After their army surrendered at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, the defeated Confederates returned to their homes to face an uncertain future. The postwar prospects of Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, were no clearer than those of his men. When he left Appomattox, he began a journey that would take him away from a soldier's life in the field and eventually to Lexington, where his talent for leadership would serve him well as president of a small college.

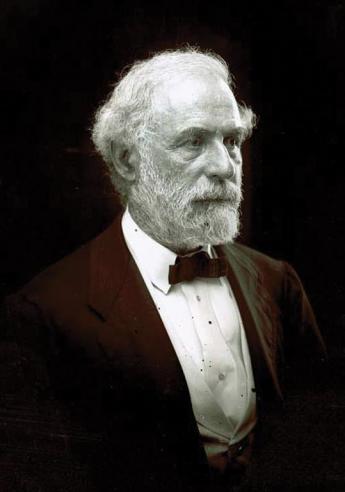

Robert E. Lee after the War

Portrait of Robert E. Lee by Michael Miley, c. 1870

Lee's military career, which had started at West Point many years before, had ended, and his civilian life began when he returned to Richmond and his family on April 15th. For the next two months Lee lived in a city busily rebuilding itself. That summer, he and his family escaped the chaotic atmosphere of the capital city and took up residence at Derwent, a house owned by Elizabeth Randolph Cocke west of Richmond in Powhatan County. There, Lee enjoyed life in the country and considered buying land and living out his remaining years as a farmer. Whatever happened, he had no desire to leave Virginia. "I cannot desert my native state in the hour of her adversity," he remarked to a friend. "I must abide her fortune, and share her fate."

The solitude did not last long. The trustees of Washington College in Lexington, then looking for a new president, decided that Lee was the perfect choice. He had been superintendent of West Point earlier in his military career, and more importantly, he had a very recognizable name in 1865. The college, mired in financial difficulties, needed a prominent person to help raise funds. At first Lee hesitated, but on the advice of friends and family he eventually accepted the position. He wrote to the trustees that he believed, "it is the duty of every citizen, in the present condition of the Country, to do all in his power to aid in the restoration of peace and harmony."

A new life in Lexington

Lee arrived in Lexington in mid-September 1865 and went to work immediately. Over the next five years, Washington College grew physically and financially: the faculty increased in size from four to twenty, enrollment grew from fifty to nearly 400 students, and financial contributions poured in from both southern and northern sources. Lee's personal involvement with many of his students reflected his desire to create a new generation of Americans. In response to the bitterness of a Confederate widow, Lee wrote, "Dismiss from your mind all sectional feeling, and bring [your children] up to be Americans."

Lee's tireless devotion to his duty as president of Washington College eventually took its toll on his health. The outward signs of the heart condition that had plagued him since the Civil War grew more apparent, and in the spring of 1870, on the advice of the faculty, he travelled south on vacation. Less than a month into the next school year, on September 28, 1870, he suffered a massive stroke. Two weeks later, on October 12, Robert E. Lee died in his home on the college campus.

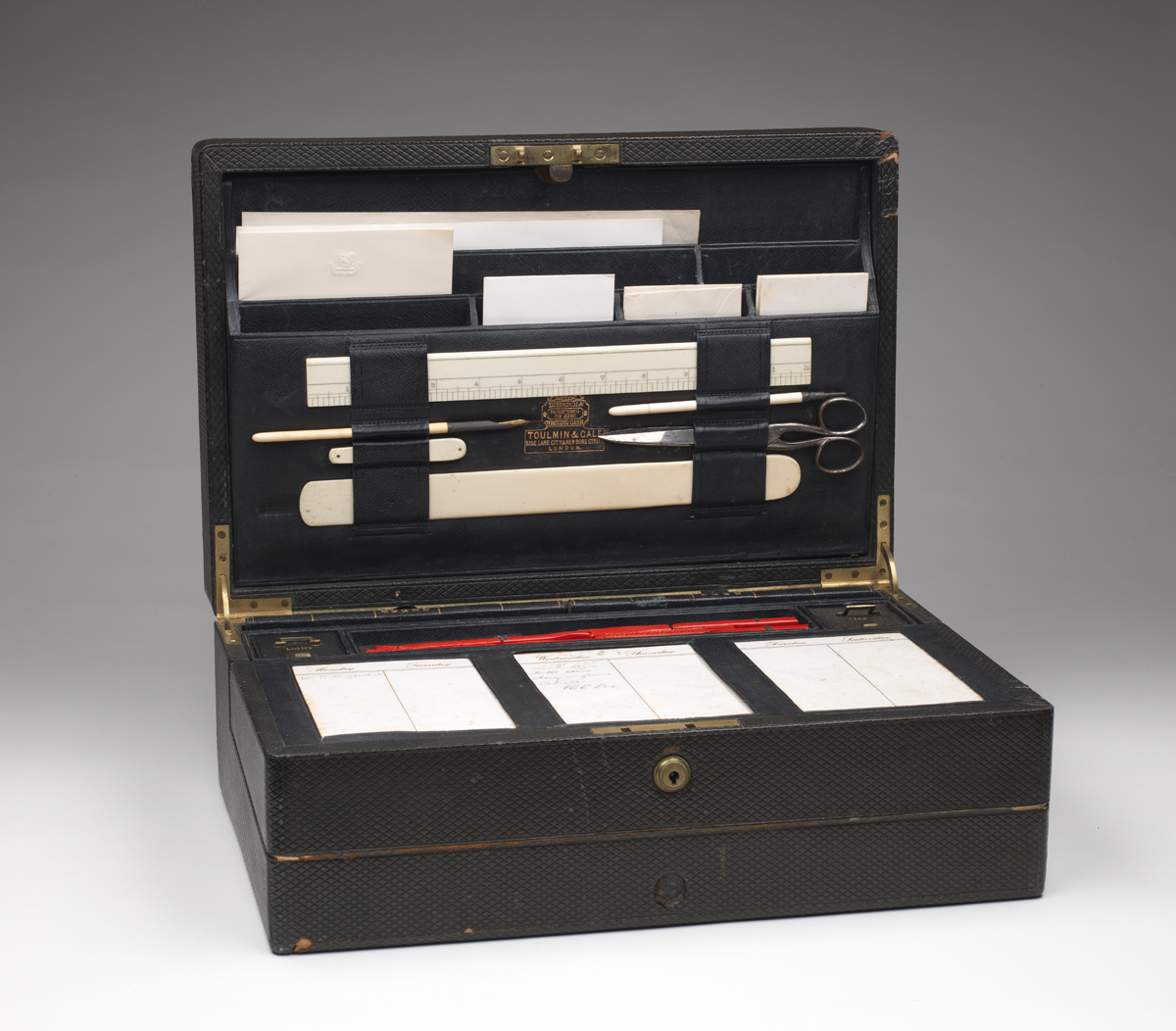

Open lap desk belonging to Robert E. Lee while president of Washington College showing personal documents and tools organized inside.

Lee's lap desk

In December 2005 the Virginia Historical Society acquired from Lee family descendants the portable lap desk that belonged to Lee while he lived in the president's house at Washington College. The desk is currently on display in the long-term exhibition The Story of Virginia. Among the interesting items in the desk is a "cash" book that includes a record, in Lee's hand, of his salary as president of the college. Although a sword might symbolize Robert E. Lee's distinguished military service, the desk represents the final chapter of his life—a period in which he dedicated himself to educating young men and reuniting the country that he had so recently fought against.