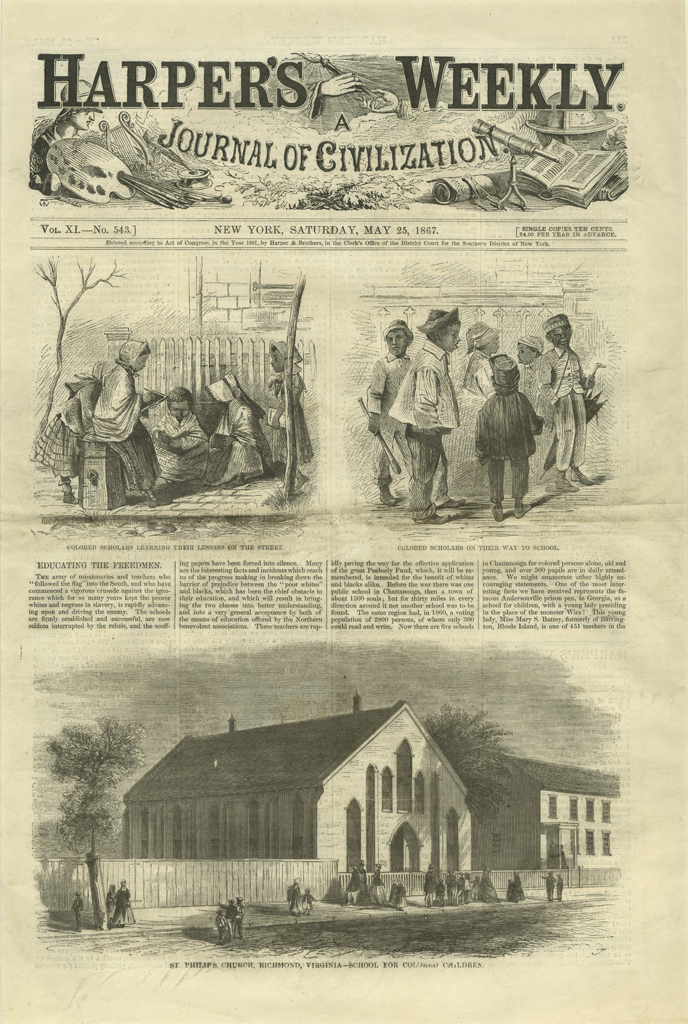

In the antebellum South, Black people generally were prevented from receiving a formal education. In many places it was illegal even to teach a Black person to read and write, although such laws often were not enforced—and many Black people became literate. During the Civil War, northern missionaries and Black teachers established schools in Union-occupied territories. After Appomattox, freedpeople—adults and children alike—flocked to newly founded schools. Attaining an education was both a symbolic step away from slavery and a practical goal: Black southerners valued the ability to understand labor contracts and other legal documents.

