Long before English colonists arrived in Virginia, American Indians relied on oysters and other fish and shellfish for sustenance. Archaeological evidence indicates that for thousands of years indigenous people usually harvested oysters in the same location. Over time, the oysters’ size diminished due to a shortened lift cycle before being harvested, which in turn forced native fisherman to search for new sites to fish. When English colonists arrived, they were ill-equipped to fish for themselves and hired Virginia Indians to fish and harvest shellfish for them — placing even further demands on the mid-Atlantic crop.

Oysters in Virginia

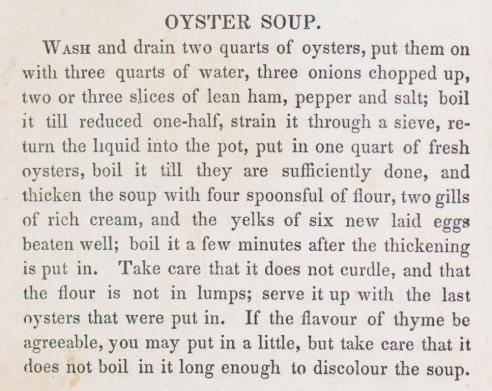

Oyster soup recipe from "The Virginia Housewife: or, Methodical Cook by Mrs. Mary Randolph" (VMHC Rare TX715.R214.1838)

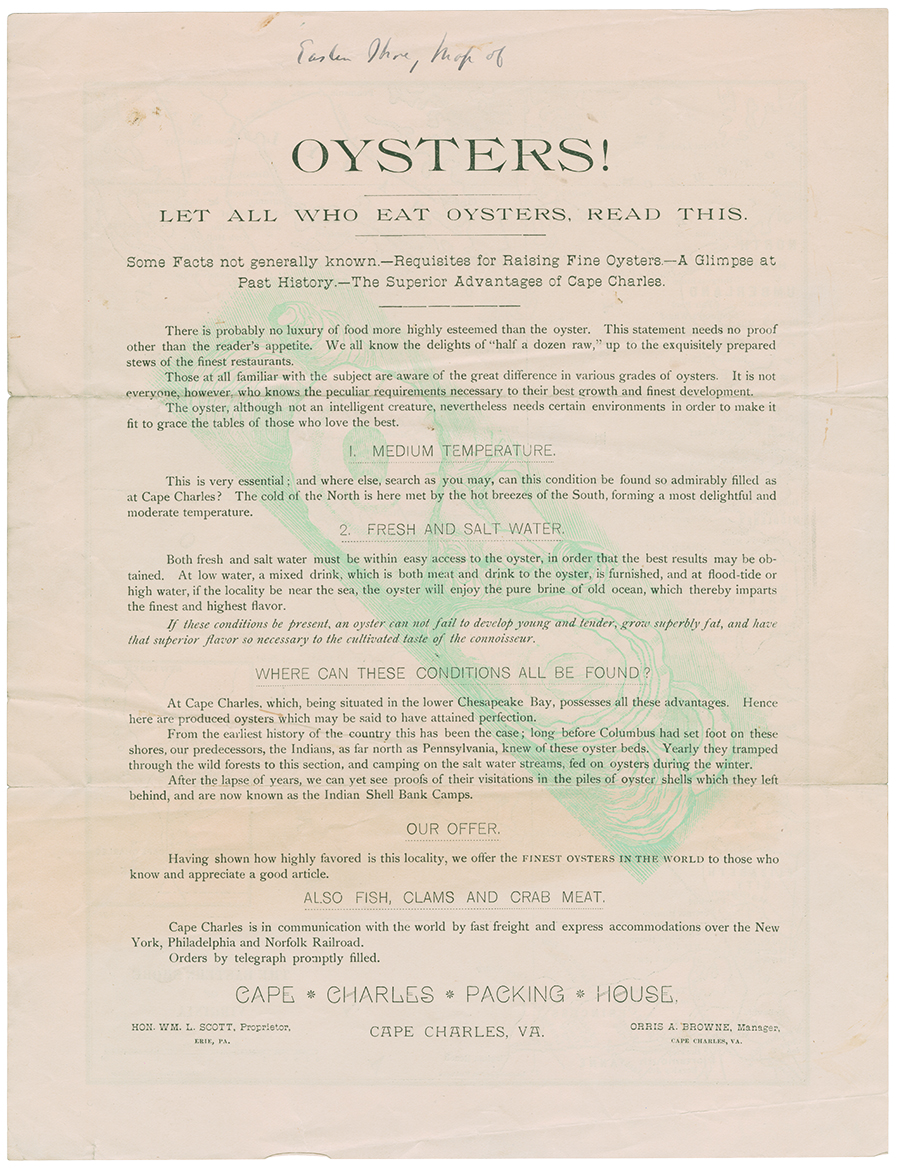

Because of their abundance and proximity, oysters quickly became a staple of the colonists’ diet. Prior to the 19th century, when food preservation techniques evolved, shellfish was harvested and consumed only within the Old Dominion. As canning became more prevalent in the 1800s, oysters could be packaged in coastal cities for transport on railways further inland, again expanding demand.

While considered a delicacy today, earlier in America’s history, oysters were cheaper than beef and were a staple on menus at homes and in restaurants. Cookbooks from the Virginia Museum of History & Culture collections feature a variety of typical recipes, such as oyster soup, as well as more exotic concoctions like pickled oysters, and oyster ice cream. Pubs and taverns frequently offered oysters to be enjoyed with beer and ales.

Image of an E. J. Steelman's Cherrystone Oysters can, 20th century (VMHC 2004.362.2)

Oysters Today

As a result of oysters’ popularity in Virginia, they came to be distributed across America and to Europe, which resulted in vastly expanded exportation. Eventually, pollution and overharvesting led to environmental degradation; disease driven by a non-native microorganism also plagued the ecosystem. By the 1970s, Chesapeake oyster production was at an all-time low, and within a decade the regional industry was nearly moribund. Since that time, however, extensive conservation work has resulted in replenished oyster beds. In 2016 some 40 million oysters were sold in the Commonwealth.

Virginia oysters have come a long way, and are more popular than ever — and have reclaimed their place in Virginia’s food culture, tourism, economy.

Did you know?

-

The Eastern oyster is sometimes called the Atlantic or American oyster, but its scientific name comes from Virginia — Crassostrea virginica.

-

Wild oyster populations in the Chesapeake Bay have declined to less than 1% of their historical numbers.

-

Each day, 1 oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water!

-

Virginia is the number one state on the East Coast for oyster aquaculture.

The Nature Conservancy Chesapeake Bay Oyster Recovery

The Nature Conservancy’s oyster-restoration efforts in the Chesapeake Bay have primarily focused on native oyster reef restoration, while simultaneously supporting wild oyster populations and a growing commercial oyster industry. The oyster industry in Virginia is the most productive on the East Coast, providing sustainable seafood and green jobs. The Nature Conservancy and their partners have restored more than 392 acres in Virginia. By 2025, their goal is to restore native oyster reefs to sustainable levels in 10 Bay tributaries.