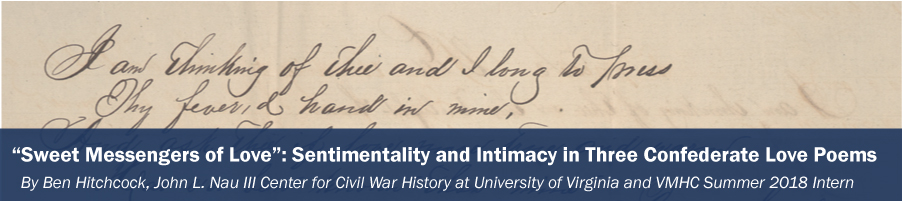

The most prominent Civil War poetry is poetry of the battlefield. The war has been immortalized in countless sweeping odes about fallen soldiers and righteous bloodshed. Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle-Hymn of the Republic” sings of “fiery gospel,” blaring trumpets, a “terrible swift sword.” Walt Whitman’s famous elegy for Abraham Lincoln, “O Captain! My Captain!”, juxtaposes lurid “bleeding drops of red” with trilling bugles and exulting masses. Often called the Poet Laureate of the Confederacy, Henry Timrod compared the creation of the Confederate States of America to a new star appearing in the night sky, called the oncoming war a “rapturous sight,” and believed that God would make the new country “great and rich.” This is poetry meant to stir the blood of soldiers and civilians alike, meant to inspire action and sentiment on a grand scale.

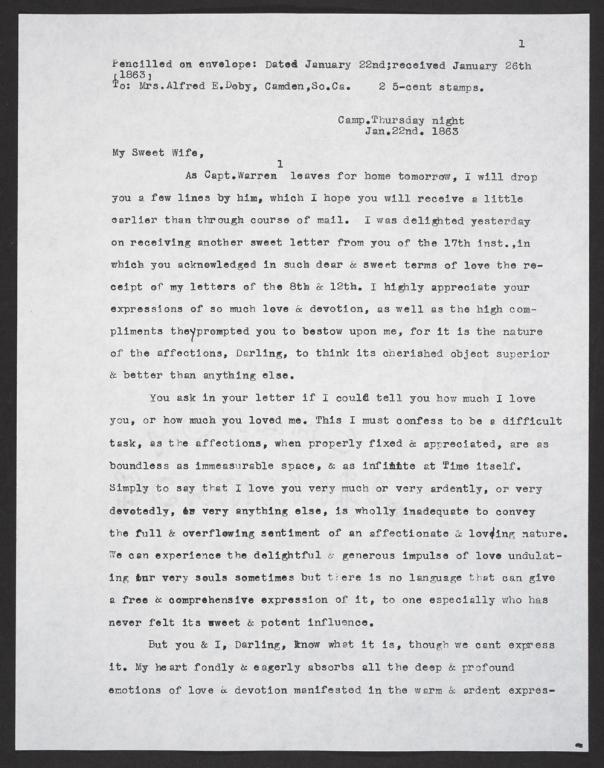

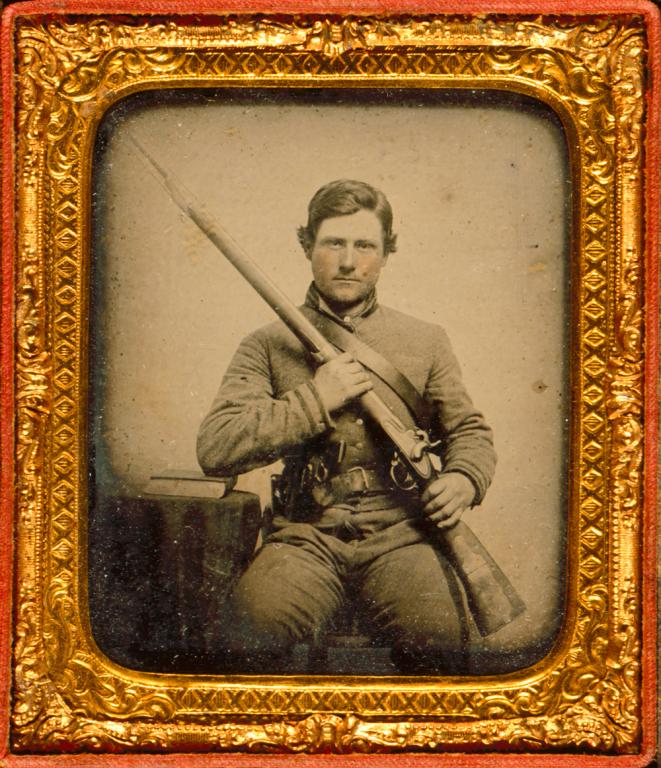

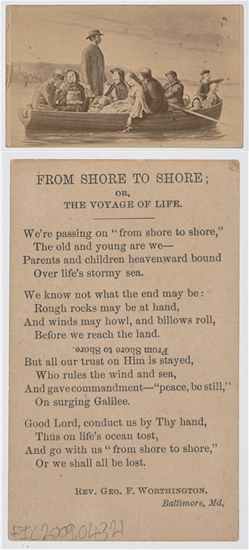

Not all poetry written during the war had such lofty aims, however. The soldiers’ letters found in the Confederate Memorial Literary Society Manuscript Collections (CMLS) managed by the Virginia Museum of History and Culture are full of intimate, personal love poems written by soldiers to their wives, families, and love interests on the home front. Soldiers’ love poems lack the grandiose pronouncements and political rhetoric of Howe, Whitman, and Timrod. Nevertheless, the poems have much to say about the experience of soldiering and the literary culture of the 19th century.

