For most of history, humans have lived in a four-mile-an-hour world. People traveled only as fast as their feet, their animals, or the wind could carry them. This began to change early in the nineteenth century with the introduction of steam power, but the real changes in this area have occurred over the past century with the development of the gasoline-powered engine.

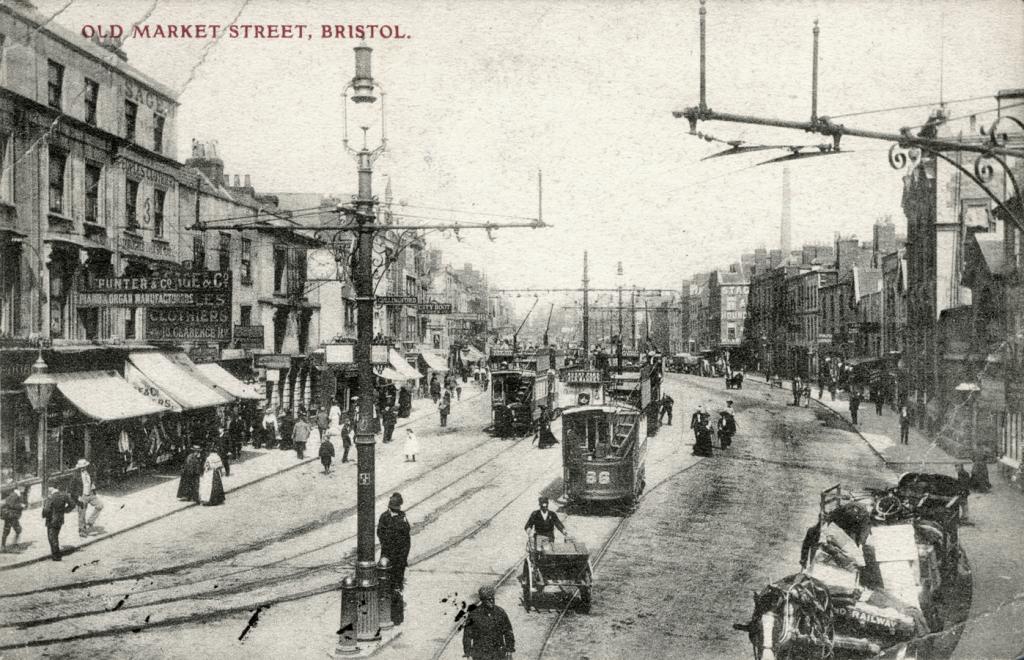

Transportation in Virginia

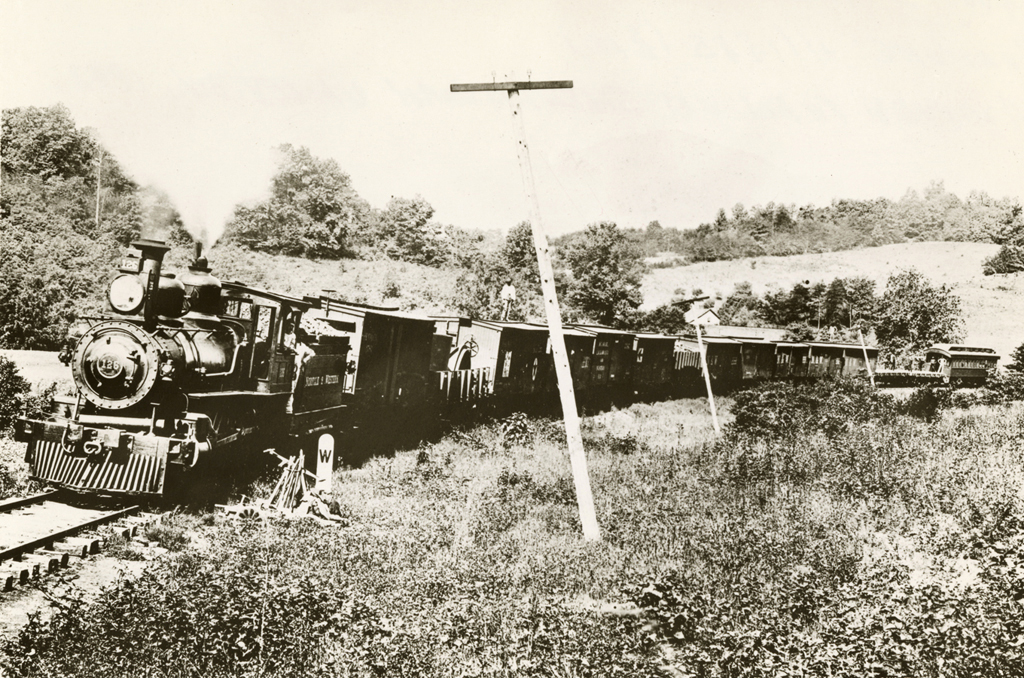

Railroad train, Shenandoah Valley, 1892

Virginia's first railroads were built to facilitate the movement of agricultural products from the Piedmont to cities along the fall line or in the Coastal Plain. Thus, they competed with another form of transportation—the canal. No large-scale systematic rail network developed in Virginia until after the Civil War. At this time, railroads expanded rapidly throughout the commonwealth. Many investors realized the potential profit in Virginia's railroads, especially after the opening of the first coal mine in Tazewell County in 1882.

