In the earliest days of the Civil War, few expected the conflict to endure for four long years. As the Confederate capital, Richmond experienced waves of change that saw the city lurch from the untidy influx of thousands of military personnel and government officials in 1861 to the fiery evacuation of the city by Confederate forces in 1865. In that time, Richmond residents struggled with many challenges: the frequent threat of invasion; the onslaught of thousands of dead and wounded Southerners from nearby battlefields; the presence of hordes of rowdy soldiers, sutlers, and prostitutes, and hundreds of Union prisoners; and the departure of self-emancipated African Americans. Ernest B. Furgurson, in his book Ashes of Glory: Richmond at War (New York, 1996), maintains that "Richmond was by far the most expensive, corrupt, overcrowded, and crime-ridden city in the Confederacy" (page 191).

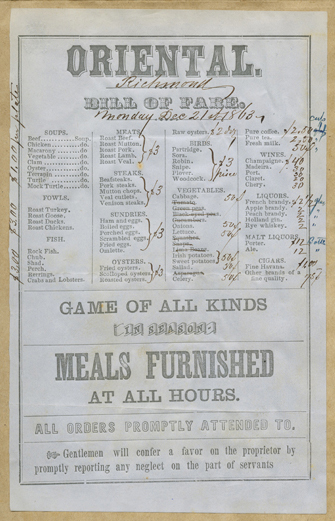

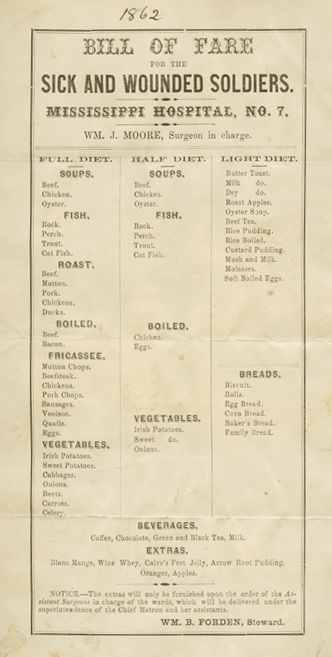

In this chaotic environment, adequate food supply for the dramatically enlarged population came to be a major challenge. Early in the war, Richmond's well-established and fluid markets kept pace with the growing demand. Howard's Grove hospital, on Mechanicsville Turnpike just outside of Richmond, employed a "traveling agent" responsible for procuring food and supplies on a daily basis. An 1862 menu from "Mississippi Hospital No. 7," a component of the large complex at Howard's Grove, offers a variety of vegetables and "fricassee"—including mutton chops, quail, and venison. Doctors could restrict their patients to a "Full," "Half," or "Light Diet."

