Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia was the first popular uprising in the American colonies. It was long viewed as an early revolt against English tyranny, which culminated in the war for independence one hundred years later. Perhaps the most notable purveyor of this view was President Thomas Jefferson, who came to regard Nathaniel Bacon as a patriot rather than a rebel. This interpretation of Bacon persisted, as evidenced by the unveiling of a memorial window in the powder Magazine at Colonial Williamsburg in 1900, and a few years later, the placing of a plaque in the Virginia Capitol commemorating Bacon as “A Great Patriot Leader of the Virginia People who died while defending their rights October 26, 1676.” Historians more recently have challenged this interpretation, pointing to Bacon’s effort to frame his rebellion as serving the interest of the Crown, as his intended target was Governor Berkeley and his elite supporters. The context and roots of the rebellion present a complex story of how and why it took place.

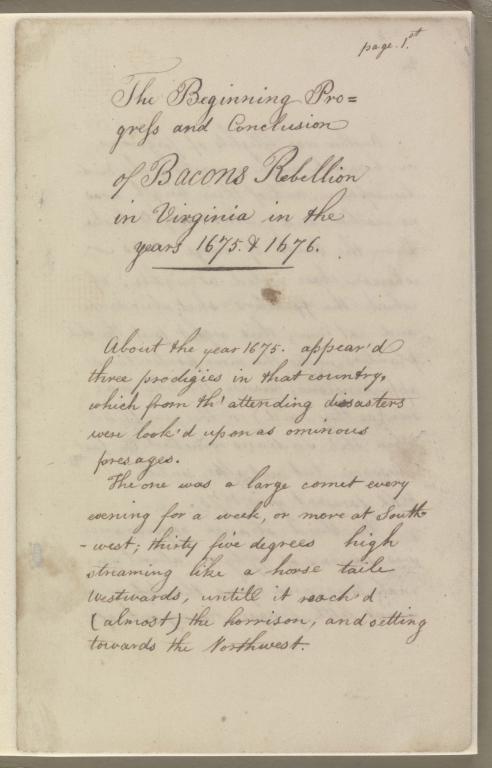

Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia in the years 1675 & 1676

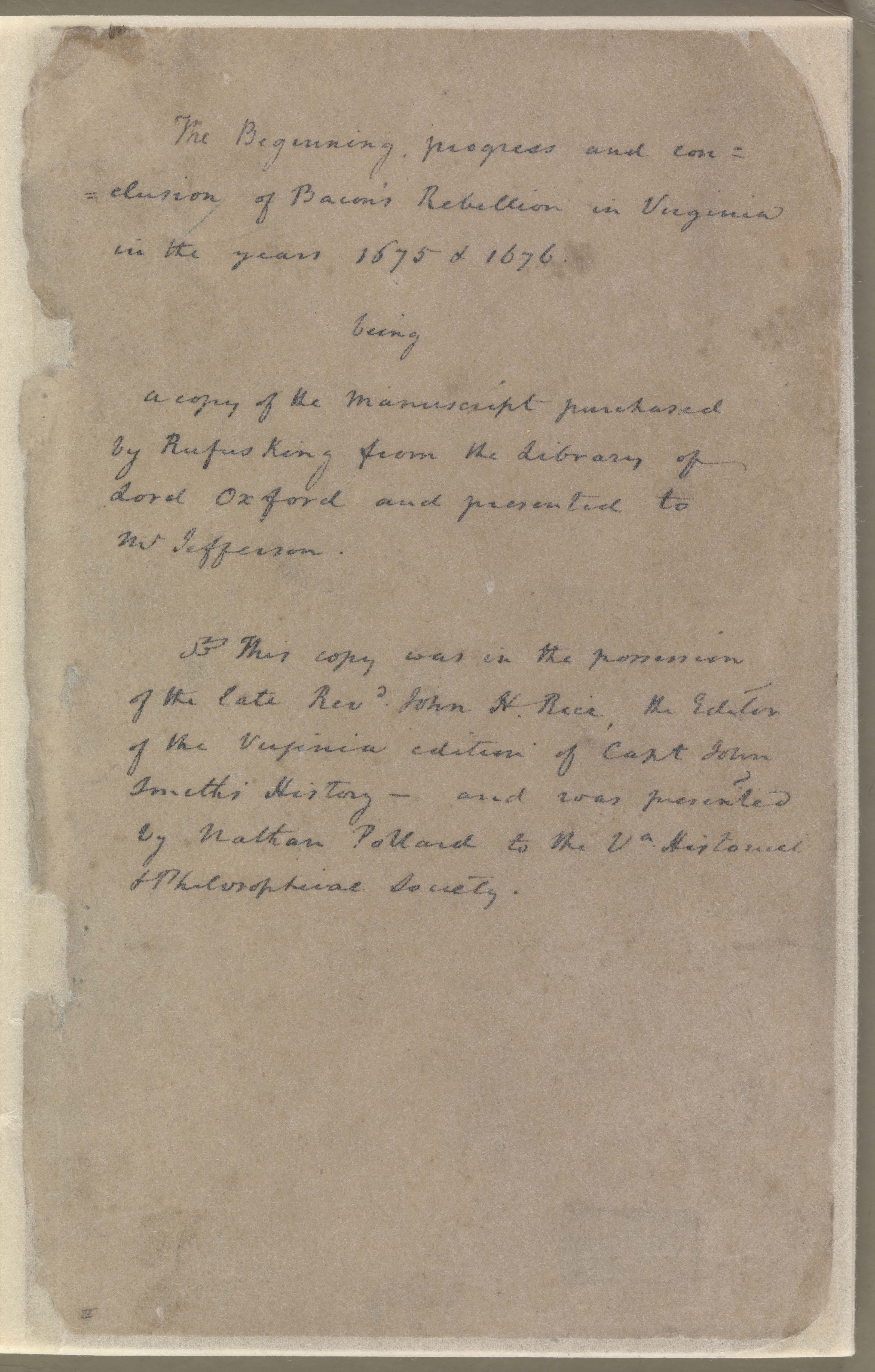

The beginning, progress, and conclusion of Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia in the years 1675 & 1676.

The uprising generally is depicted as a reaction to a perceived crisis in Virginia’s economic, social, and political order. Settlers on the frontier faced bad weather and poor returns from their crops. Virginians relied on tobacco as the only staple commodity, making them vulnerable to market fluctuations. Planters faced competition from Maryland and the Carolinas in an increasingly restricted market, as well as rising costs of manufactured goods resulting from England’s policy of mercantilism. Yet Bacon’s supporters were more disturbed by falling tobacco prices and high taxes than the protectionist policies in the Navigation Acts. Declining prices were caused largely by overplanting in Virginia. Taxes were paid with tobacco at the time, and unlike wealthy plantation owners who had an abundance of the crop, small planters struggled to meet the burden. Economic disparity between the gentry in eastern Virginia and the growing number of small planters, poor immigrants, and freed servants living on the frontier led to substantial discontent among the lower and middle classes. Additionally, most people had no part in political life, and those who did not own land could not vote, while the governor, who controlled political appointments, played favorites with his wealthy friends.

