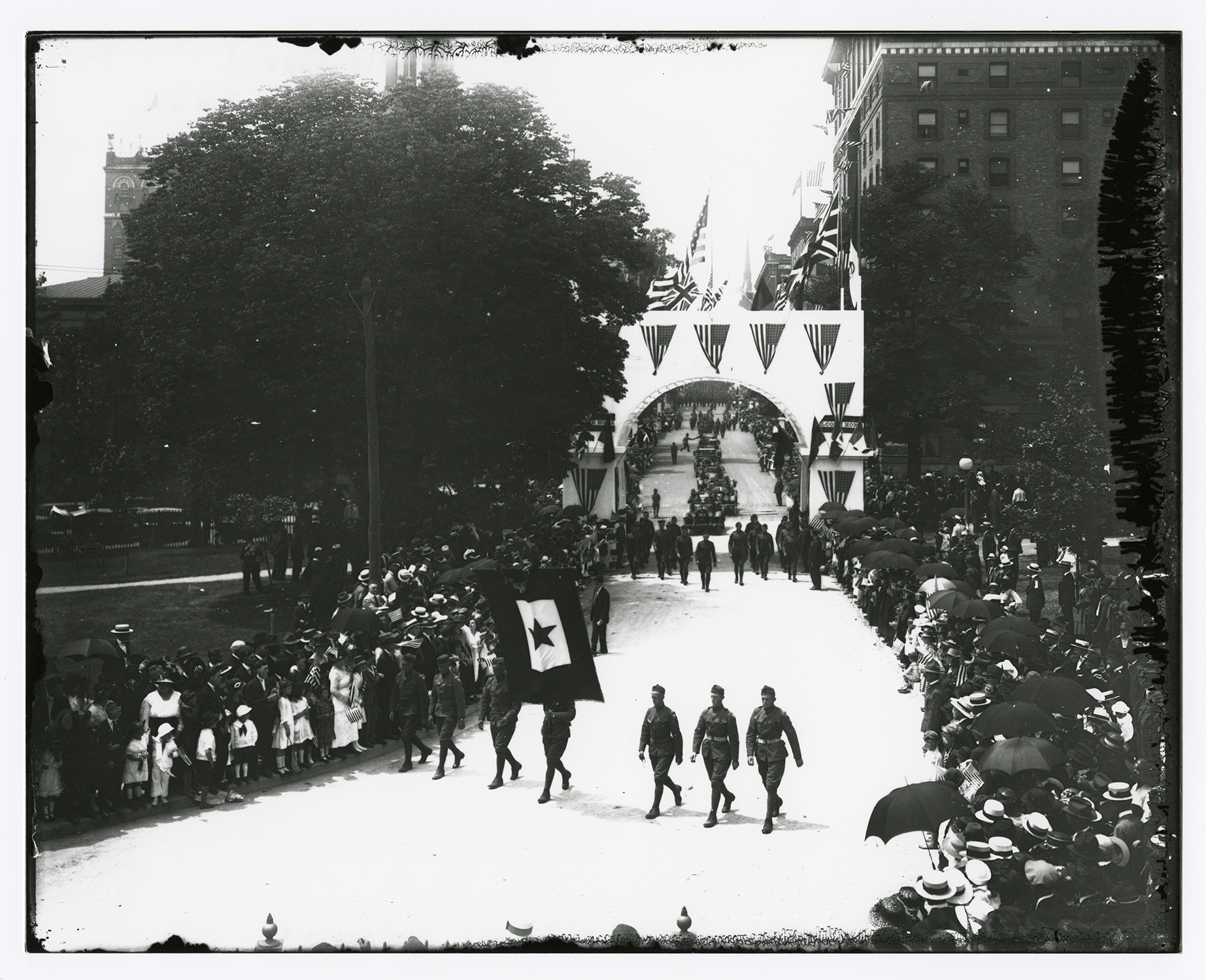

Returning Home

The guns of the Western Front fell silent on November 11, 1918. The armistice marked a victory for the Allies, including the United States, and defeat for Germany.

When asked after the war how his overseas experience affected him, Capt. Thomas Hardy of Farmville, Virginia, responded that he “learned to love America better and to hate war worse.”

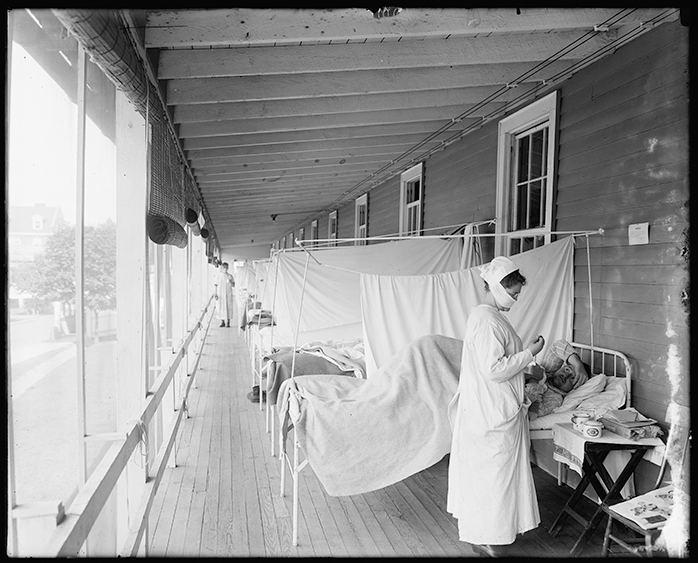

Those who returned home were fortunate to have lived through the horrors of war. Some veterans carried home physical evidence of their service. Many others suffered unseen psychological injuries for which there was much less understanding or treatment than today. They were welcomed by families also changed by their own wartime sacrifices. African American veterans who fought to “make the world safe for democracy” would continue the struggle for equal rights at home.

This article was featured in the Virginia Magazine of History & Biography, Vol. 126, No. 1 in connection with the The Commonwealth and the Great War exhibition.