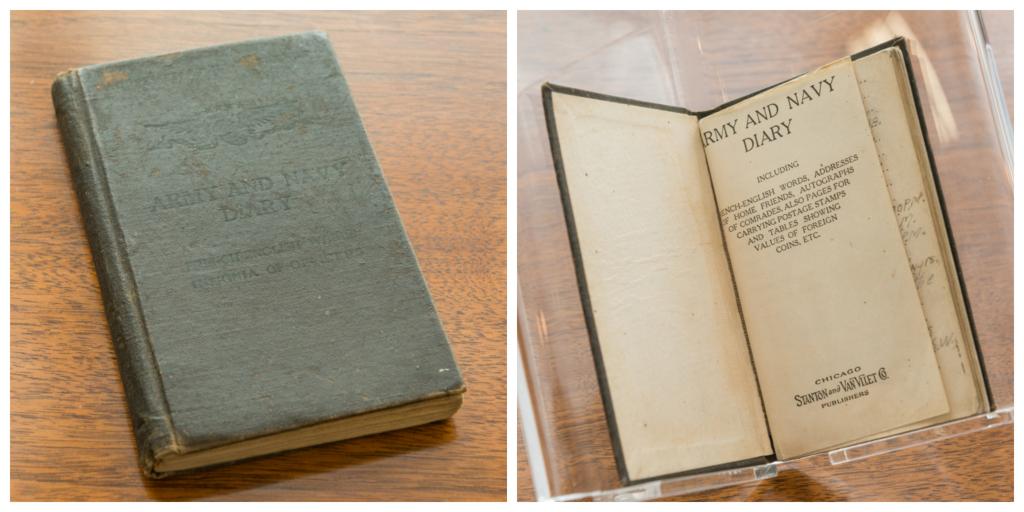

In 1918, 27-year-old Hugh E. Mosher left his home of Roanoke, Virginia for the battlefields in Europe. During his time in Co. B, First Battalion, 602nd Engineers Regiment of the American Expeditionary Force, Hugh continually updated a diary describing his experiences in the war while sending letters and postcards to his friends and family back home. These documents, alongside an extensive memoir written after the fact, were gifted to the Virginia Museum of History and Culture by Hugh's sister, Anne M. Copley, in 1981, one year after his death.

Mosher's Memoir: WWI from a Virginia Soldier's Point of View

Hugh's writings provide insights into life as a Virginia soldier abroad during WWI and paint a detailed picture of the last few months of World War I and the months following. Through them, readers can better understand the struggles that a soldier may have faced back then, but also how exciting it could be for him to enter a foreign land.

In commemoration of the World War I Centennial Commemoration, excerpts from this article thread were posted to our Facebook page "in real time" on or around the same days Hugh wrote his entries, 100 years later.

To view these items in person, please visit our library and request the VMHC Manuscript Collection # Mss1 M8533 a.

Brest, France (July 22, 1918)

Hugh and the rest of his unit arrived in Brest, France on the coast of Brittany after three months of training and twelve days at sea. The weather was rainy and the citizens did not cheer “as these people were worn out with the war and alien soldiers and other hardships.” Hugh also lost all of his personal belongings to thieving soldiers upon arrival. Despite these setbacks, he remained optimistic. He made note of the rich history and culture of the country by remarking on the cobbled streets, learning his first French words, and bathing in an old fortress of Napoleon’s. “I think I’m going to like it,” he wrote.

Part 1 of Torcenay (July 27-September 15, 1918)

Shown here is a photograph from Hugh's collection of two of his commanding officers, Capt. Krumm, along with Lt. McGallow [identified as McAllen by a descendant]. You can see Hugh's handwriting on the back, identifying them.

After a few days on the coast of France, Hugh headed east through the cities of Tours and Orléans. On July 27th, he settled into camp in Torcenay, a small village with only three stores in its business section. The town’s largest building was a Catholic cathedral, which Hugh visited every Sunday while camped there despite not understanding the language. Of the 1,000 men in his regiment, over 800 were Catholics. Hugh believed he was the only Episcopalian in his Company. Right outside the village were farms that celebrated a communal lifestyle, giving milk, cheese, butter, and eggs to the soldiers. Some of the Americans, not accustomed to wine, became drunk in the first days at Torcenay and were scolded by their commanding officers.

Being hundreds of miles south of the Belgian border, Torcenay was removed from the fighting between the Germans, French, and Americans. Hugh's Co. B spent this time training by drilling with bayonets, cleaning rifles, hiking with gas masks, and standing on guard duty. Here, he watched French and American troops pass through the town by train as they headed to the battlefield. A German plane passed over the town daily, observing them. On Aug. 4th, Hugh and his men inspected an old fort last used against the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. The guns were moved to the front. Hugh wrote in his memoir, “We are still in ignorance as to what will be done with us. We know we are somewhere near the action.”

