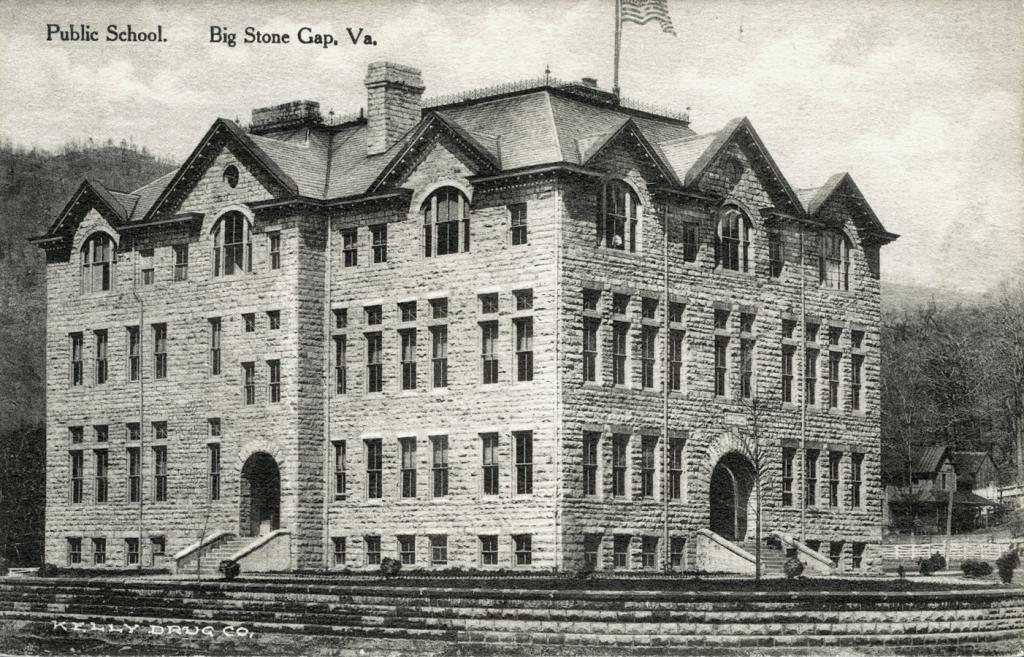

The Virginia Constitution of 1869, passed during Reconstruction, established a statewide system of free public schools. Despite this, public education during the nineteenth century more closely resembled its pre–Civil War predecessors than today's system.

The Virginia Constitution of 1869, passed during Reconstruction, established a statewide system of free public schools. Despite this, public education during the nineteenth century more closely resembled its pre–Civil War predecessors than today's system. Education was decentralized and unsystematic. There were no compulsory attendance laws, no standards for teachers, no required curriculum, and no uniform length of terms. Schools in the city were very different from those in rural areas. For example, in 1888, Amherst County schools were open for an average of ninety-eight days, while schools across the James River in Lynchburg were open for 193 days. Throughout the state, but especially in rural areas, attendance was haphazard. In Buckingham County in 1889, only 51 percent of white school-aged children and 35 percent of black school-aged children were enrolled in school. Average daily attendance was even smaller—31 percent of white children and only one in five black children. This was fairly typical in rural areas.

A good deal of teacher energy was directed at attracting and maintaining students. If average daily attendance fell below a certain level, usually about twenty, the local superintendent saw this as an indication of declining support and teacher salaries were cut proportionally. If the decline continued, a teacher's contract was not renewed. The usual measure of a teacher's effectiveness was his or her ability to discipline the students, especially the older boys. In one instance, the Prince William County school board balked at hiring a prospective fourteen-year-old teacher because of doubts about her ability to control students who had been her classmates the year before.