Leon Maurice Nelson Bazile was a lawyer, legislator, and judge of Virginia's Fifteenth Judicial Circuit from 1941–1965. A native and lifelong resident of Hanover County, Bazile was also a student of local history, especially that of St. Martin's Parish, the western-most section of the county. Bazile’s name may be familiar to you: He was the judge who sentenced Mildred and Richard Loving each to a year in prison for violating the state’s ban on interracial marriage and suspended the sentences when the couple agreed to leave the state. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Bazile’s decision in the landmark ruling, Loving v. Virginia.

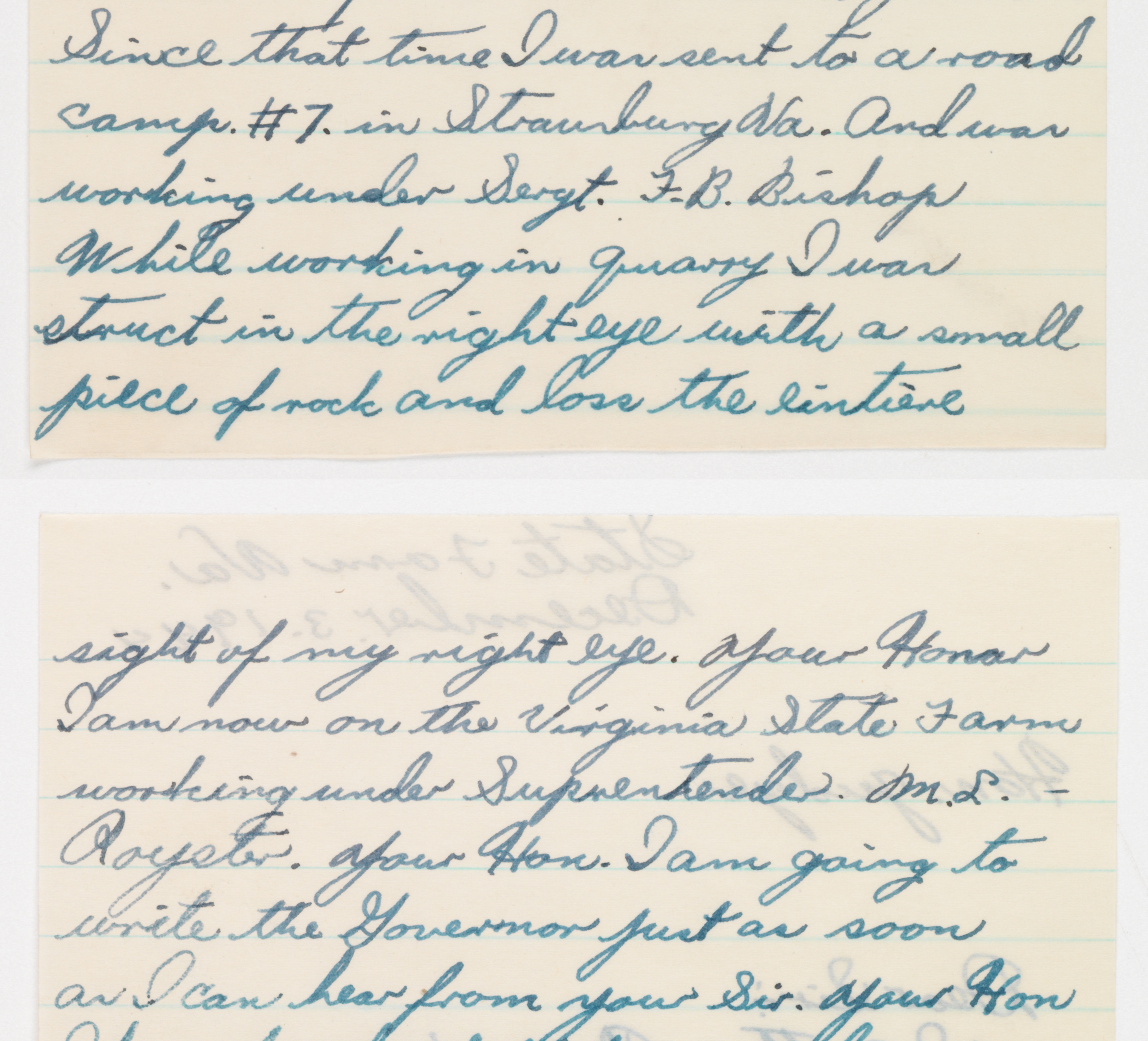

While the Leon M. (Leon Maurice) Bazile Papers, 1826–1967, a collection in the VMHC archives, includes very little documentation of the Loving v. Virginia case, it does contain dozens of letters written to Bazile by inmates who had been convicted in his court. Most often, these letters contained pleas for reductions in sentence and support for pardons. Many were sent from the state prison on Spring Street and the state farm in Goochland, but others were written from the state’s convict road camps. At these camps, state and local prisoners worked on the highways. In an excerpt from one such letter, Arthur Page requests a conditional pardon because of an injury he received working on the roads:

“I was sent to a road camp #7 in Strausburg Va. And was working under Sergt. F. B. Bishop While working in the quarry I was struck in the right eye with a small piece of rock and loss the entire sight of my right eye.”

For much of the twentieth century, convicts worked on Virginia’s roads. This practice grew out of the convict lease system that began right after the Civil War. Virginia and other southern states leased convicts for profit. Most were African American. Virginia provided convicts to railroads, quarries, and the James River and Kanawha Canal Company. The practice served several purposes—raising revenue, alleviating overcrowding in jails, and controlling a newly emancipated black population. Leased convicts often faced hardships and cruel treatment. An 1881 report claimed that the death rate in the convict camps of the Richmond and Allegheny Railroad was seven times higher than the death rate for inmates inside the penitentiary.

Nonetheless, historian Matthew J. Mancini, author of One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South,1866–1928, cites Virginia as an exception to the rule. Many Virginians opposed convict leasing, and the practice began to taper off in the 1890s. In 1906, however, the General Assembly established the State Highway Commission and set up a system of convict road camps operated jointly by the commission and the penitentiary. Convict roadwork became the last vestige of the lease system.

This was not the case in most other southern states. Unlike Virginia, many former Confederate states had no prisons at the close of the Civil War. Determined to maintain control over a large free black population, they coerced thousands of innocent men and women into forced labor between the 1870s and 1940s. Many were charged with offenses such as vagrancy, brought before a county judge and fined. When they could not pay the fine and court fees, a sentence was determined and the convicts leased out to turpentine camps, coal mines, and railroads as well as to individual farms.

Bill Obrochta is the manager of educational services at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture.