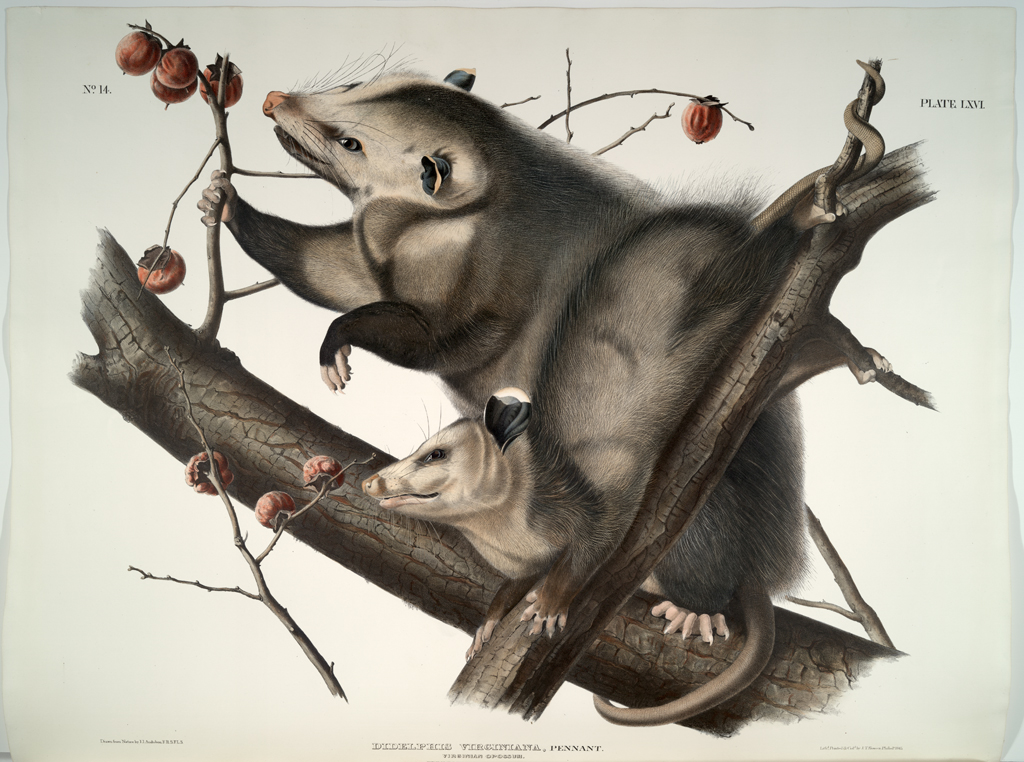

Following the success of his The Birds of America, John James Audubon began to gather material for an equally ambitious project to document the animal life of North America. The results of the artist-naturalist's years of research and field study was the Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, the outstanding work on American mammals of its time and a superb example of color lithography. Audubon included many frontier animals never before depicted, and his  landmark publication helped foster a public appreciation of American nature.

landmark publication helped foster a public appreciation of American nature.

Audubon collaborated with the Reverend John Bachman, a Lutheran minister and experienced student of mammalogy, who later wrote much of the scientific text. Audubon collected specimens sent to him by friends, and in 1843 he made a final expedition up the Missouri to do more field work. He envisioned Viviparous Quadrapeds (literally meaning four-footed mammals) as the definitive record of all North American mammals. Bachman warned Audubon, who was not a trained naturalist, that he had underestimated the scope of the mammal population, and they agreed to eliminate bats and marine animals. By 1846 Audubon's health was failing and his son, John Woodhouse, made substantial artistic contributions, eventually completing half the plates for Quadrapeds. Another son, Victor, served as editor and business manager.

Despite the difficulty of marketing colorplate books in America, Quadrapeds was a commercial success and was published in two sizes and several editions between 1845 and 1854. The elephant folio edition shown here contains a number of animals from Virginia such as this plate of the "Virginian Deer."