Food and dining were integral to social life in the eighteenth century, particularly among the upper class. The gentry demonstrated their wealth and status through the table spread, and multi-course meals could last hours. The most valued cooks in the colony were formally trained in Europe and worked for the royal governor. These “principal cooks” prepared cuisine with a distinctive French influence that was popular in England at the time. Gentry cooks were highly skilled and prized slaves who prepared more traditional English dishes. Unlike the cuisine of the elites, the diets of the middle and lower classes were not extravagant. Though middle class Virginians often followed the entertaining style of the gentry, they often relied on the mistress of the house to cook, and their meals were far less refined and varied, while poor households served one-pot meals.

Cookbooks and kitchen inventories provide the most detail about food and dining practices among the gentry. Many ingredients in colonial cooking are similar those used today, including meats, fish, vegetables, baked goods, coffee, tea, and chocolate. However, tastes, customs, and practical limitations dictated very different cooking methods and expectations. Fresh fruits and vegetables were not available year-round, and were never eaten raw. Meats could survive long-term preservation from salting or smoking, but could not last short-term. Meat dishes were served at dinner, the largest meal of the day, which took place mid-afternoon, and the leftovers were consumed at supper and breakfast the following day. The gentry diet was heavy on greasy meats, light on bread, and liberal in spices and sweeteners, including sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Sweet wines and alcoholic punches were preferred to dry wine and alcohol-infused desserts were common.

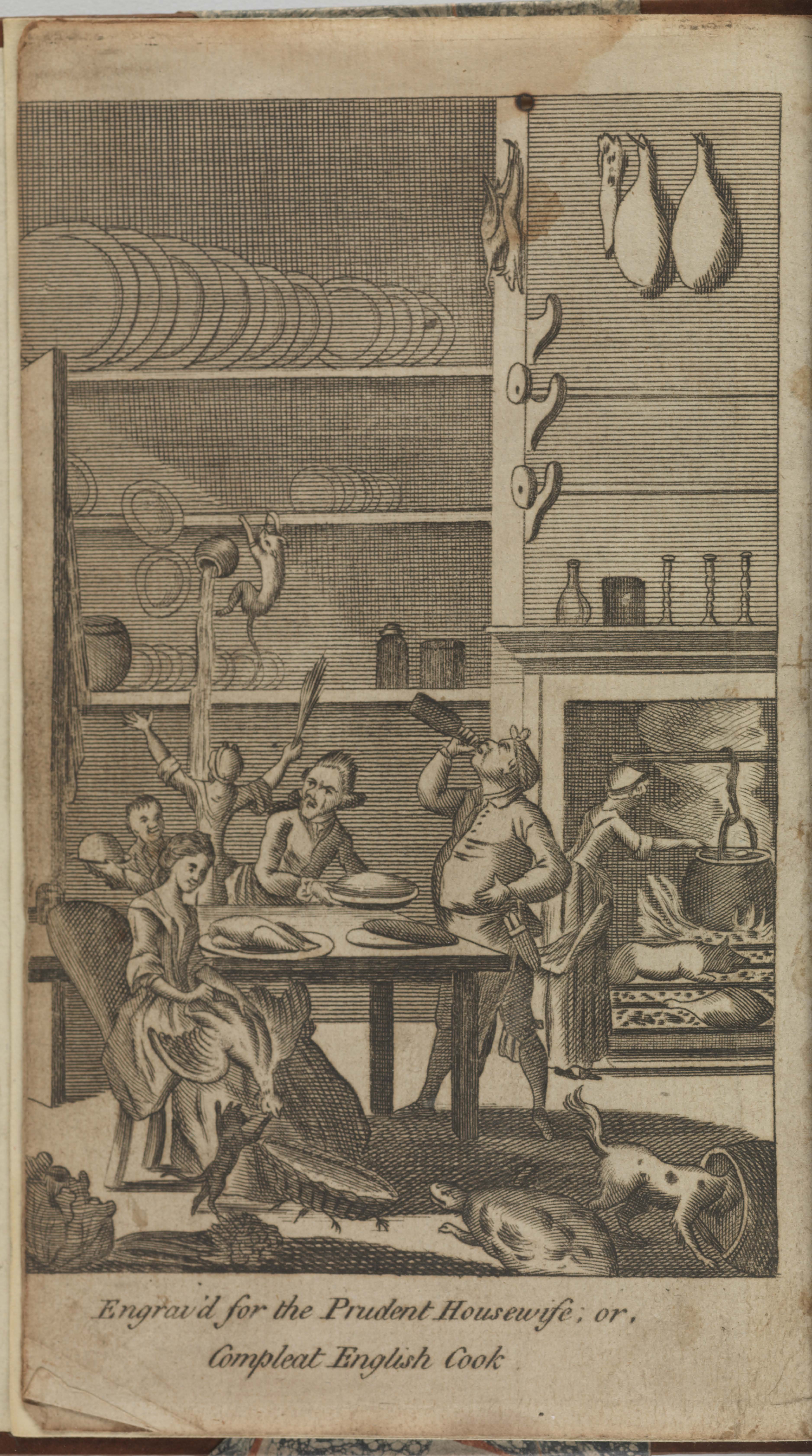

As dining was an elaborate ritual for elites, food preparation required a great amount of work. Though slaves performed most of the cooking, mistresses of prominent households rationed food to their cooks and planned meals. With help from slaves, gentry women cared for their own gardens and supervised work in kitchens, dairies, smokehouses, and butchery. The vast material wealth acquired by the eighteenth century awarded greater comfort to gentry women, but also demanded more labor and oversight, especially in preparing extravagant ritual feasts.

Creating daily menus and managing food preparation left little time for leisure. And as prominent households acquired more slaves, matrons had more tasks to manage. Besides administering the daily operations of the estate, gentry women cared for their luxury items, such as fine silks, carpets, and silver, raised their children with help from slaves, and provided medical care to their expanding families and laborers. Gentry daughters, meanwhile, spent their time reading, sewing, playing music, and socializing, while their brothers received a formal education.

Women on small farms performed much of the same work as did slaves of the gentry, but on a smaller scale. They spun wool, cooked, and cleaned. Urban women made hats and dresses, served as midwives, and some as “doctoresses,” though medical work typically was considered a duty rather than a profession. Wives of craftsmen often learned specialized skills from their husbands and could work from home while attending to their children and other responsibilities. Although the range and scope of women’s chores varied along social and economic lines, women in colonial Virginia shared many common tasks that involved preparing and cooking food, running households, and providing medical care both within and outside the home. Cookbooks became valuable guides to fulfilling domestic and social obligations and reveal the necessary role of women in the social makeup and daily progression of colonial life.

THE PRUDENT HOUSEWIFE: OR, COMPLETE ENGLISH COOK FOR TOWN AND COUNTRY

In 1750, The Prudent Housewife: or, Complete English Cook for Town and Country was published. Colonial cookbooks contained more than just food recipes? They included home remedies for medical problems, as well as instructions on how to manage households and navigate daily chores. Cookbooks were passed to friends and daughters, transmitting culinary and housekeeping techniques and customs through generations of women. They are valuable sources of social history, revealing much about the dining practices and lifestyles that helped create a distinct cuisine and culture in eighteenth-century Virginia.