoming free declined. In 1640, John Punch, a Black servant, was sentenced to servitude “for the time of his natural life” for running away with two white indentured servants, who were punished with 4 additional years of service. Punch’s case marked the beginning of the legal codification of race-based slavery in Virginia. Racial hierarchies hardened with the passage of additional laws. Although Maryland and Massachusetts were the first American colonies to legalize slavery, it was the Virginia slave code, a series of laws enacted between 1662 and 1705, that became the standard that the other colonies followed.

In 1661, slavery was officially acknowledged in Virginia statutory law. A year later, Virginia’s government made slavery hereditary. In a radical break from British common law, children would inherit the free or enslaved status of their mothers, rather than their fathers. This law addressed the status of mixed-race children who were born to white men and Black women, a stigmatized but common occurrence given the gender hierarchies at the time. Enslaved women of childbearing age were valuable to slaveholders as they ensured a continual labor supply.

People of African descent rebelled against oppression in various ways, even at the risk of severe punishments. Acts of resistance prompted Virginia’s colonial leaders to enact additional laws restricting the rights of enslaved and free Black people. For example, laws precluded baptism as an avenue to freedom and decreed that slaveholders who killed disobedient slaves would not be charged with murder. Separate courts were established for enslaved people charged with capital crimes, denying them trial by jury. Even free Black people were denied the right to vote, testify in court, serve in militias, or buy white indentured servants.

Virginia’s system of slavery became more deeply entrenched with the growing number of people of African descent in the colony. Their numbers in proportion to white settlers remained relatively low for most of the 1600s. In 1670, Black Virginians made up about 5 ½ percent of the colony’s population, and white indentured servants comprised 80 percent of the workforce. These demographics shifted dramatically as England became more involved in the transatlantic slave trade, increasing the availability and profitability of enslaved African labor. In addition, improved economic conditions in England began to slow the migration of white indentured servants to America. By 1700, enslaved people represented 80 percent of Virginia’s labor force and, increasingly, forced labor was associated exclusively with Black skin. By the eve of the American Revolution, Black people comprised about 42 percent of the colony’s population.

These demographic changes fueled widespread fears of slave revolt or insurrection among white settlers. On many large and remote tobacco plantations, enslaved workers often greatly outnumbered white people. This affidavit of 1693 documents such fears as a group of white Virginians asks the colonial governor for assistance in the face of a perceived slave plot. In response to such fears, the legislature also tried to prevent insurrections with laws that prohibited enslaved people from carrying arms, congregating in large numbers, and leaving their plantations without written authorization. This document identifies Frank as a conspirator in a planned uprising. Although his fate is unknown, suspected participants were often subjected to harsh punishments—including death—to deter others from similar acts of rebellion.

Archival Context:

This document is part of a collection of Virginia County Court Records, 1642–1842. The collection consists of manuscript records removed from the courthouse of Charles City County in 1862 by the father of Arthur G. Fuller, who served as an officer in the United States Army. Included are affidavits, appraisals, bonds, complaints, deeds, indentures, inventories, judgments, marriage bonds, order books, orders, petitions, receipts, and wills of Charles City County. The collection was a gift of Arthur G. Fuller in 1901.