Revolution at Sea

On March 8, 1862, the world's first ironclad ship, CSS Virginia, destroyed two wooden-hulled U.S. warships at Hampton Roads. A Virginia-born sailor on the USS Cumberland observed, "None of our shots did appear to have an effect on her." This battle revolutionized naval warfare by proving that wooden vessels were obsolete against ironclads.

The next day the Union’s first ironclad—the USS Monitor—arrived and fought the Virginia to a draw, ensuring the safety of the Union blockade fleet. A Union sailor from Staunton remarked that "John Bull [Great Britain] will have to build a new navy." Within weeks, Great Britain—the world’s leading naval power—canceled construction of wooden ships.

Constructed on the salvaged hull of the captured USS Merrimack, the first Confederate ironclad was rechristened the CSS Virginia. Artist Xanthus Smith and the northern press, however, rejected that name in favor of the alliteration of Monitor and Merrimack.

War Rides the Rails

For thousands of years, every army that went into battle did so by the power of men and animals carrying it across the countryside. By 1860, however, 30,626 miles of railroad track spread across the United States—1,771 of these in Virginia.

Locomotives traveled five times as fast as mule-drawn wagons, transported soldiers close to the scene of battle without tiring them, and allowed armies to operate farther from their bases of supply.

The strategic importance of railroads tended to channel offensive operations along the routes of railroad lines. Railroad centers—such as Grafton, Manassas, Petersburg, Charlottesville, Lynchburg, and Wytheville—became important military objectives.

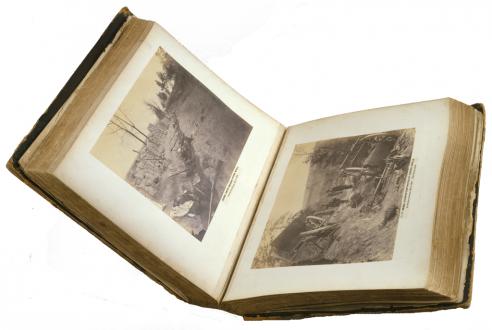

Throughout the war, Confederate forces in Virginia slowed United States troop movements by destroying wooden bridges that spanned Virginia’s countless rivers and streams. The artist, Alfred Wordsworth Thompson, noted: “The destruction of Locomotives on the Baltimore & Ohio R. Road has been terrible; no less than 50 of the finest kind having been burnt or broken up, at Martinsburg & other points on the Road."