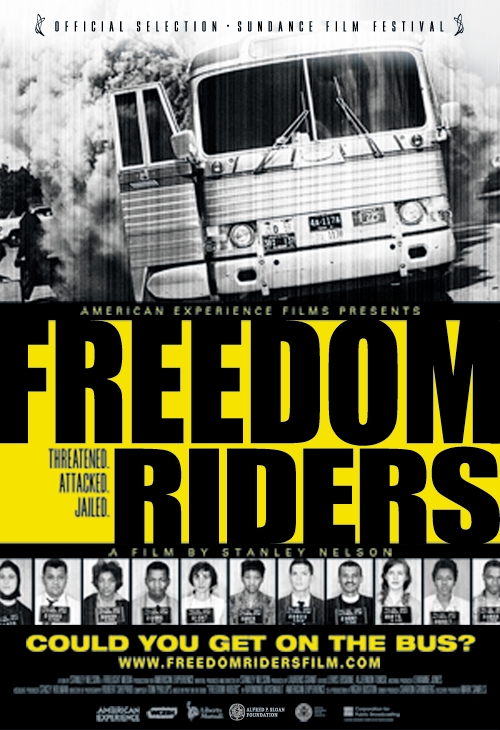

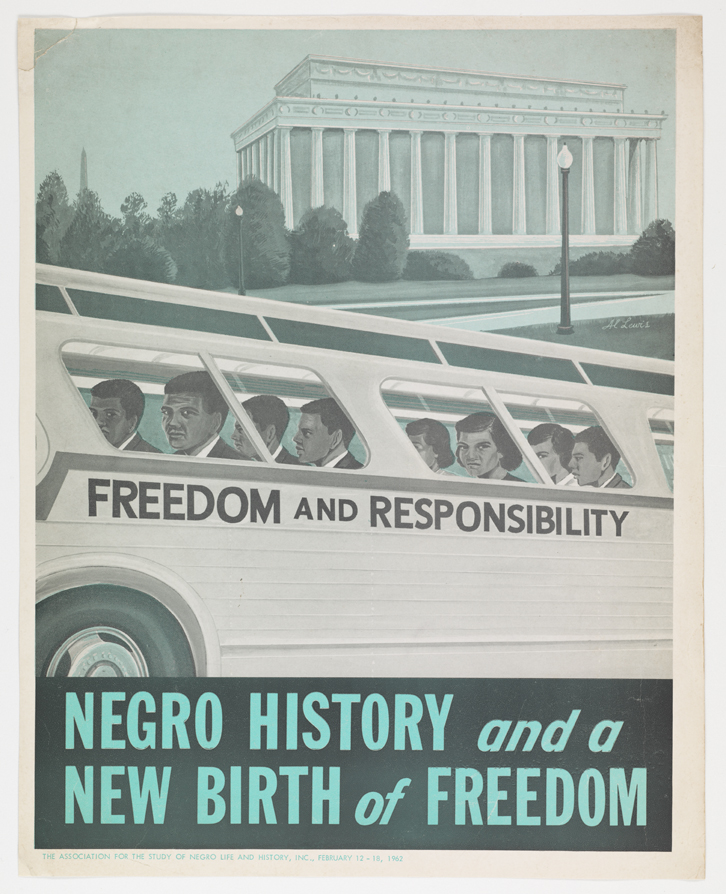

In 1961, a small group of white and black volunteers rode public buses into the South to demonstrate that interstate travel facilities remained segregated in defiance of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Freedom Riders faced arrest and beatings in their efforts to compel the federal government to enforce the law.

When we think of the modern civil rights movement, we often think about events in the Deep South. Images from Virginia rarely appeared on the nightly news as the commonwealth avoided much of the state-sanctioned violence that occurred in Alabama and Mississippi. Nonetheless, it was often legal decisions in Virginia that provided the justification for federal involvement in the ending of Jim Crow.

Similarly, when we think of the Freedom Riders, we recall the iconic image of the burning Greyhound bus outside Anniston, Alabama, the Klan-led beatings at bus stations in Birmingham and Montgomery, and the arrest and subsequent imprisonment of the protesters at Mississippi’s infamous Parchmen Farm. We don’t think about Virginia. But court cases initiated in the commonwealth played an important part of the Freedom Rides by providing legal groundwork that led to the ending of segregation in interstate transportation.