Valentine’s Day cards and the celebrations around the holiday began to escalate during the early twentieth century. Yet, there is one twentieth-century woman who did not receive a valentine from a man to whom she was secretly engaged from 1917 to 1918. Ellen Glasgow (1874-1945) was forty-three and an acclaimed Richmond novelist when she first met Henry Watkins Anderson on Easter Sunday 1916 after the death of her father. In her autobiography, The Woman Within, published after her death, Glasgow writes that “I was surprised by the attraction of opposites . . . for my part, I was warmed and thrilled by the man’s vitality” (p. 225).

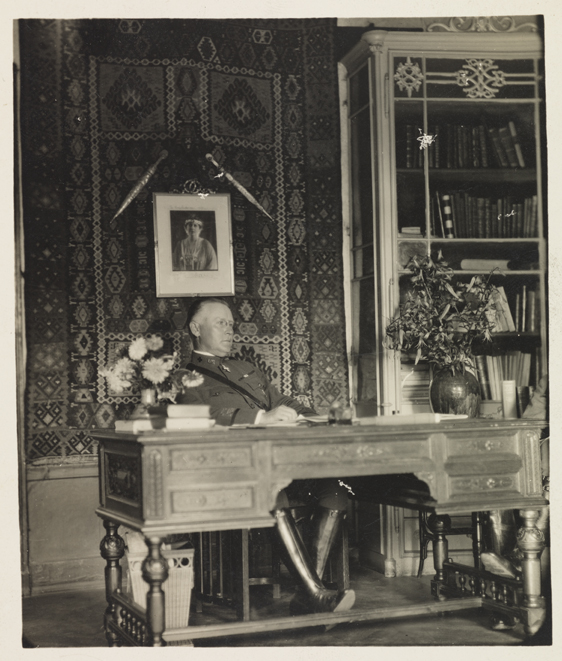

Henry Watkins Anderson was a Richmond corporate attorney who became an ardent supporter of the Red Cross after the United States entered World War I. Given the rank of colonel by the Red Cross, he was appointed its commissioner to the Balkans.