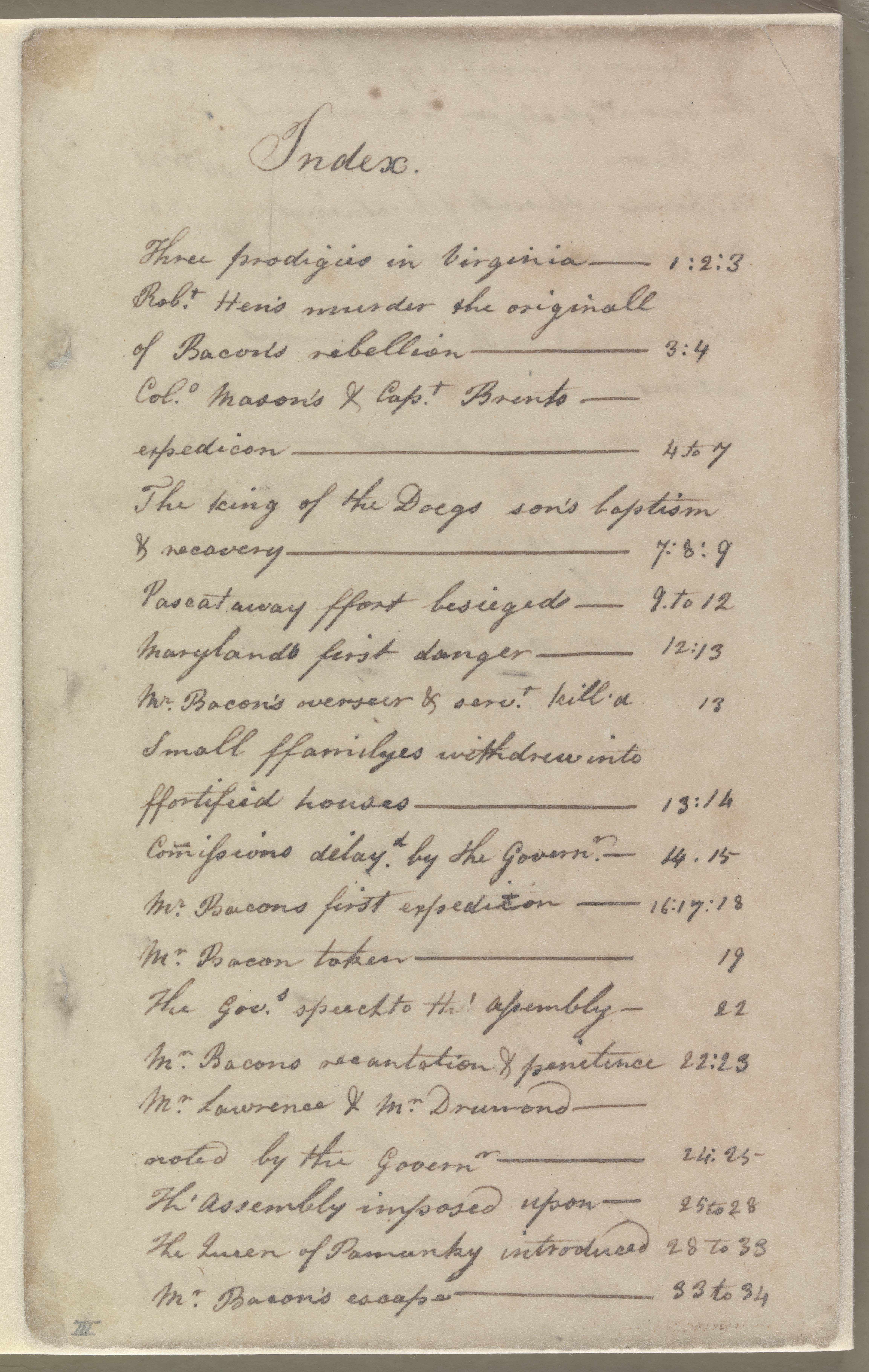

Colonists on the frontier also felt threatened by the Indians, in whom they found a scapegoat for their troubles. Many settlers wanted the Indians to be driven out of their land or be killed. Former servants believed that acquiring available land required taking it from the Indians. Governor Berkeley, on the other hand, wanted accommodation of friendly tribes. Within this context, a dispute near the Potomac River in the Northern Neck in July 1675 triggered the series of events that led to the uprising. A quarrel between merchant-planter Thomas Mathew and the Doeg Indians provoked their attempt to steal livestock from Matthew’s farm, to which Mathew responded by killing several of them. The Virginia militia led a retaliatory raid that mistakenly attacked the friendly Susquehannocks, instigating more Indian raids on the frontier. Disagreement ensued over how to handle the outbreak of violence. Into this volatile situation stepped Nathaniel Bacon.

Bacon, a cousin of Berkeley’s by marriage, had only recently arrived in Virginia. Unlike most of his followers, he was socially and politically prominent. Upon arriving in 1675, Berkeley gave him a land grant and a seat on the Governor’s Council. His father had sent him to Virginia with an abundance of silver after he was accused of trying to cheat a neighbor out of his inheritance. Pitted against this troublemaker was Berkeley, who was viewed as incompetent and corrupt. While the conflict cannot be reduced to the characters of these two men, their personalities do reveal much about the dramatic unfolding of events.

