European, as well as American artists—even if they never visited Natural Bridge—were eager to depict it on account of its fame. They presented it simply as a remarkable American landmark. By mid-century it was so well known that it appeared as a metaphor in one of the greatest of American novels, Moby Dick. Describing the great white whale, Herman Melville wrote in 1851:

"But soon the fore part of him slowly rose from the water; for an instant his whole marbleized body formed a high arch, like Virginia’s Natural Bridge, and warningly waving his bannered flukes in the air, the grand god revealed himself, sounded, and went out of sight."

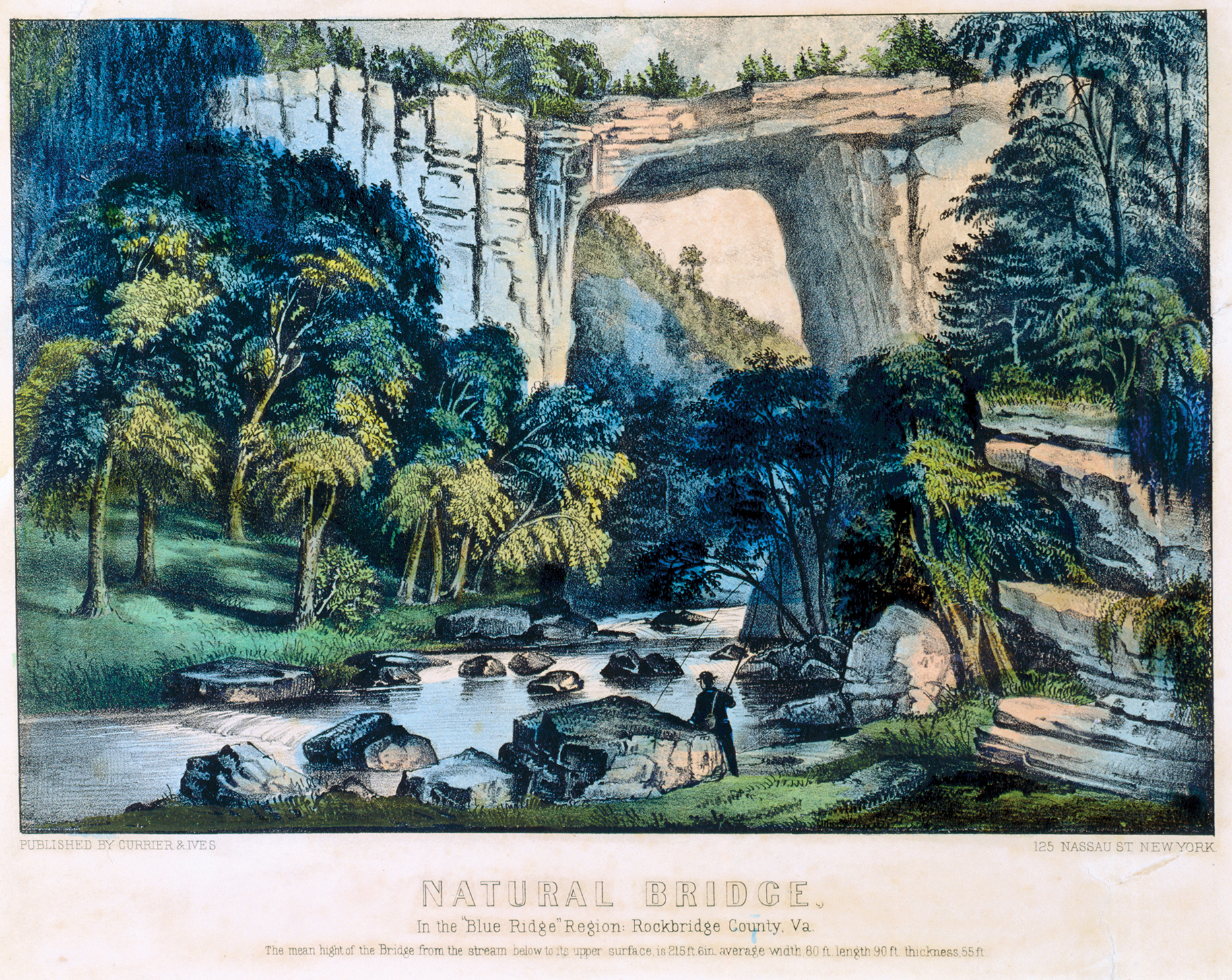

A decade later, the bridge was sufficiently appreciated to be the subject of a popular Currier and Ives hand-colored lithograph.

For at least a few years after the Civil War, visitation to Natural Bridge by non-Virginians plummeted. “There was a time when the Natural Bridge was esteemed among the greatest wonders of the continent,” lamented the editor of The Virginia Tourist in 1870. “Of late it has languished in obscurity and neglect,” he continued, “visited only by stray travelers from the Virginia springs.” However, the recognition of Natural Bridge in that same decade in both Picturesque America and The Great South would produce a brief upsurge of tourism as well as a new burst of artistic creativity.

When the Virginia artist Flavius Fisher painted Natural Bridge in 1882, it had become more accessible than ever to tourists, due to the building of railroads into the Shenandoah Valley. The artist pictures more than a dozen visitors at the base of the arch. To them the bridge was a spectacular but not mysterious site, for it had become accepted that this wonder was created by slow erosion rather than some unfathomable cataclysmic event.

By 1882, the second summer of heightened awareness of Natural Bridge was nearing its end. The establishment of Yellowstone National Park, and the production of huge panoramic paintings of the Grand Canyon had given a new dimension to the term “wonder of nature”, and by this standard Natural Bridge did not seem to measure up. After 1900 it descended permanently into a secondary role among the works of nature. Nonetheless, precisely because it had “sounded” so loudly in the nineteenth century, Natural Bridge never did fall “out of sight.” The stereo card and postcard industries had only begun, and they would carry the fame of the bridge throughout the twentieth century. In 2016, the inclusion of Natural Bridge within the Virginia network of state parks, due to its historical importance, elevated its status and assured its preservation and a continuation of its fame.