Part 2 of Torcenay (July 27-September 15, 1918)

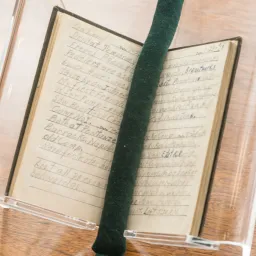

Shown here is the letter from Adele to Hugh on April 3rd, 1920.

Hugh continues his stay in Torcenay and befriends the locals, particularly the Guyer family. He has dinner with them often and learns French from their daughter, Adele, while he teaches her English.

He reflects in his memoir, “I visited one family several times whose daughter -Adele Guyer- was about sixteen or seventeen. I wonder where they all are now. I was invited to have meals with the family several times. The family sat at a long table in the dining room with the father and mother at the ends. After a devout and lengthy blessing we were served meat by the mother and bread by the father. - also jams, cheese, wheys, strong coffee.” He talks a lot about the food and how it was prepared, observing that, “good hard, fresh baked French bread can’t be beat.” After the meals, he describes how, “Father reads the paper and Adele plays the violin for us. She has some natural talent but it is obvious that she has had no training.”

On August 18th, Adele’s brother returns home from the war after being injured. Hugh remembers, “Mamselle Guyer’s fourth brother was brought home. He was shot in the thigh but he will live. I tried to comfort her with my vocabulary of ten French words.”

Hugh and the Guyers continue to exchange letters after he leaves Torcenay. In April 1920, Adele responds to a letter from Hugh when she returns home briefly from school in Wassy (about 65 miles from Torcenay) where she is studying commerce. Writing in English, she says, "But you will have correct me many mistakes, my sentences are so bad," and asks Hugh if he still knows French, instructing, "Write me in French, if you can and I'll correct your mistakes." She describes how she continues to play the violin and practice English, how her brother is a sous-chef for the French railway, and writes, “My mother and father speak with me very often about you and we are very happy to know that you will come very soon in France and at first, at Torcenay? We are hoping that your Government will allowed your request!” It is unknown if Hugh ever returns to France.

Part 3 of Torcenay (July 27-September 15, 1918)

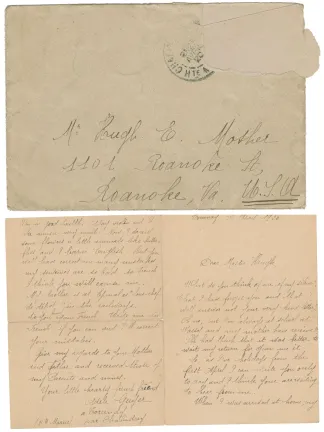

Shown here are the French-English dictionary Hugh bought in Langres, France, and a postcard of French washerwomen, like the one who attended to Hugh’s clothing. On the back of the postcard, Hugh wrote "Typical French Community Washing Basin, Torcenay (Hautemorne)".

Hugh spends his final weeks in Torcenay with a mix of training and leisure.

He writes about the exercises and drills he and his unit perform, including training with gas masks, bayonet dummies, and a change from battalion and parade drills to practical fighting movements. He reflects, “As these drills become more realistic we felt tension building up at the approach of actual combat. We never know when the next order would be to the front.”

In between training, Hugh and his unit attend to chores and have some time for leisure. He sees a baseball game, goes to a movie in Chaumont, and continues practicing his French. They visit Langres, of which he writes, “This is our first big city. It was full of antique buildings, winding streets, a fort, and a cathedral. I had a steak dinner at an American YMCA, saw a French funeral from the cathedral. I bought an English-French dictionary.” Hugh’s fascination with big cities and old buildings is a recurring theme during his stay in Europe. He also runs into two men who, like him, are from Roanoke, Virginia – Lt. Ernest Baldwin and Billy Beal – at a rest billet near Torcenay. Billy is the son of Hugh’s mother’s cousin.

Hugh is able to have his clothes laundered, writing, “Found an old French woman who did up all my clothes which hadn’t been done for 18 days and needed it badly. They were done beautifully.”

And on September 9, 1918, Hugh celebrates his birthday, recounting, “September 9— My birthday- 28 years old- A downpour of rain. Had supper at Chaumont Chemin de fer- the [b]est I have had in a long time. There was some music going on.”

Hugh and his unit leave Torcenay on September 15, heading for Ancemont.

Ancemont and Aubreville (September 23, 1918)

Shown here is a postcard of the artillery company outside of Aubreville. Hugh's handwritten note on the reverse reads "Pacing 8" pieces Artillery Aubreville".

