On October 16, 1859, John Brown led eighteen followers in a raid on the federal arsenal and armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown planned to use the weapons seized to arm slaves and initiate a general uprising. No one rallied to Brown’s banner, however, and the insurrection collapsed. On October 18, a detachment of marines under Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee attacked the engine house of the armory where the raiders held a handful of hostages. Most of Brown’s men were killed in the attack, and he was wounded. Captured and arrested for treason, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. On December 2, 1859, John Brown was hanged in Charlestown, Virginia.

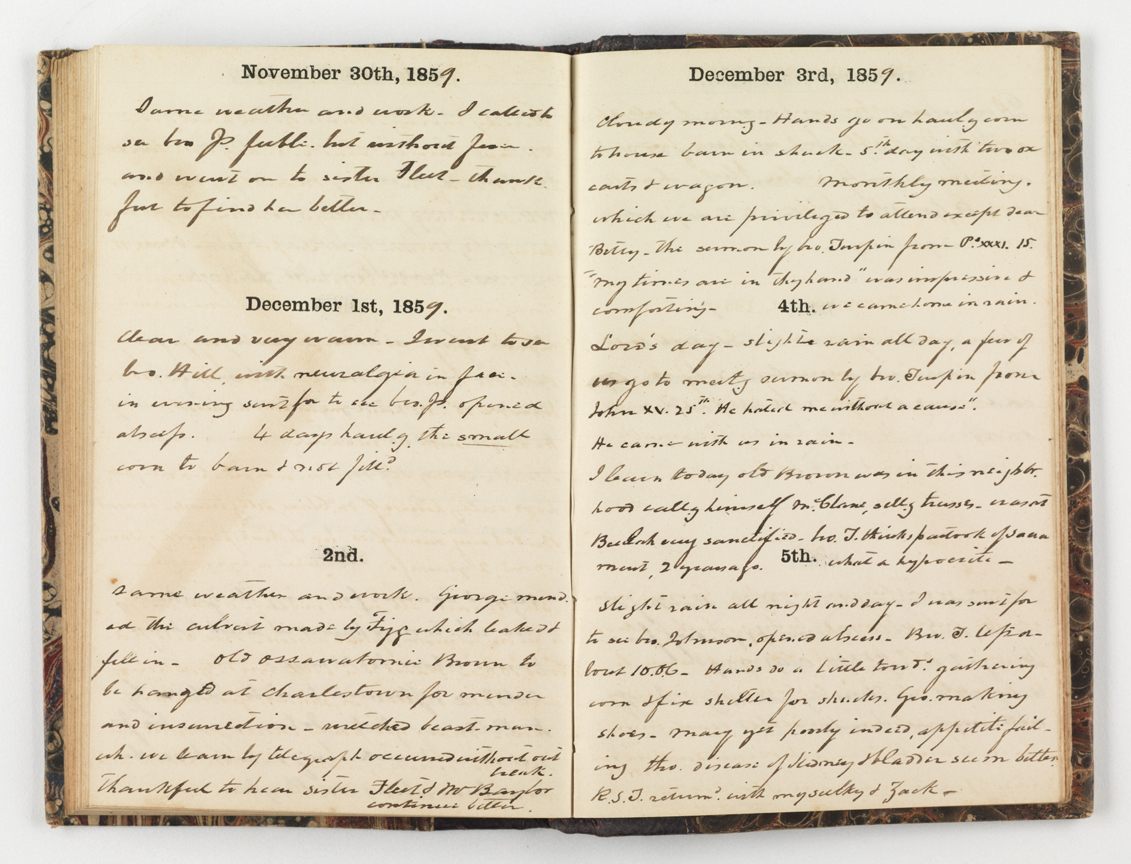

The event did not go unnoticed by William Gwathmey, a King William County planter and physician. Like many farmers he kept a diary, recording details about the weather, farming operations, physician’s visits, and activities at the Beulah Baptist Church. Only occasionally did national events intrude on his daily routine. However, on the date of Brown’s execution, Gwathmey wrote, “old ossawatomie Brown to be hanged at Charlestown for murder and insurrection—wicked beast[ly] man.” Gwathmey’s diary entries on this and subsequent days give us a glimpse into the fear, anger, and confusion of a white Virginia planter in response to the Harpers Ferry raid.