It is, from the outside, unremarkable. With a coat of faded red paint and a crude hand-forged hasp to secure its lid, the simple pine chest – once used to store tools, seed, or feed – could have easily been discarded.

But when it was recovered from a Mecklenburg County barn in 2010, its contents yielded unexpected treasures. Hundreds of letters, dozens of cards and postcards, contracts, farm journals, receipts, and newspapers were packed inside.

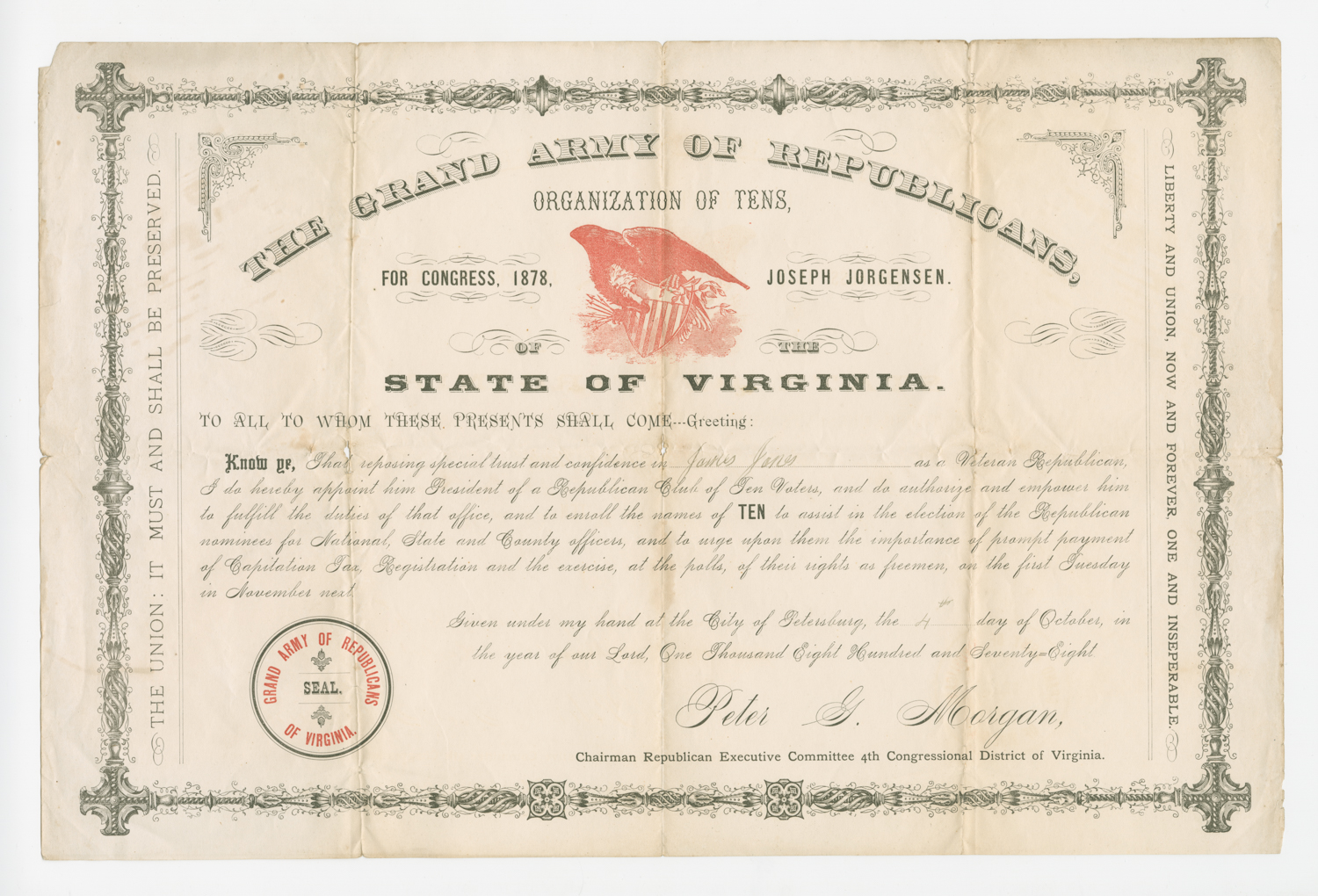

And one of them – an 1878 certificate issued by The Grand Army of Republicans to Prince Edward County sharecropper James Jones – illustrates the determination of Black Virginians to achieve the promises of emancipation.

Born into slavery, Jones was 14 when the Civil War ended in 1865, and he came of age as millions of freedmen across the South sought the rights of full citizenship. Jones married Charity Scott in 1872, and the following year, he likely exercised his right to vote for the first time.