The museum world is brimming with tales of curators sleuthing to discover intriguing stories that lay beneath the surface of artifacts. Perhaps no other form of object has captured this fascination more than paintings, which are often the subject of intense scientific scrutiny as conservators—highly trained specialists tasked with preserving collections—work with scholars to reveal these discoveries. One of the VMHC’s most important works of art was recently the subject of such an investigation.

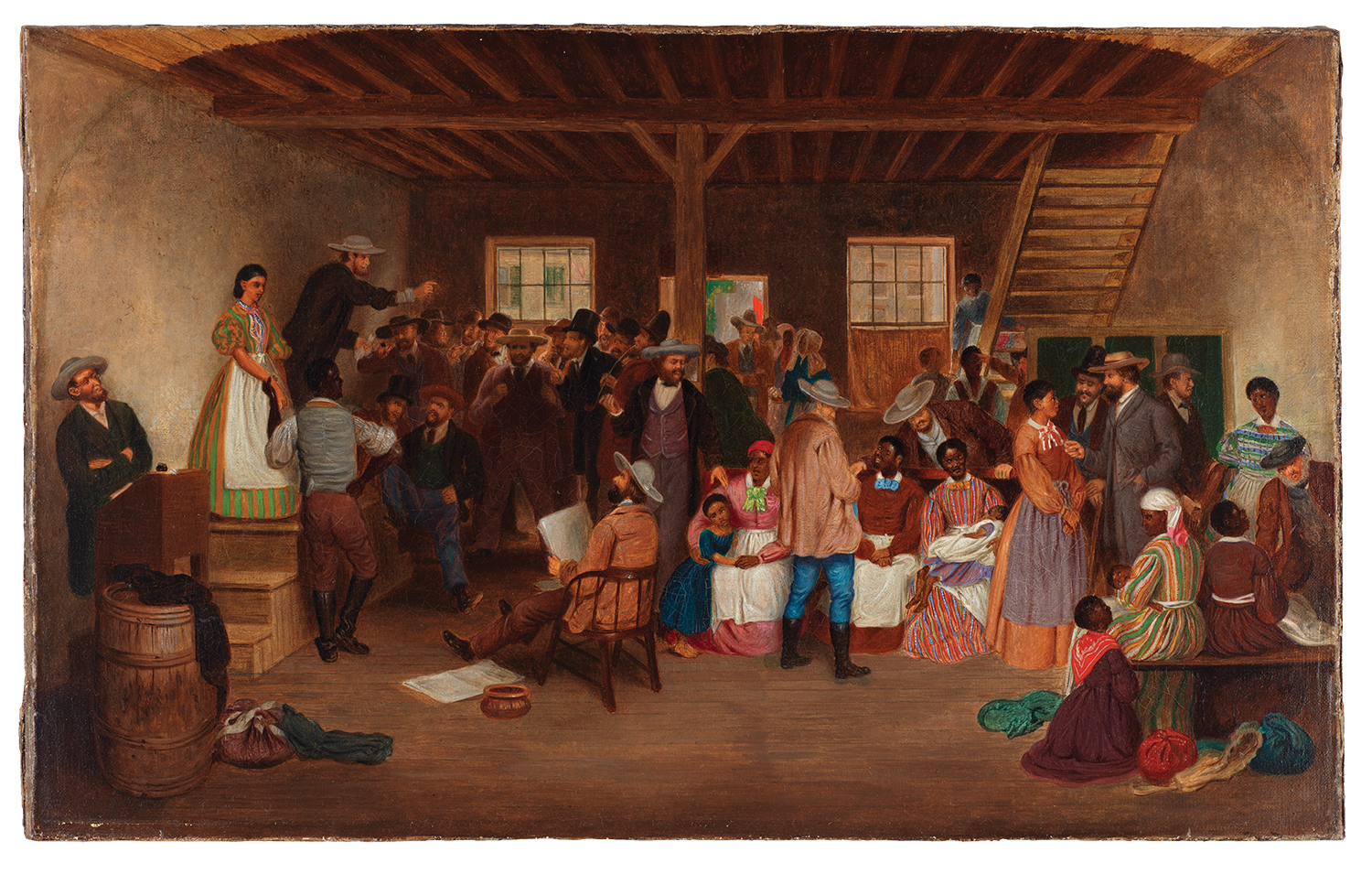

English artist LeFevre J. Cranstone’s 1862 painting, Slave Auction, Virginia, was purchased by the Virginia Historical Society in 1991, one of two renditions made by the artist—the other resides at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas. There are significant differences between the two compositions, including elements that make the Crystal Bridges rendering much more provocative. This change in the artist’s perspective over time on such a politically and emotionally charged subject like slavery has long been a point of interest for art historians researching Cranstone. In 2019, infrared imaging performed at the Dallas Museum of Art revealed that the Crystal Bridges rendering had an intricate underdrawing with a grid, raising the question as to whether the VMHC work had a similar treatment and, if so, if it might reveal clues to determine the order in which the works were executed.