Hugh and his unit arrive in Ancemont at 8:00 am on September 16 and discover a much different atmosphere from Torcenay. Writes Hugh, “We witnessed an air battle and anti-aircraft guns at work. We passed a cemetery, and could see how the tops of buildings had been shot off. This is in rolling country. The enemy were trying to hit and destroy a hospital.”

Only two days later, Ancemont is bombarded at 4:00 am and Hugh’s unit heads north on a 15-mile hike to their fourth camp near a village of which Hugh never learns the name. They arrive on September 19 and discover the village has been “shot to pieces.” On September 20, Hugh writes, “German planes were hunting for our location. We were moving forward with creeping maneuvers. When nothing is in sight we walk or run- when the enemy is in sight we find cover.”

The next day they hike at night to their fifth camp, Aubreville, to complete road work near an artillery company that has several men from Roanoke, Virginia, including Roy Smith and Clyde Cocke. Hugh will see these two again in Cheppy in mid-October. On September 22, Hugh records how “Two A. Co. men of the 602 Engineers were killed by shrapnel falling on their tent.”

---

Shown here is a postcard of Road construction by Hugh and his unit near the Argonne woods. Hugh's handwritten note on the reverse reads, "Rapid constr. corduroy road, Argonne Woods".

On September 23, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive begins. Hugh and his unit work on repairing roads, during which they observe several air battles and “all caliber of artillery making greatest concentration of fire used on the enemy in this war. […] Pershing got his first chance to show what Americans could do. Pitted against us was the strongly entrenched 4 year old Hindenberg Line.”

At this point, German trenches are only one mile away from Hugh and his unit. Americans fire at the German troops with mortars for six hours and German forces begin to retreat. Hugh’s outfit is ordered forward; he reflects how, “It all blurred in my mind but I know we saw many German dead as well many French and American wounded. What a sight that was. We helped the Red Cross remove the wounded as this terrain had to be cleared for the advance of artillery and its emplacement. In many cases because of lack of time the dead had to be buried in the abandoned trenches. There was no sleeping that night.”

Hugh writes to his father, Hugh O., about the battle: “Night 25th Sept…. At 11 PM when the big show started ‘twas Dante’s Inferno personified. Gee, how the old earth rocked. The Lord took care of his own for that night and some several to follow.”

Avocourt (September 26)

Shown here are Hugh’s postcards of the destroyed village of Avocourt, on the reverse of which he has noted "Avocourt 9-26-1918 which 602 passed on pushing Art. advance".

The push on the Hindenberg Line has continued for almost a week, as Hugh and his unit continue to repair and rebuild roads to allow for access by troops and equipment. Consistent rains make this work even more difficult.

On September 26, German troops have been pushed back almost eight miles, with some being taken prisoner amidst the retreat. Villagers are wounded, the sick drop out of the ranks, and the Americans have left their food behind to pursue the fleeing Germans. Hugh has had no food for the past five mealtimes except for emergency rations. “Today I feel that I really am in a war,” he writes.

The next day, Hugh and his unit arrive at their sixth camp, Avocourt, in pursuit of the fleeing Germans. The following day, they are bombed by gas shells and machine gun fire takes down many Americans. “The sight of hundreds of dead and wounded horses was horrible,” Hugh writes of the battlefield. “They had to be shot if wounded and dragged to trees where they [were] hoisted to limbs and left hanging there to get them out of the way.”

By September 29, the Germans are 10 miles away and American troops are still without provisions. Hugh continues repairing roads throughout early October as the Americans chase after the Germans.

Cheppy (October 6, 1918)

Shown here is a page from Hugh’s letter to Nora, written on YMCA stationary, and one of his postcards from Cheppy. Hugh's handwritten note on the reverse of the postcard labels it as "Cheppy - 'Argonne Hell'".

Heading out from Avocourt, Hugh and his unit hike the four miles to the village of Cheppy, where they will remain for more than two weeks. During this time, Hugh reflects on the recent loss and tragedy he has witnessed as well as his life back home. On October 6, he writes, “My good friend, Von Every of Chicago, died in the hospital today of wounds. Witnessed the burial of 500 Americans and French together. They were all placed in a common grave, then they were covered up. Taps was blown. It was very impressive.”

While in Cheppy, Hugh meets friends from Roanoke and finally has time to write to his family. “I met Lt. Roy B. Smith of the 56th Infantry, an old friend from Roanoke, Virginia while we were still working on roads," he writes on October 12. "We chatted about home and old friends before we pulled out.” Two days later, he reports, “Met Clyde Cocke, Gally Hammond, and Sidney Chockley of the Hdq.Co. 42nd Division from Roanoke. This was the well known Rainbow Division, made up of men from 30 states.”

