Why was Richmond made the Confederate capital and how did that status change life there?

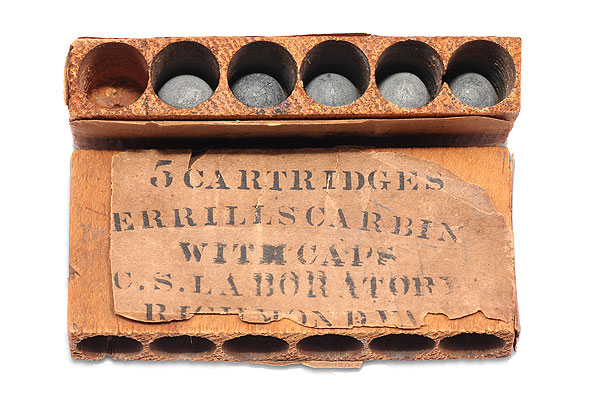

Once Virginia seceded, the Confederate government moved the capital to Richmond, the South’s second-largest city. The move served to solidify the state of Virginia’s new Confederate identity and to sanctify the rebellion by associating it with the American Revolution. Most important were Virginia’s hundreds of factories, whose output nearly equaled that of the rest of the Confederacy.

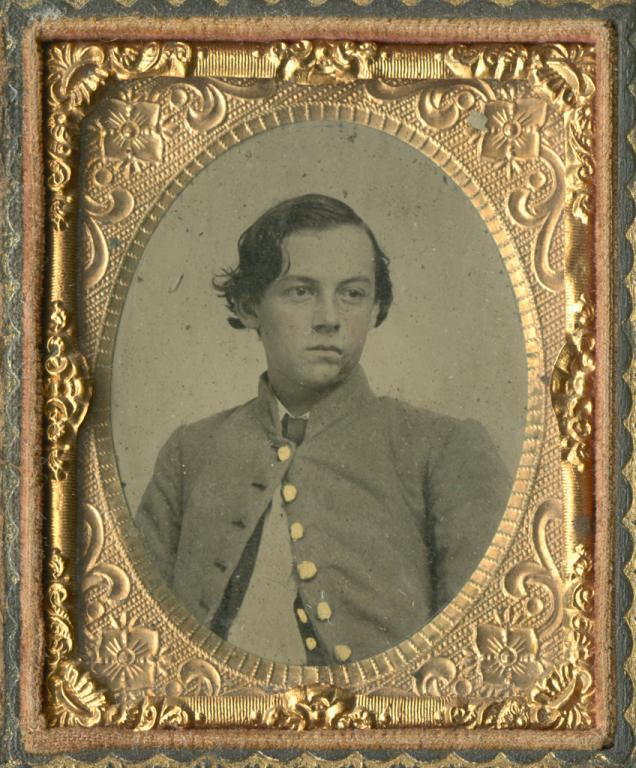

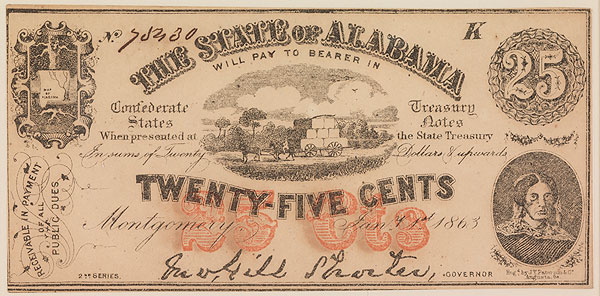

As the capital of the Confederacy, the city’s population soon tripled. An influx of troops, profiteers, and refugees, followed by the wounded, sick, and captives from the battlefront, brought shortages of provisions, skyrocketing inflation, and the establishment of multiple hospitals and prisons.

The heightened status of Richmond caused both United States and Confederate armies to focus their efforts on the capture or defense of that city. Northerners cheered the U.S. Army forward in Virginia with the cry, "On to Richmond."