The Norfolk and Western and Chesapeake and Ohio railroads connected Virginia ports with the vast coalfields in southwestern Virginia and West Virginia. Newport News, a small village until the C&O established its terminus there, grew quickly and became one of the nation's leading ports and shipbuilding centers. Norfolk exported vast amounts of coal and cotton. The railroads also made possible the expansion of Virginia's fledgling tourism industry. By the 1890s, trains were carrying tens of thousands of out-of-state visitors to Luray Caverns, Virginia's beaches, and the western springs.

The coming of the railroad generated excitement and optimism in many small communities. Real estate values climbed, and towns existed on maps long before they existed in reality. Often real growth did occur. Citizens of Big Lick raised $10,000 to induce the proprietors of the Shenandoah Valley Railroad to select their hamlet as the junction point with the Norfolk & Western. In 1882, Big Lick became Roanoke, and within two years its population had grown from 400 to 5,000. More typical, however, was the experience of Big Stone Gap, where speculative investment led to the construction of a 300-room hotel, a streetcar system, a street lighting system, two opera houses, a waterworks, and a 3,000-acre hunting preserve. The Panic of 1893, however, destroyed the dreams of civic boosters in Big Stone Gap and others like them throughout the state.

Changes in transportation also affected life in the cities. The nation's first electric streetcar system was introduced in Richmond in 1888. Streetcar lines connected central cities with the expanding suburbs, while longer lines, called street railroads, carried passengers between cities and outlying communities.

The first automobile appeared on Virginia's streets in Norfolk in 1899. Before Henry Ford's assembly line, automobiles were custom-made in small shops throughout the nation. The first Virginia-made car, the Dawson Car, was built in Basic City (now Waynesboro) in 1901. The Piedmont and the Kline Kar were manufactured in Lynchburg and Richmond respectively.

Automobile ownership increased rapidly during the second decade of the twentieth century. In 1910 there were 2,705 motor vehicles registered in the commonwealth; by 1916 that number had risen to more than 37,000. But a car was only as good as the road system over which it traveled. Road building and maintenance was the responsibility of each locality, so there was a great disparity in the quality of roads. Those areas of the state that provided good roads, such as the Shenandoah Valley, opposed paying taxes to improve roads in other areas. The overall road system was poor enough, however, that in 1921 the Automobile Club of America recommended that motorists traveling from New England to Florida bypass the state of Virginia.

Road building in progress.

Road construction would become an important political issue in Virginia in the 1920s. Although virtually everyone agreed that more and better roads were needed, people disagreed over how to finance them. Some wanted the state to authorize highway bonds to finance construction. In effect, this would mean borrowing money. Others opposed highway bonds and wanted to construct roads by using existing state revenues only. This would mean slower growth but would keep the state out of debt. The leader of this group was Harry F. Byrd, a state senator, newspaper owner, and apple orchardist from Winchester. Because of his leadership, a 1922 state referendum on highway bonds was defeated by a large margin. Virginia's roads would be financed through existing revenues through a plan that became known as "pay as you go."

The Great Depression affected Virginia tremendously, but so too did Byrd's conservatism. He became a U.S. senator in 1933 and served as the head of the political organization that dominated the state over the next three decades. Byrd supported road construction, even to the extent that before 1936 the only relief money the state distributed was through its highway department. Men were put to work, but the most significant result of Virginia's relief efforts was the construction of new roads. As the number of paved roads increased, so did the number of services related to the automobile. Service stations, motor courts, and drive-in restaurants all sprang up, and destinations such as Colonial Williamsburg attracted motorists and their families.

By the late 1940s, busses were beginning to replace streetcars in the cities. With the rapid expansion of the suburbs after World War II, busses proved to be more practical than track-bound streetcars. The last Richmond streetcar made its final run in 1949, sixty-one years after the first electric streetcar appeared on its streets.

In 1956, the U.S. Congress passed the Interstate Highway Act. This law authorized the construction of what would become 42,500 miles of "superhighways," or limited access highways, 1,070 miles of which would be in Virginia. Virginia's first superhighway was the Emporia bypass, a portion of Interstate 95 that opened to traffic on September 8, 1959. By making travel easier, the interstate highway system also made commuting easier, thus augmenting the growth of suburbs.

By the 1980s many businesses followed workers and retail stores out of the central cities and relocated in the suburbs. In doing so, they redefined suburbia. Many of today's suburbs are more than just residential areas; they are also shopping and business centers. "Exurbs," such as Fairfax County's Tyson's Corner, provide many of the services of a traditional central city.

Teachers: Visit Teaching with Photographs for questions to ask your students about Transporation in Virginia.