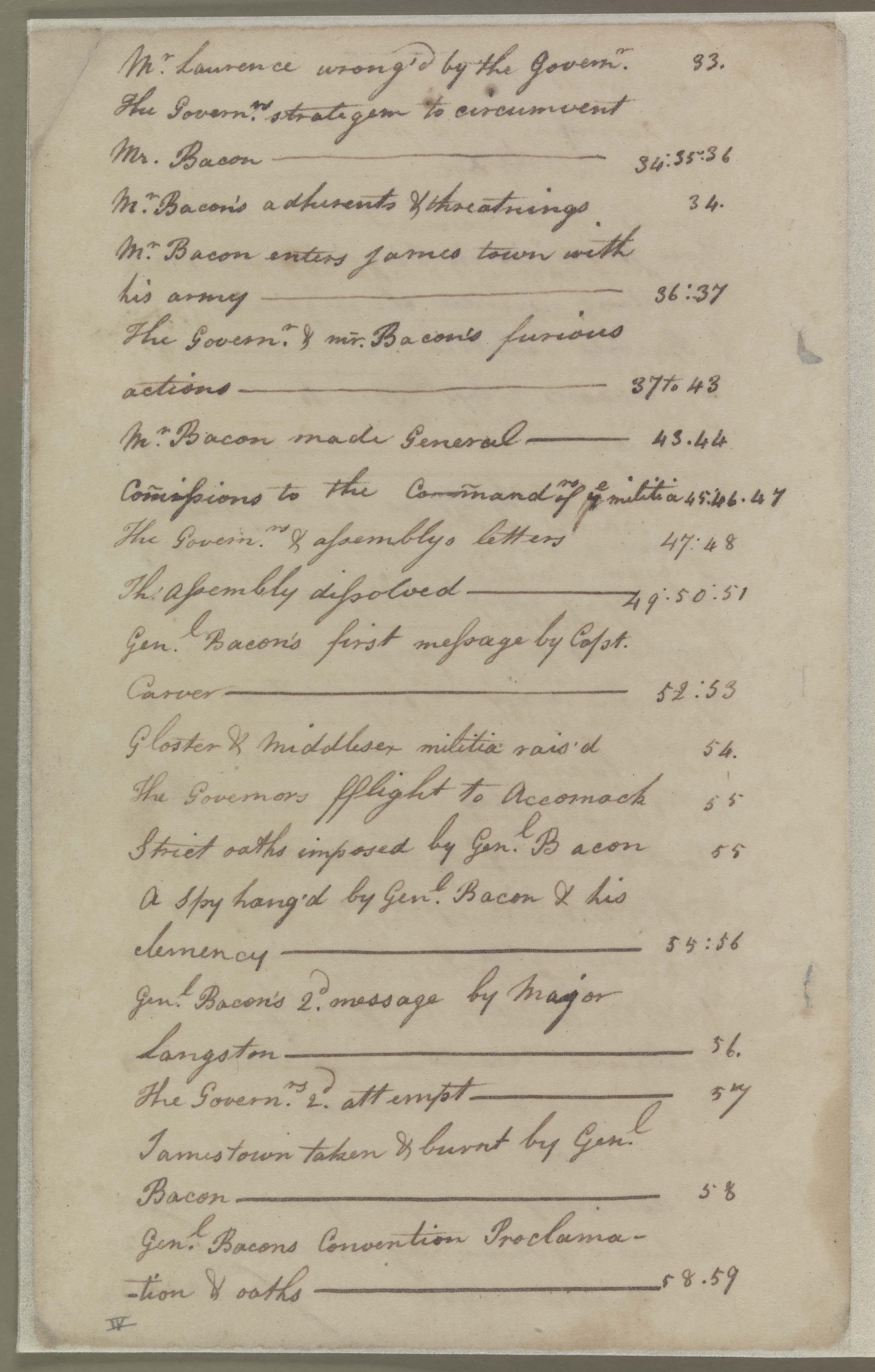

Determining how best to fight the Indians created division within the House of Burgesses. Berkeley had attempted to find a compromise between retaining the friendship of loyal subject tribes while easing colonists’ fears. In March 1676, the General Assembly declared war on hostile Indians and planned to erect defensive fortifications paid for by taxes that poor settlers found unfair and burdensome. Additionally, the Assembly established rules for trading with friendly tribes, effectively restricting trade to friends of Berkeley’s. Bacon, who wanted more aggressive action, took command of a volunteer militia and demanded a commission from the governor to fight the Indians, which Berkeley denied. Bacon proceeded to raid, loot, and kill, despite Berkeley’s refusal to recognize his vigilante group.