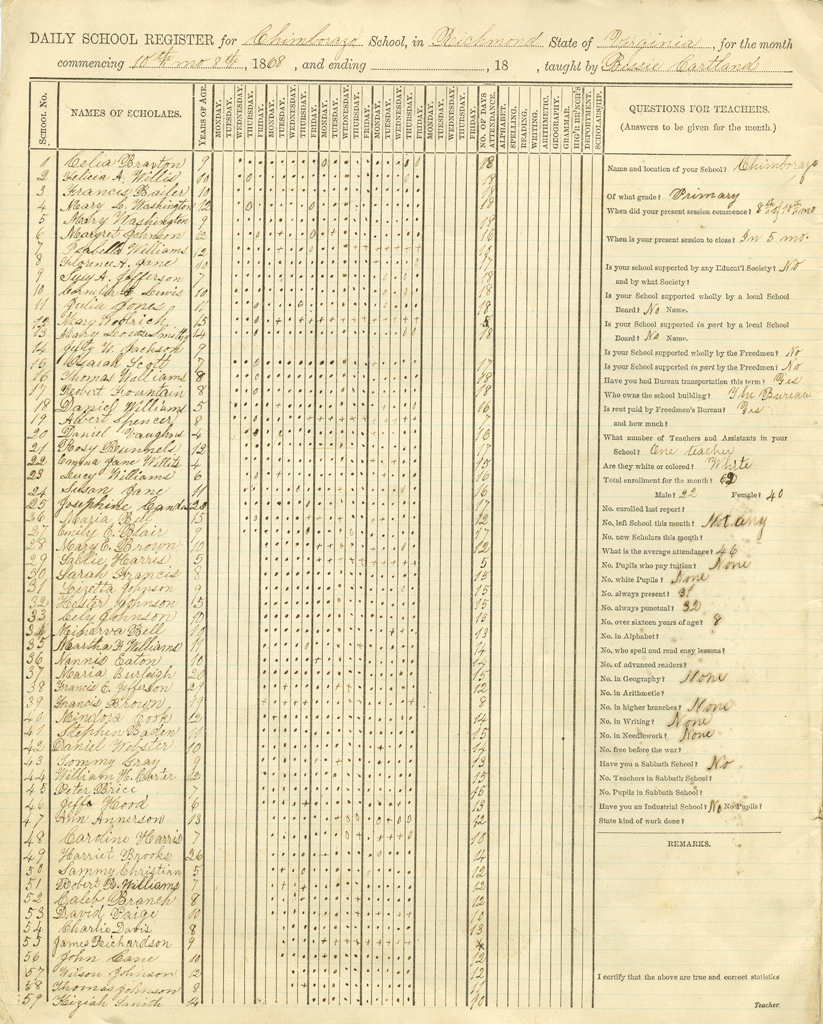

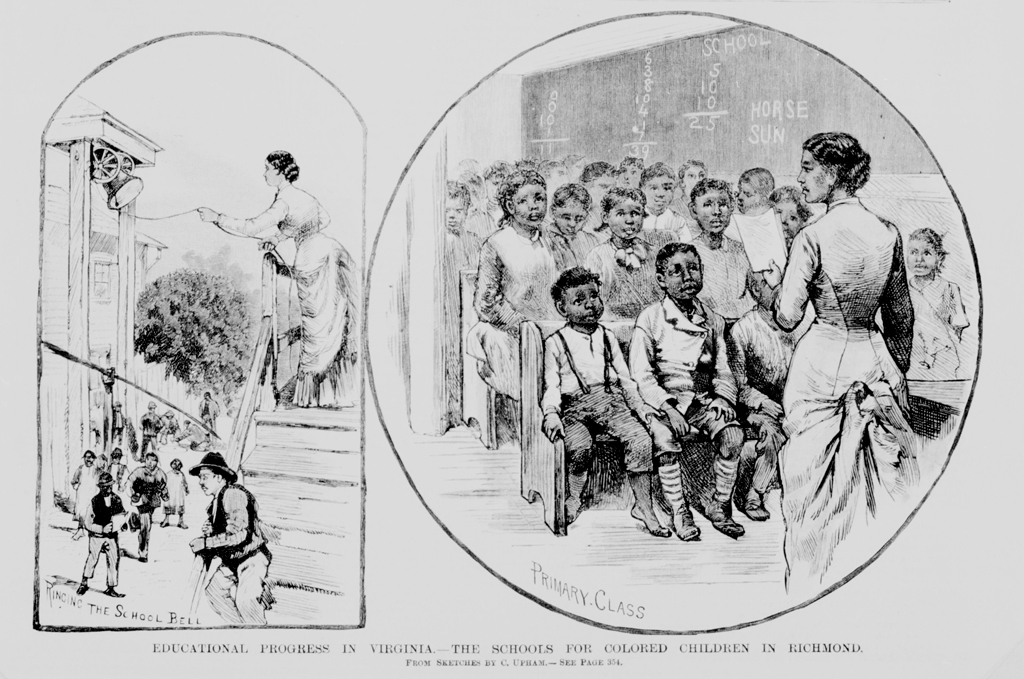

In Richmond, one of the earliest Black schools was established in the eastern end of the city at Chimborazo in June 1865, on the site where the large Confederate hospital had operated just a few weeks before. During the Reconstruction period the federal Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (commonly called the Freedmen's Bureau) used its authority over former Confederate properties to provide buildings for Black schools. The Freedmen's Bureau, missionary associations, and southern Black communities funded the schools; many of the mostly white, female teachers from the North were sponsored by missionary groups. The New York Friends' Association supported the Chimborazo School, which had enrolled over three hundred students by November 1865. The register for October 1868 reflected students ranging in age from four to twenty-nine. Chimborazo School became a part of the City of Richmond's newly established public school system in 1870.