When we talk about “Christmas in the trenches,” it is easy to imagine troops hunkered down in bunkers, eating tasteless rations out of mess kits, tired, dirty, cold, and longing for home. But that was not always the case. Several items in the VMHC collections illustrate that Christmas was not always a time of great physical suffering, although being away from friends and family was a hardship.

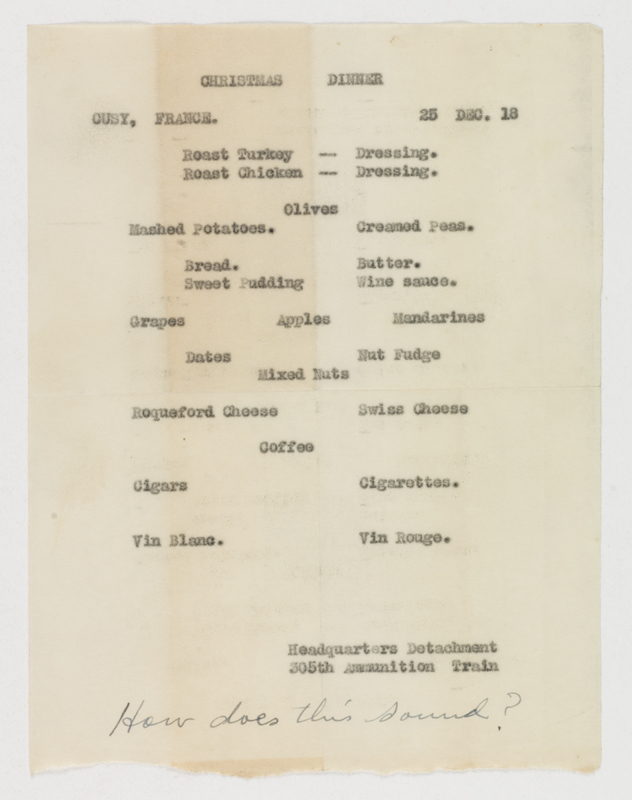

Philip “Clayton” Holladay was in the Burgundy region of north-central France on Christmas Day 1918. He was serving with the Headquarters Detachment of the 305th Ammunition Train of the American Expeditionary Forces. His letter home to his parents in Richmond gives the highlights of the menu for the upcoming Christmas Dinner. Thanks to the efforts of Clayton and his first sergeant, the troops would enjoy chicken, turkey, and veal. The typewritten menu, which he encloses in a later letter, is a bit more elaborate. It includes the aforementioned turkey and chicken, as well as olives, mashed potatoes, creamed peas, sweet pudding with wine sauce, grapes, apples, mandarins [oranges], dates, nuts, and Roqueford [sic] Cheese and ends with coffee, cigars, and cigarettes. There is, of course, both white and red wine. In contrast to this delightful repast, he mentions that “It really doesn’t seem at all like Christmas—being so far from home, raining, and these French people are all so poor and anyhow make nothing of Christmas.”