Berkeley declared Bacon a rebel and removed him from the Council, while promising him a fair trial and offering to pardon his supporters, but Bacon refused to surrender. Though publicly deemed an outlaw, he was elected a burgess from Henrico County by sympathetic landowners. By this point, he had militant control over much of the colony, and his armed retainer may have won votes through intimidation.

Arriving at Jamestown in June, Bacon was captured and forced to capitulate before taking his seat in the assembly. He once again demanded his commission, was denied, expelled from the council a second time, and returned later to surround the statehouse with a volunteer army. During the dramatic showdown, Berkeley dared Bacon to shoot him, although the governor ultimately capitulated, agreeing to Bacon’s demands and pardoning him of all offenses. With the governor’s loss of control, the Indian war became a civil war.

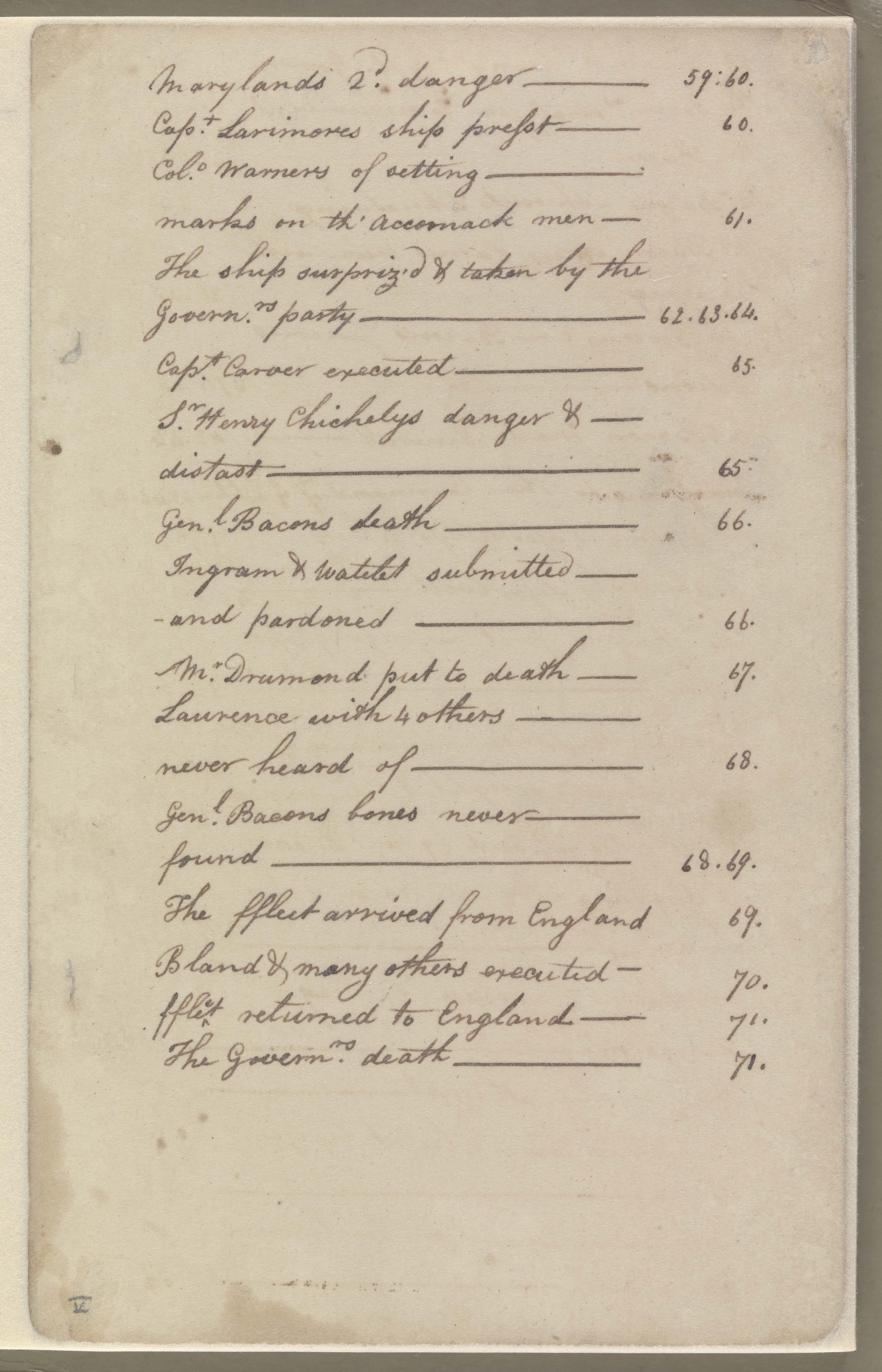

On July 30, 1676, Bacon issued a “Declaration in the Name of the People”, which he signed “Generall, by the consent of the People.” His declaration was directed against Berkeley and the governing elite, whom he charged were corrupt and negligent. They had issued “great unjust taxes upon the Comonality for the advancement of private favourites and other sinister ends,” and “protected, favoured and Imboldened the Indians against his Majesties loyall subjects, never contriveing, requireing or appointing any due or proper meanes of satisfaction for theire many Invasions, robberies, and murthers committeed upon us.” Bacon continued his military campaigns while Berkeley tried to retake Jamestown. Bacon laid siege to the town, forcing Berkeley to flee again. Determining he could neither hold the capital or risk losing it again, Bacon burned Jamestown on September 19. The fire destroyed many houses, the church, and the statehouse.

On October 26, Bacon died abruptly of dysentery and his body was never found. The following day, King Charles II issued a royal proclamation to put down the rebellion, sending a fleet to Virginia and commissioners to investigate the cause. The fighting continued for several months before Berkeley regained control. He hanged twenty-three leaders of the rebellion. The commissioners accused him of excessive harshness in punishing rebels and seizing property without due process, which he allegedly used to enrich himself. They removed Berkeley as governor, and he returned to England intending to defend himself before Charles II. He was in poor health, however, and died in July of 1677, without ever having the chance to tell his version of events.

