Clementina Rind was Virginia’s first female printer and newspaper publisher, publishing important official documents for the early colony, as well as the Virginia Gazette. Her management of her deceased husband’s printing office in Williamsburg was incredibly successful, and through her newspaper she helped shape the public consciousness on the eve of the American Revolution. Two artifacts in the VMHC collections offer a glimpse not only into the life of Clementina but also into an important, but often overlooked, aspect of colonial history and early literary endeavors: the role of female printers.

Clementina Rind

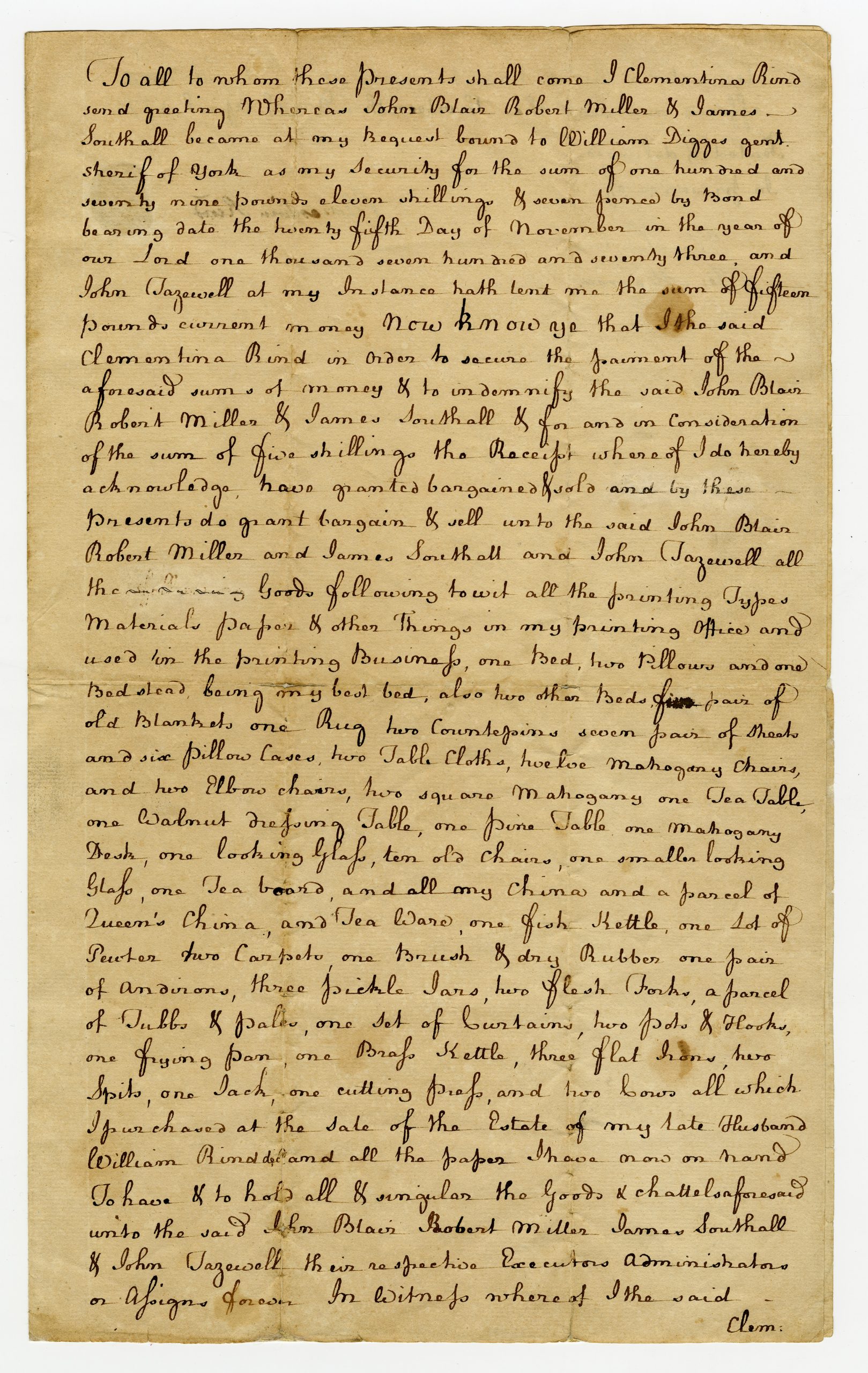

Deed, 1774 April 13, to John Blair, Robert Miller, James Southall, and John Tazewell. (Mss2 R4715 a 1)

