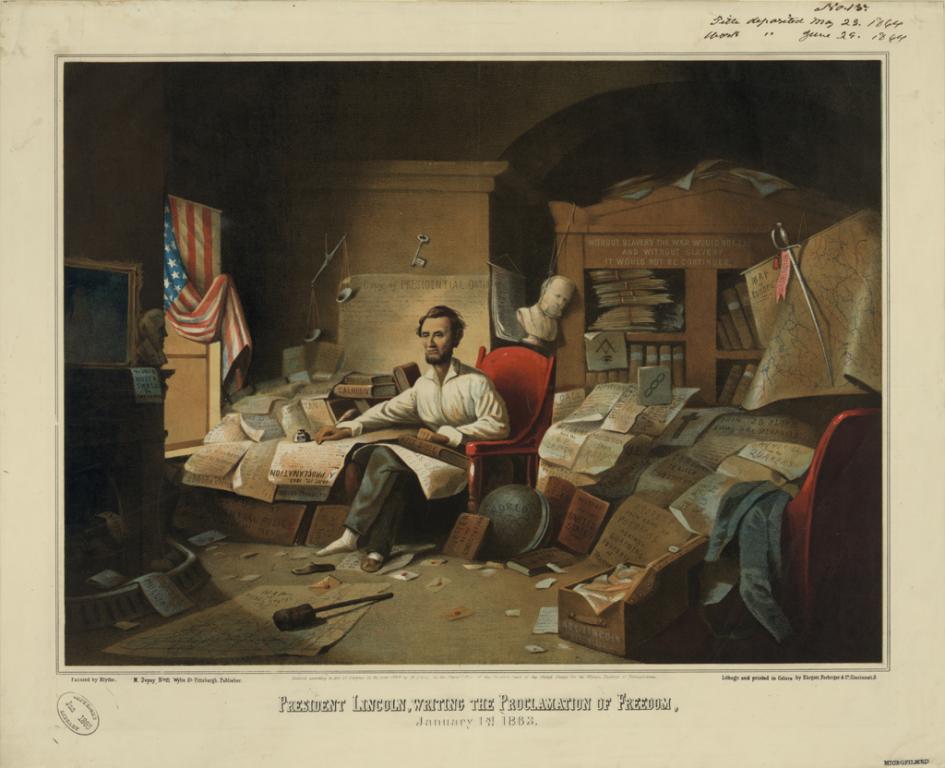

The Emancipation Proclamation

Lack of military successes, growing pressure from radical elements of his party, and fears that France or Great Britain might recognize the Confederacy plagued Abraham Lincoln during the summer of 1862. On September 22, he issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation declaring all slaves in areas not returned to U.S. control by January 1, 1863, "then, thenceforward, and forever free." The proclamation exempted the loyal slave states, areas then occupied by United States forces, and the forty-eight counties of Virginia in the process of forming West Virginia. The transformation of war aims to include ending slavery elicited contempt among Confederates as well as some resistance within the U.S. Army. The proclamation turned foreign opinion against the Confederacy and encouraged more slaves to escape to United States lines and enlist in the U.S. Army.

Lincoln worried that freeing the enslaved might aggravate northerners who had tired of the human and material costs of the war; he hoped it would inspire many of them. Given a noble cause, they might regain a resolve that would match that of their enemy. Many in fact applauded him. This laudatory commentary was drawn by a Pittsburgh artist.

- As Lincoln writes, his hand is placed on a Bible that rests on a copy of the U.S. Constitution—the sources of his inspiration.

- The scales of justice hang badly out of balance. Also on the wall hangs a key—perhaps to open locks and free the enslaved. A copy of the presidential oath reminds Lincoln of his pledge to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.

- A bust of Lincoln’s ineffective predecessor, James Buchanan, who allowed the southern states to secede, hangs by its neck.

- A bust of Andrew Jackson—a strong unionist—holds down a paper with his words: “The Union must and shall be preserved.”

- A map of the rebellious states is held in place by Lincoln’s heavy railsplitter’s maul—to suggest that Lincoln will hold the southern states in the United States.

- A map of Europe, with the sword of isolationist president George Washington hanging over it, reminds viewers that foreign intervention is never wanted and that the nation is vulnerable when divided.