For over a century, Bacon’s Rebellion was viewed as a precursor to Revolutionary War. However, the discontent for the governing authority in the former rebellion stemmed more from economic, social, and political stratification within the colony than a direct response to English legislation. And while his primary enemy was Berkeley and his cronies, Bacon found an equal if not greater foe in the Indians. The Indians had been subjugated, and Berkeley and the elites no longer saw them as a threat. However, frontiersmen did not feel the same security as did older planters in eastern Virginia.

Bacon’s aim was to seize Indian land, and the crisis was blamed on Berkeley’s refusal to sanction this fight. Yet hostility toward the Indians was tied to systemic grievances felt by a large segment of the population. Small western planters who were most affected by raids and high taxes sided with Bacon, as did indentured and former servants and slaves. Indentured servants became an increasingly less reliable workforce as demand for labor grew and servant migration waned. The gentry viewed a surplus of landless former servants as dangerous, as Berkeley wrote, “How miserable that man is that Governs a People when six parts of Seaven at least are Poor Endebted Discontented and Armed.” The shift from servant to slave labor accelerated once the slave trade made African slaves available in large numbers. Planters saw the benefit of slavery as lifelong and as a status of birth, which satisfied a continuous labor supply.

Bacon’s Rebellion failed to overturn the established order in the colony. In fact, after the rebellion, the planter elite consolidated power, and intensified the social inequalities that would characterize 18th century Virginia. It did advance substantial demographic change, however. The population of African slaves multiplied, while that of white immigrants slowed. Racial unity between poor and wealthy whites was defined as the slave population grew, and racial distinctions became interwoven into the laws and social fabric of the colony.

Archival Context:

The beginning, progress and conclusion of Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia in the years 1675 & 1676, written in 1705, is a first-hand narrative account of Bacon’s Rebellion. The author, “T.M.,” is Thomas Mathew of Northumberland County, whose quarrel with the Doeg Indians in 1675 historians have attributed as the first in a series of disruptive incidents that led to the uprising. Dissent in the House of Burgesses over how to peacefully resolve this dispute prompted Bacon’s revolt.