We know little about Clementina's early years. She may have been a native of Maryland, but no record of her birth or marriage survives. Her husband, William Rind, was born in Annapolis in 1733 and was an apprentice there to printer Jonas Green. After a seven-year partnership with Green, the two suspended publication of the Maryland Gazette in October 1765 to protest the Stamp Act. Shortly after, William accepted the invitation of a group of Virginians, including Thomas Jefferson, to publish a paper in Williamsburg.

The first issue of William’s Virginia Gazette appeared on May 16, 1766, under the motto: "Open to ALL PARTIES, but Influenced by NONE." The newspaper and bookshop operated out of the present Ludwell-Paradise House. Shortly after, the assembly chose William as public printer for the colony, and in spite of escalating paper costs, the business prospered and its reputation grew.

In August 1773, a week after her husband's death, Clementina Rind took over the editorship and business management of the press without missing a single issue. When William died, he left behind outstanding debts that put Clementina and her family at risk of losing their possessions. In order to keep ownership of the press and related printing equipment, Clementina purchased the items at a sale on six month’s credit. When payment time came, she entered into a deed of trust with four men in the colony – including Williamsburg’s mayor – promising the contents of her printing office and other personal property to those men as security for two loans, as evidenced in this deed from April 13, 1774, to John Blair, Robert Miller, James Southall, and John Tazewell.

As editor, she was careful to preserve the integrity pledged in the press’s motto. Clementina ran her newspaper in some senses like a literary journal, featuring poetry, essays, and articles alongside the standard reports of domestic affairs, shipping news, local advertisements, and stories from Europe. These items revealed her interests in scientific developments and educational opportunities, particularly with regard to the College of William and Mary. It is clear that Clementina valued women as readers of her paper, for it included poetic tributes to women in acrostic or rebus form, prose, and news reporting with a feminine slant. She also included vignettes of life in European high society, in rural England, and in the other colonies.

