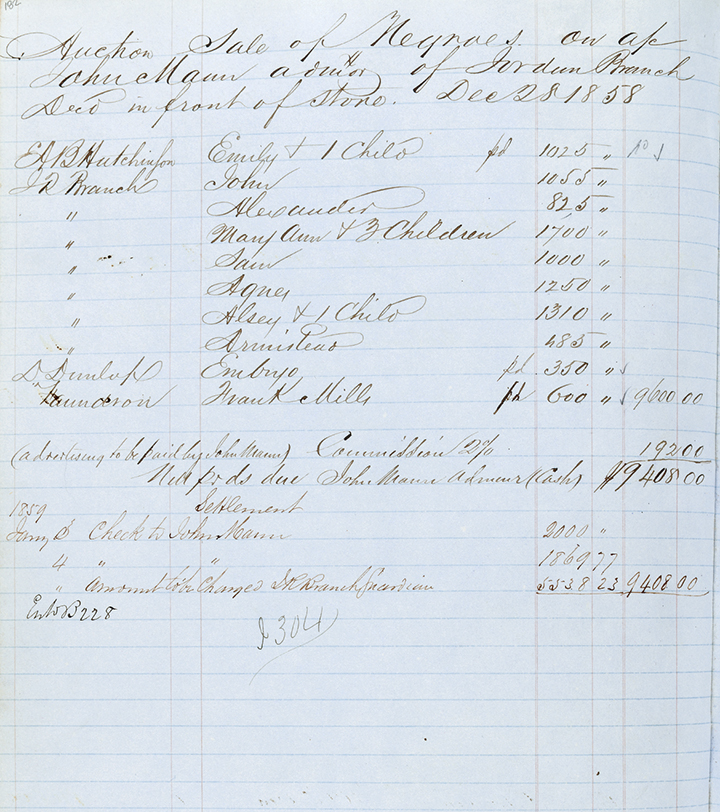

The names of some Virginians roll off the tongue of Americans like water. More than 900 books have been written about our first president, who has a profound legacy in our state and our nation. But the stories of lesser-known Virginians are important as well. There are many who never knew fame or acquired fortunes yet persevered against overwhelming odds. They also left legacies in the form of their descendants who have benefited from and built upon their tenacity. Emily Winfree is one such individual. Winfree, an African American woman who lived through slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, never gave up, always kept her family together, and ultimately prevailed.

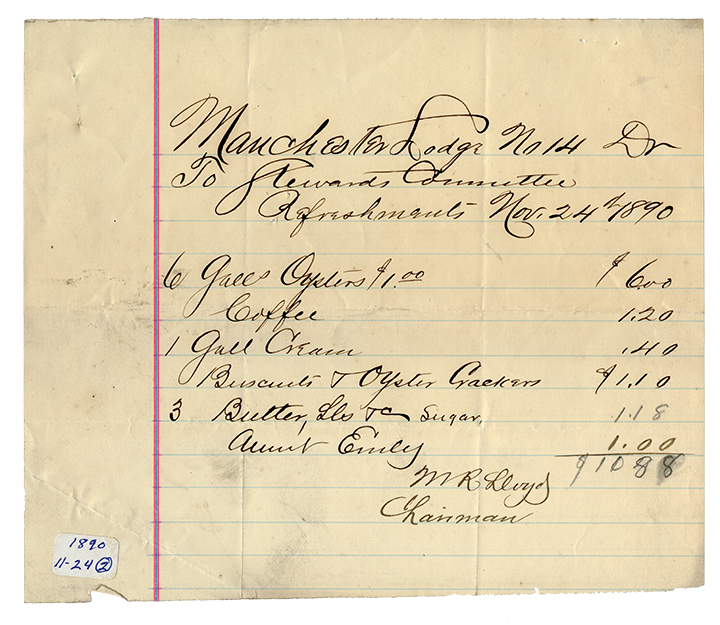

The name of Emily Winfree became known to Richmonders in 2002, when a small cottage in Manchester was about to be torn down to enlarge a parking lot. This structure was the sole survivor of hundreds of similar homes built during Reconstruction. The Association for the Conservation of Richmond Neighborhoods (which no longer exists) realized the cottage’s historical importance and managed to rescue it at the last minute. Having found no permanent home, today “Winfree’s Cottage” sits on a trailer below Interstate-95 adjacent to the site of Lumpkin’s Jail in Richmond’s Shockoe Bottom neighborhood. The cottage was said to be the home of Emily Winfree, given to her after the Civil War by farmer and physician David Winfree who was Emily’s former owner and father of several of her children.