The manuscript is addressed to Robert Harley, Lord Oxford, Minister of State to Queen Anne, and is believed to have been a part of his private library and written at his request. Although the collection of Harleian manuscripts was sold to the British Museum in 1753, this document was traded or sold elsewhere. In November 1801, American diplomat Rufus King bought the manuscript from a London bookseller. He sent it to President Thomas Jefferson in December 1803. Jefferson made a copy of the manuscript, which is now in the Library of Congress. A contemporary copy made from Jefferson’s manuscript is in the library of the Virginia Museum of History & Culture. It belonged at one point to Presbyterian minister John Holt Rice and was bequeathed to the Virginia Historical Society by Nathan Pollard in 1834.

The Source:

The beginning, progress and conclusion of Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia in the years 1675 & 1676 was written thirty years after the event. In the preface, Mathew informs Lord Oxford that he wanted to present the facts with accuracy, but notes that the lapse of thirty years led to inevitable shortcomings in recollection: “Beseeching yo'r hono'r will vouchsafe to allow, that in 30 years, divers occurrances are laps'd out of mind, and others imperfectly retained.” Despite drawing from memory and hearsay, Mathew was well-suited to write the narrative, having been an eye-witness to many of the events he describes.

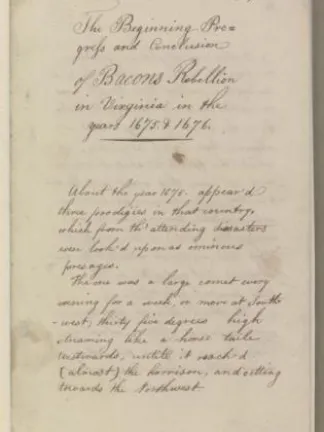

Mathew owned extensive land in Virginia. He was a county justice in Northumberland County, and served as a burgess in 1676 representing Stafford County. However, he remained outside the political infighting and twice refused an offer from Bacon to be made a lieutenant in his militia. While Mathew may have steered clear of taking sides in the Assembly, his narrative clearly places blame for the rebellion on the Indians. He begins his story by dramatically recalling ominous signs in 1675 that trouble was brewing:

“The one was a large comet every evening for a week…Another was, fflights of pigeons in breadth nigh a quarter of the midhemisphere…this sight put the old planters under the more portentous apprehensions, because the like was seen (as they said) in the year 1640 when th' Indians committed the last massacre... but not after, until that present year 1675. The third strange appearance was swarms of fflyes about an inch long… and in a month left us.”

He links these superstitions to the event that started the war:

“My dwelling was in Northumberland, the lowest county on Potomack river, Stafford being the upmost, where having also a plantation, servants, cattle &c, my overseer there had agreed with one Robt. Hen to come thither, and be my herdsman, who then lived ten miles above it; but on a Sabbath day morning in the sumer anno 1675. people in their way to church, saw this Hen lying thwart his threshold, and an Indian without the door, both chopt on their heads, arms and other parts, as if done with Indian hatchetts, th' Indian was dead, but Hen when ask'd who did that? answered Doegs Doegs, and soon died, then a boy came out from under a bed, where he had hid himself, and told them, Indians had come at break of day and done those murders.”

Not only were the Indians a threat to the colonists’ safety, but their sorcery had created a summer of drought.

Mathew’s story struck a chord with President Jefferson. After reading the manuscript, Jefferson believed that Bacon and his followers were motivated by no less than self-preservation, and that the blame for the rebellion rested on Berkeley. Jefferson saw Mathew’s manuscript as proof that Bacon was a patriot whose actions were yet another example that “insurrections proceed oftener from the misconduct of those in power than from the factious and turbulent temper of the people.” Given Jefferson’s role in the Revolution, it is not difficult to understand why he held this opinion. However, the causes of the 1676 rebellion were not a cut and dry as Mathew, and Jefferson after him, believed.

Transcripts:

Suggested Reading:

- “The Beginning, Progress, and Conclusion of Bacon’s Rebellion, 1675-1676, [1705],” in Narratives of the Insurrections, 1675-1690. Edited by Charles M. Andrews. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915.

- Learn about Bacon's Epitaph.