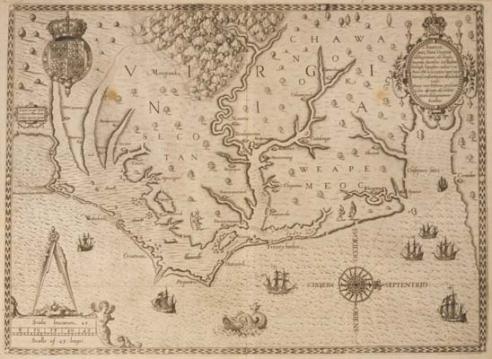

In 1590, John White's Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta was published. Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta depicts the Outer Banks coastal region around Roanoke Island north to tidewater Virginia. It is the first separate map of “Virginia” and the first printed record of Sir Walter Raleigh’s attempt to establish a colony in North America. On the map, the Chesapeake Bay is named for the first time as “Chesepiooc Sinus.”

Historical Context:

John White, an English artist, explorer, and cartographer, likely joined an expedition to America in 1576 in search of precious metals and the Northwest Passage to Asia. White’s skillful illustrations of the Inuits in Greenland was later brought to the attention of Sir Walter Raleigh, who was planning a series of voyages to America to establish a permanent colony that could enrich the English and enable them to Christianize the natives.

White wrote in 1593 that he had made five voyages to North America, so it is likely that he accompanied Raleigh’s first expedition, which was authorized by Queen Elizabeth I in 1584 to explore and colonize an area north of Spanish Florida. The explorers reached Roanoke Island in the Outer Banks of North Carolina and named the entire region along the Atlantic coast “Virginia.” Raleigh ordered them to survey the coast ahead of a larger expedition planned for the following year. They returned to England with two prominent Indians: Wanchese, an adviser to the Roanoke weroance, or chief, and Manteo, a son of a female chief of the Croatoan island tribe.

After studying the culture and language of the Algonquian-speaking natives, White and Thomas Hariot joined the second voyage to Roanoke in 1585. Led by Sir Richard Grenville and accompanied by 600 colonists, mostly military men, they were charged with drawing, mapping, and recording details of the natives and landscape. They joined a party to the mainland, where White encountered and illustrated the towns of Pomeiooc, Aquascogoc and Secotan. Grenville later returned to England and left about one hundred men under the command of Ralph Lane to build a fort and houses at Roanoke, which antagonized the local Indians. During the winter, White and Hariot sailed north to the Chesapeake Bay, where they visited the Chesapeake capital of Skicoak and other Algonquian towns.

By the summer of 1586, interaction with the natives had turned hostile, and the colonists left Roanoke with Sir Francis Drake, who had arrived unexpectedly. Grenville, who reappeared in 1586 too late to relieve the colony, left a small group of men to hold the fort, but they were killed by the natives. The following year, Raleigh attempted again to establish a settlement, this time to be built near the Chesapeake Bay, where the Indians seemed friendlier and the water was more navigable. His corporate charter named John White the governor of the new colony that would build the “Cittie of Raleigh in Virginea.”

White arrived in the summer of 1587 with more than one hundred colonists, mostly laborers, farmers, and their families, including his own pregnant daughter, Eleanor White Dare. He ordered the pilot of his flagship Lion to stop at Roanoke to check on the men left by Grenville, all of whom had disappeared. After determining to keep the settlers at Roanoke, White returned to England to resupply the colony, leaving behind his daughter, son-in-law, and newborn granddaughter, Virginia Dare. In 1588, Grenville prepared to relieve the Roanoke colony, but was diverted to battle the Spanish Armada. White had to wait for the war with Spain to end for more ships to become available. He finally returned to Roanoke in 1590 and found that the fort and houses were deserted and the colonists had vanished.

White described in a report of his final trip that a small party in search of the colonists had discovered the word “CROATOAN” carved into a post at the site where the settlers’ houses once stood. White and the settlers had agreed that if they had to relocate during his absence, they should leave a message indicating their new location. A cross carved above the message would have been seen as a sign of distress, but to White’s relief, there was no cross. Since Croatoan was the home of Manteo’s friendly tribe, White hoped that at least some of the colonists had moved there. However, the privateers that had delivered White to Roanoke did not want to linger there during hurricane season, and a fierce storm prevented the party from sailing to Croatoan. White departed with another ship to the Caribbean and never returned to Roanoke. He likely retired to one of Raleigh’s estates in Ireland where he died in 1593 after writing an account of his final voyage to Virginia.

Archival Context and the Source:

Although the fate of John White’s Roanoke colonists remains uncertain to this day, his contribution to English colonization in North America is unquestionable. The scholarly and artistic work of White and Hariot encouraged investors and explorers to continue their efforts to settle permanently in the New World. The watercolors that White produced during his year-long travel throughout the mid-Atlantic coast are the earliest illustrated European depictions of Native Americans. A group of White’s original paintings are housed at the British Museum in London, but detail of their original creation remains somewhat uncertain.

White may have sketched illustrations from observation and used those sketches to paint finished products, from which he made subsequent copies. The British Museum owns the only extant paintings, which are either from his original master set or ones that he copied. Some of White’s originals were lost before reaching Europe when Sir Francis Drake’s sailors threw overboard a chest containing some of his work. The other source of contemporary renderings of White’s work outside the British museum are the Theodor de Bry engravings incorporated into the 1590 edition of A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia.

In addition to illustrating scenes of Indian life, White worked with Hariot to produce highly accurate maps which became models for cartography in America. Although some of these maps remained unpublished, others were printed, including a small map of Roanoke Island, and a large map of the surrounding region, featured in A briefe and true report.

Several engravings of White’s maps are in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society. These include Virginiae item et Floridae Americae provinciarum, nova description, the first map to identify “Virginia” north of Florida; Anglorum in Virginiam adventus, a map that depicts Roanoke Island surrounded by barrier isles; and Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta, printed in de Bry’s edition of Hariot’s report.

Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta depicts the Outer Banks coastal region around Roanoke Island north to tidewater Virginia. White created the original manuscript in 1585 during his and Hariot’s voyage. The 1585 map is now at the British Museum. White revised the map by adding names and more details of the coast using information he gained in 1587, and de Bry engraved and published the revised map in 1590. The copy of the 1590 map at the Virginia Historical Society is from de Bry’s Latin edition of Hariot’s work. Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta covers the stretch of coast from Cape Fear to the Chesapeake Bay. It is the first separate map of “Virginia” and the first printed record of Sir Walter Raleigh’s attempt to establish a colony in North America. On the map, the Chesapeake Bay is named for the first time as “Chesepiooc Sinus.”

John White’s original maps followed a north/south axis, but de Bry reoriented his engraved version of this map so that the north is shown to the right and the west is at the top. It was common for early maps to be oriented in the direction of the view of an approaching ship from western Europe.

This map was formerly part of the Coolie Verner collection acquired by Paul Mellon, who bequeathed it to the Virginia Historical Society in 1999.