Writing to his adopted sister, Nora B. Sandford, a Red Cross nurse in France, Hugh observes, “So many months have passed since I last wrote I don’t know where to begin. Evidently when you last heard I was somewhere in France. I am still but somewhere else. It has seemed quite different from the first Chapter of France. From tranquility to a Boiler Shop.” Nora forwards this letter to Hugh’s mother, Louisa Mosher, back in Roanoke, writing on October 16, “I’ve just received a sweet letter – sweet because it’s from Hughie and I’m sending it on to you as he asked me to. I understand so well how hard it is for him to get a letter written and appreciate a message from him all the more.”

Louisa then writes to Hugh’s older brother, Sgt. William Mosher, who is also stationed in France in a veterinary hospital. William is relieved to hear his brother is alright, writing in reply to his mother, “You don’t know how glad I was to hear that you had heard from Hugh. I sent his letter right on to him that evening. I was going to write his commanding officer about him that night to find out about him.”

Cierges (November 2, 1918)

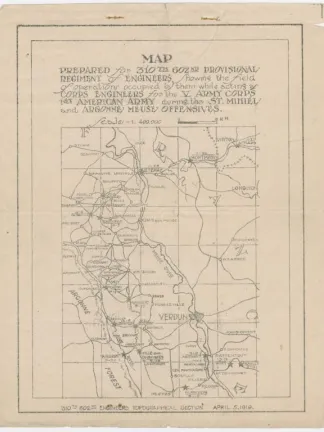

Shown here is a map of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive used by Hugh's unit.

Hugh’s company leaves Cheppy for Cierges, their 8th camp, on October 24. “This was the first village in France we found intact,” reflects Hugh. “We arrived at night and there were scenes of the recent drive everywhere- abandoned German equipment and horses killed. It was an oddity to see such destruction and yet the village had not been damaged. No doubt the Germans were in such haste to retreat that they had no time to demolish the town.”

Hugh is oddly comfortable hanging out in a dugout that some of his unit find with some French soldiers while a battle occurs on and off right around them. “We decided to sleep there and it was a joy after months of sleeping on the ground,” he writes. “I have a fine moustache and goatee growing.”

Hugh spends time with the French unit, from whom he purchases a “1 pound shell polished and embossed with Fleur de Lisle design. The Frenchmen do this work right in the dugout in their free time. They made an allumette du fer (cigarette lighter) out of the copper firing device of a shell. We had hot coffee as shrapnel fire nearly took our kitchen away.” They ultimately lose the kitchen on October 30, of which Hugh writes, “Our dinner was disturbed by having our kitchen blown up. We thank kind Providence for its care this day.”

The German initiatives continue to fade off, with intermittent fire exchanged. Writes Hugh on October 27, “Think war must be coming to an end.” The final attack from the Germans in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive begins on October 31. “Johnson was killed and Sgt. Reiner was wounded by the shrapnel,” reports Hugh. “Thirteen comrades sleep with us in the dugout. Beginning offensive at midnight. It was an enormous scale.”

“All day under shell fire. Nothing to eat. Cold and foggy,” Hugh writes on November 1. “My shoulders are sore from carrting wounded to the ambulances and unloading at the hospital. The wounded are American, French, and Germans.” The following day, things return to normal. He spends time in the dugout with the French soldiers again, calling them “bon comrades.” They give his company wine, cognac, and bread. “We enjoy their good French bread,” he observes, “but they do not think much of ours.”

Barricourt (November 11, 1918)

Shown here is a postcard of a bridge built by Hugh's Co. B from Barricourt to Stenay with the caption, "Bridge open to traffic / road to Stenay / 11/16/18." Hugh's handwritten note on the reverse reads "Last Canal Br. into Stenay".

On November 4, Hugh and his unit leave Cierges for Barricourt, several dozen miles to the northeast and near the Belgian border. Three days later, he writes, “We got news that two German Generals came through our lines carrying white flags to talk peace terms with General Foche. It looks like the beginning of the end. It takes time to make a peace.” On November 9, he sees his old French friends again. They give him an “allumette de fer” or cigarette lighter that they made for him.

“GREAT NEWS- At 11AM this day the Armistice was signed," writes Hugh in his memoir of November 11, 1918. "Goodbye helmets and gas masks. On that day shell fire stopped and out ears rang with the silence. Gradually from horizon to horizon the guns were silenced and yells of joy came out of the trenches- friends and foe. Germans, French, and Americans came out into the open to see if it was really true.”

In a letter to his father, he writes, “Then on the memorable day 11/11/18 at 11 AM comes new of signing armistice. Such unbounding joy by everybody of all races.”

Shown here is a bridge built by Hugh's Co. B from Barricourt to Stenay. The caption reads "Bridge open to traffic / road to Stenay / 11/16/18."