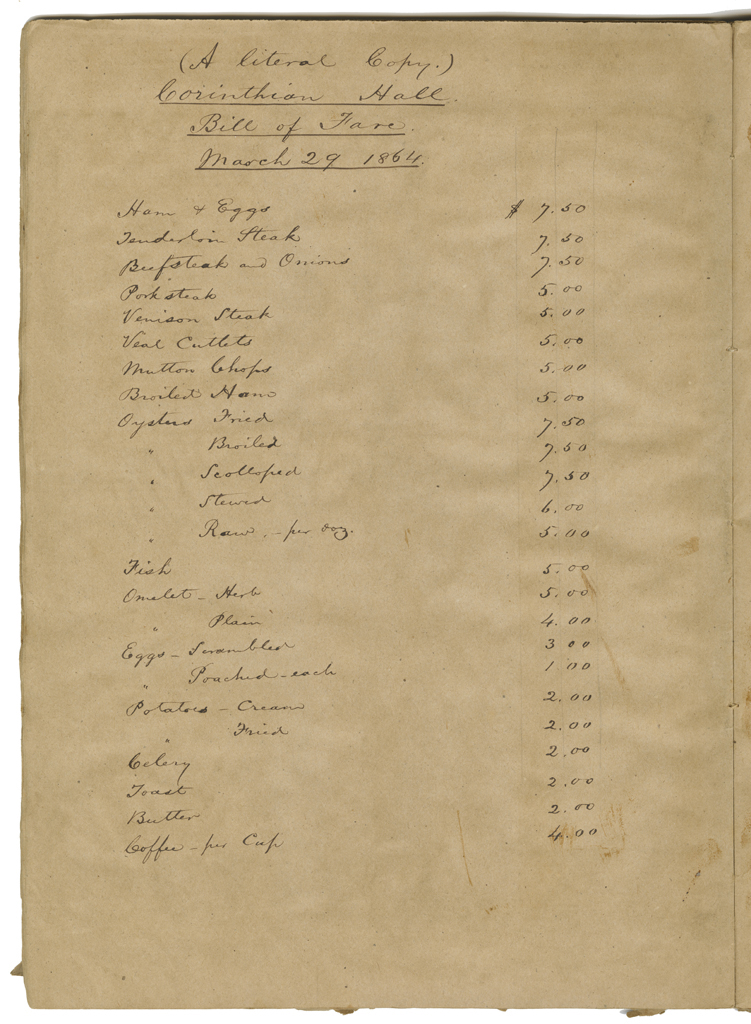

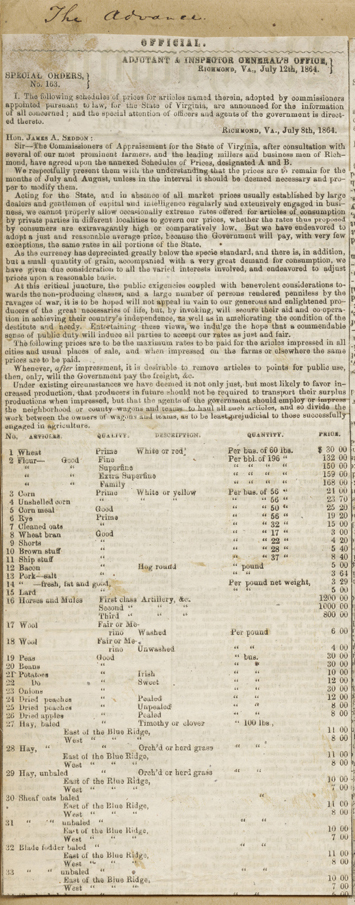

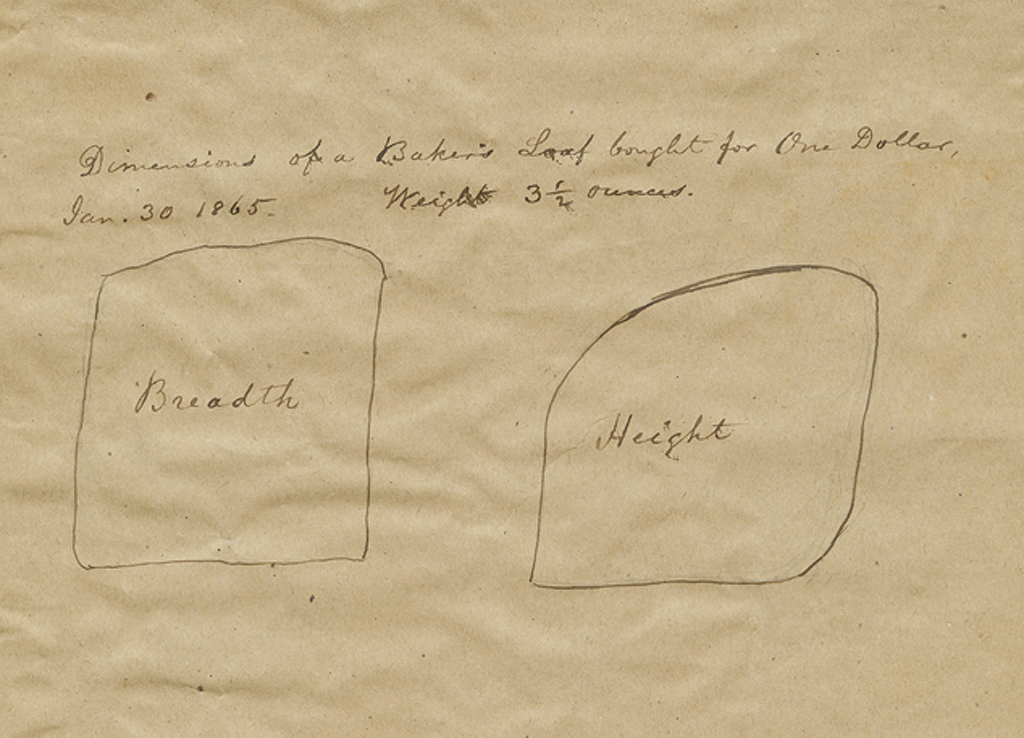

As the war dragged on, however, supplies dwindled sharply and prices rose dramatically. While the Confederate government struggled to maintain a stable currency, inflation steadily took its toll and forced officials to set limits on the prices that merchants were allowed to charge their customers. Retailers frequently ignored the government edicts, however, and failed to calm the financial chaos. The official limit for "superfine" flour, for example, increased from $25 per barrel in January 1864 to $150 six months later. Levin Smith Joynes (1819–1881), a physician in Richmond, kept a scrapbook in Richmond that detailed the precarious economy. By January 1865, Dr. Joynes noted that he paid one dollar for a three-and-a-half-ounce "loaf" of bread.

At the war's end, Richmond's population experienced another transformation when departing southern troops and Confederate officials were replaced by arriving Union army personnel, northern missionaries, and recently freed African Americans. In the immediate postwar period, many residents still suffered from food shortages. Over the period of one week in April 1865, Federal officials distributed some 86,000 rations to needy Richmonders. Gradually, normal agricultural and market activities resumed, but the dire situation in Richmond brought on by the Civil War would haunt those who lived through it.