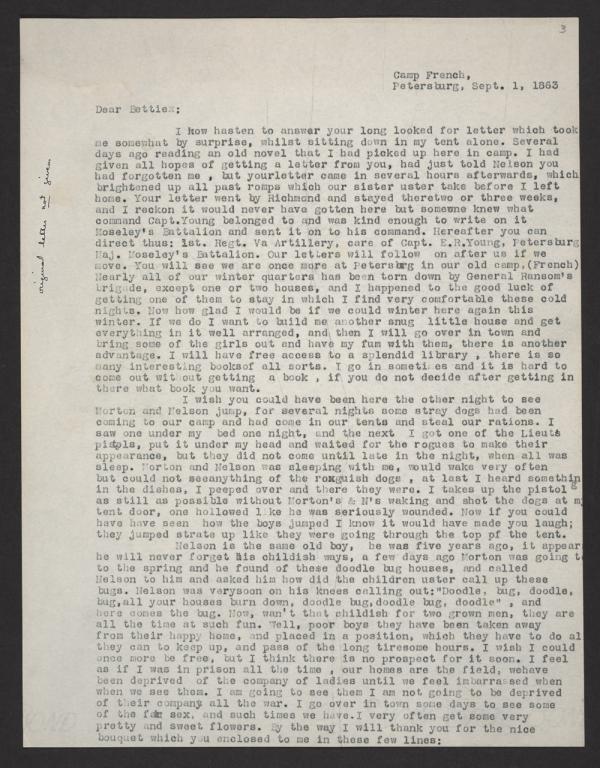

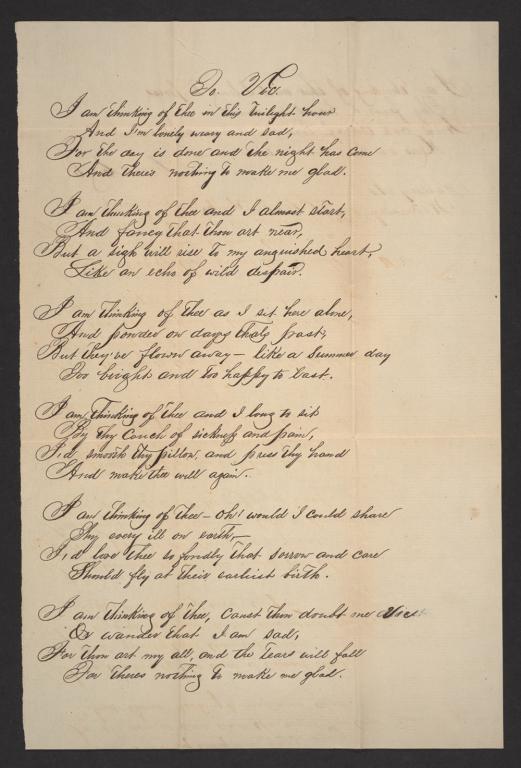

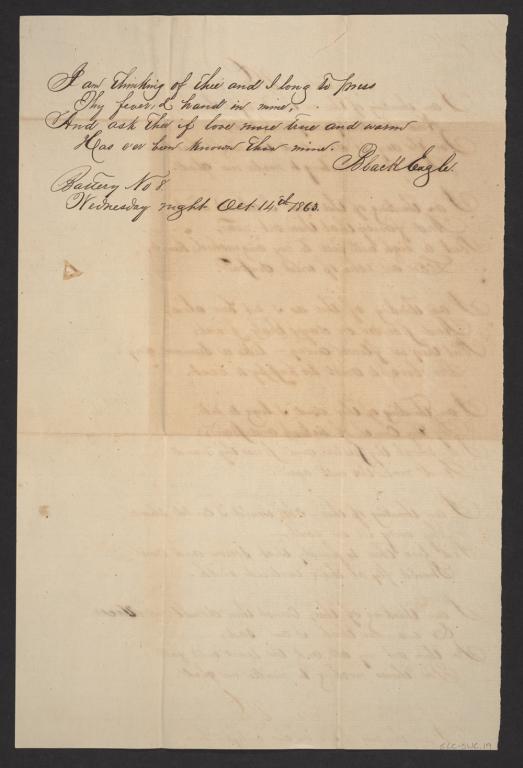

Three exceptional love poems from Confederate soldiers have recently been added to the archives of the VMHC. Click on the image of each letter to see it in an expanded view and click on the “i” icon to more clearly read each letter’s text.