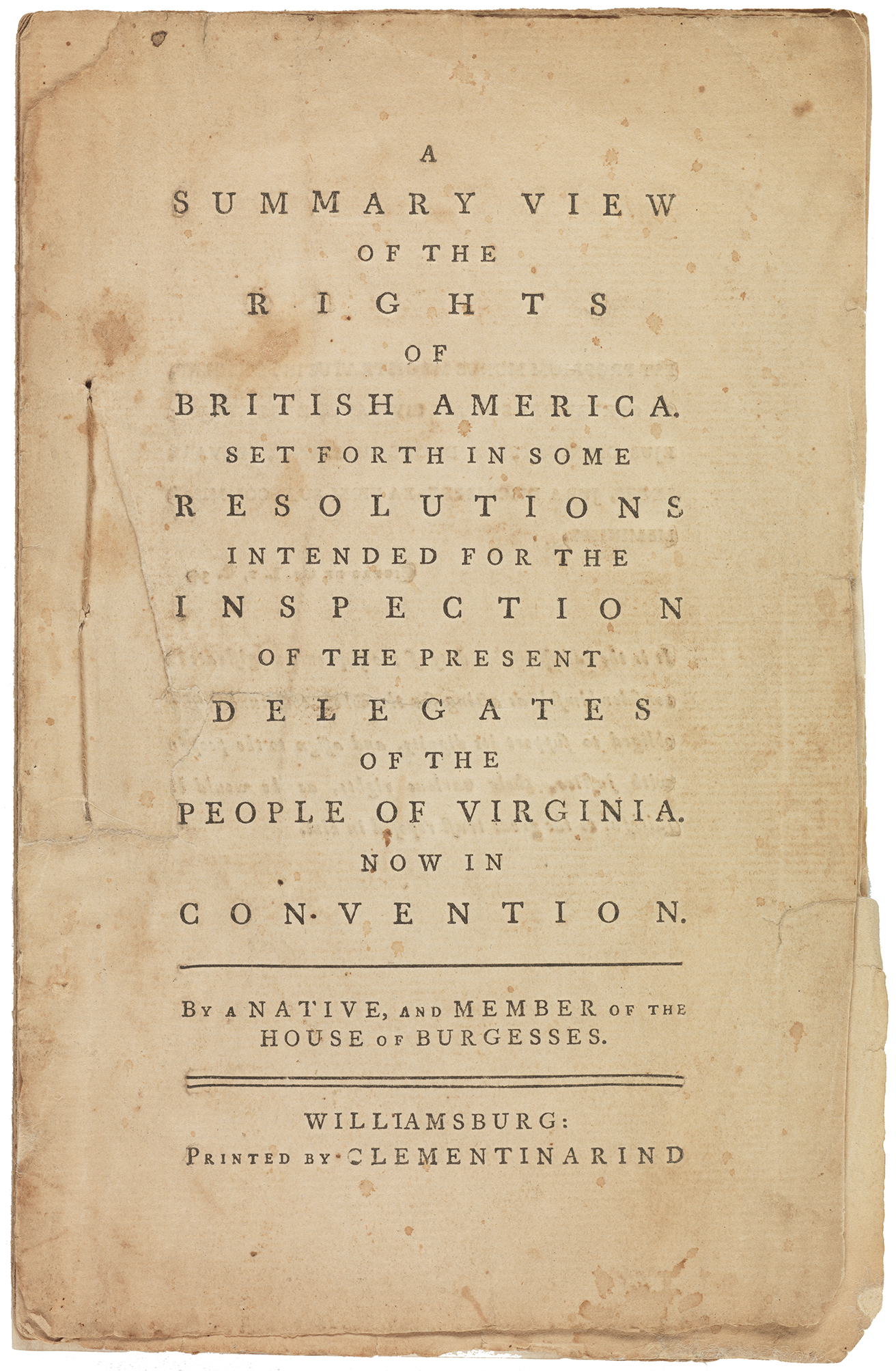

A summary view of the rights of British America. Set forth in some resolutions intended for the inspection of the present delegates of the people of Virginia. Now in convention. By a native, and member of the House of Burgesses. (Rare E211 .J45 1774)

Aside from the Virginia Gazette and government materials, there are only a handful of other publications that have been attributed to the printing press of Clementina Rind. One of those publications was the first edition of Thomas Jefferson's A Summary View of the Rights of British America, which Clementina published just after Peyton Randolph read it aloud in his home to a gathering of Virginia patriots. George Washington was among the first to purchase a copy, writing in his diary that it cost him three shillings and ninepence. The tract brought Jefferson widespread attention as an early advocate for American independence; it was reprinted in Philadelphia and London, and its importance has been described as "second only to the Declaration of Independence." Clementina's publication of this document– and the increasingly patriotic lean of her Virginia Gazette – illustrates that women were also active participants in the imperial resistance throughout the colonies.

Clementina’s bid for public favor was so well received that she expanded her printing program. In May 1774, the House of Burgesses appointed her public printer in her own right, and it continued to give her press all the public business in spite of competing bids from Purdie and Dixon, publishers of a rival Virginia Gazette.

In August of that year, she became ill and found it difficult to collect payments. She died in Williamsburg a month later and was likely buried beside her husband at Bruton Parish Church. Although Clementina Rind lived only about thirty-four years, her brief obituary read, "a Lady of singular Merit, and universally esteemed." A number of poetic eulogies and a formal elegy of 150 lines expressed admiration and respect for her varied interests, literary talent, and sound critical judgment.