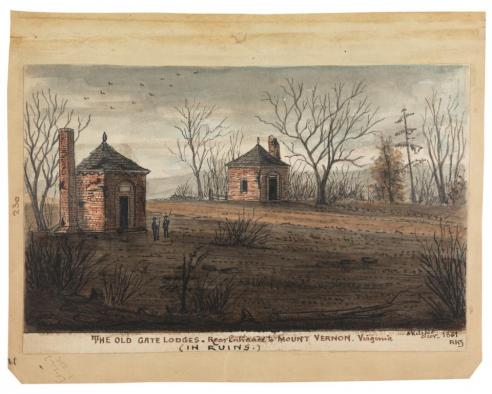

Through the words he wrote, the maps he drew, and the watercolors he painted, Robert Knox Sneden takes us to the front lines of the Civil War. In chilling detail, Sneden describes his harrowing experience as a Union soldier, mapmaker, and prisoner of war. His 5,000-page personal memoir, containing detailed watercolors, maps, and drawings of Civil War battlefields, landscapes, and prisons are the basis of a permanent exhibition at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture (Virginia Historical Society), a book, and a traveling exhibition.

Through the words he wrote, the maps he drew, and the watercolors he painted, Robert Knox Sneden takes us to the front lines of the Civil War. In chilling detail, Sneden describes his harrowing experience as a Union soldier, mapmaker, and prisoner of war. His 5,000-page personal memoir, containing detailed watercolors, maps, and drawings of Civil War battlefields, landscapes, and prisons are the basis of a permanent exhibition at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture (Virginia Historical Society), a book, and a traveling exhibition.

Discovering the Sneden Collection

One afternoon in the fall of 1994, two men came into the front lobby of the Virginia Historical Society with something to show Dr. James C. Kelly, the society’s assistant director for museums. Unsolicited requests to come in and show objects to staff members are common occurrences at the museum. Sometimes they result in desirable additions to the collection, sometimes not. Kelly escorted the men to the rare book room where they chatted for a few minutes. Then one of them opened the suitcase. It took little time for Kelly to realize the contents were extraordinary. He excused himself and went across the hall to bring in the historical society’s director, Charles F. Bryan, Jr. After exchanging pleasantries, Bryan watched as one of the men began turning the leaves of the albums. He was stunned to see page after page of detailed watercolor sketches and intricate, hand-drawn maps. In all, the four albums contained a remarkable collection of more than 400 images, most of which portrayed views of Virginia during the Civil War, though some depicted Confederate prison camps, including the most notorious at Andersonville, Georgia. They were all created by a Union soldier named Robert Knox Sneden, a map maker in the Army of the Potomac.

Sneden was a mystery. The man with the suitcase said the albums had been in his family’s Connecticut bank vault for sixty years. He had approached the other visitor, a dealer in southern artwork, to help him sell the collection for a substantial sum. Despite limited information about the artist, and despite the large price tag, Bryan and Kelly knew the drawings were important. Bryan also knew the society did not have the resources to purchase them. Fortunately, two benefactors came forward to make the purchase possible, and the Sneden images now form one of the premier treasures in the historical society’s collections.

Kelly then began searching for information about the elusive artist. The more the historical society’s staff studied the drawings, the more compelling they seemed. They soon discovered a few of the watercolors resembled engravings that appeared in the monumental series, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, published by the Century Company in the 1880s. Sneden had contributed three dozen images to the series. Then he dropped from sight. So the Virginia Historical Society had found the missing Sneden collection, or so it thought. The real surprise did not come for three more years, when Kelly’s research led him to a Sneden descendant. This man, Kelly was astonished to learn, owned another collection consisting of thousands of pages of memoir and approximately 500 more watercolors and maps that were housed in a rented storage bin near Tucson, Arizona. Through a complicated arrangement, the historical society acquired this collection, too. Only then, with the artist’s own account of his harrowing experiences under fire in the field and in Confederate prisons, did the extraordinary story of Robert Sneden fully come to light.

Kelly then began searching for information about the elusive artist. The more the historical society’s staff studied the drawings, the more compelling they seemed. They soon discovered a few of the watercolors resembled engravings that appeared in the monumental series, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, published by the Century Company in the 1880s. Sneden had contributed three dozen images to the series. Then he dropped from sight. So the Virginia Historical Society had found the missing Sneden collection, or so it thought. The real surprise did not come for three more years, when Kelly’s research led him to a Sneden descendant. This man, Kelly was astonished to learn, owned another collection consisting of thousands of pages of memoir and approximately 500 more watercolors and maps that were housed in a rented storage bin near Tucson, Arizona. Through a complicated arrangement, the historical society acquired this collection, too. Only then, with the artist’s own account of his harrowing experiences under fire in the field and in Confederate prisons, did the extraordinary story of Robert Sneden fully come to light.

Significance of the Sneden Collection

The discovery of the Robert K. Sneden collection brings to light a rich, new, and entirely unexplored Civil War resource of the first rank. The graphic materials – about 1,000 watercolors, sketches, diagrams, maps, and landscapes – constitute perhaps the largest collection of soldier art to survive the war. It is not just the art, however, that gives the collection its distinction. The pictures that Sneden painted in words carry at least equal weight for enriching our understanding of America’s great national trial.

Sneden the memoirist does not change our interpretation of Civil War battles or leaders, but Sneden the storyteller will mesmerize us with the power of his narrative. It is the story of a soldier who saw first-hand some of the most dramatic events of the war. The chaos of battle is nowhere better portrayed than in his accounts of the Peninsula and Seven Days’ campaigns of 1862 when General George McClellan threw away a golden chance to end the war at an early stage. Even more compelling are Sneden’s vivid passages that describe with the passion of the eyewitness the horrific conditions of prison life in the South during the harrowing year he spent as a prisoner of war, most of that time at the infamous Andersonville camp in Georgia.

Sneden the memoirist does not change our interpretation of Civil War battles or leaders, but Sneden the storyteller will mesmerize us with the power of his narrative. It is the story of a soldier who saw first-hand some of the most dramatic events of the war. The chaos of battle is nowhere better portrayed than in his accounts of the Peninsula and Seven Days’ campaigns of 1862 when General George McClellan threw away a golden chance to end the war at an early stage. Even more compelling are Sneden’s vivid passages that describe with the passion of the eyewitness the horrific conditions of prison life in the South during the harrowing year he spent as a prisoner of war, most of that time at the infamous Andersonville camp in Georgia.

Sneden could create this dramatic account because of his narrative talent and because of the sources he had at hand when he wrote. He did not write from memory alone, but with the aid of extensive diaries that he kept as a mapmaker before his capture and short-hand diaries he surreptitiously wrote as a prisoner of war and smuggled out of the Confederacy on his release. Using these resources and casting his memoir in diary form, he gives his story an immediacy that other memoirs lack.

Sneden’s descriptive power is especially apparent in the prison sequences, with a dramatic evocation of the helplessness of living under the constant threat of violence, deprivation, disease, and despair. From his capture by John Singleton Mosby to the tedium of prison life, to the dramatic execution of the “raiders” at Andersonville by fellow prisoners, to his secret sketching of Confederate forts while on parole, Sneden the master storyteller grips the reader with the fervor of one who had endured much and burned with the desire to tell the world of his ordeal.

Sneden's Wartime Dispatch Case

In the fall of 2017, the Virginia Museum of History & Culture further enhanced its incomparable Sneden collection with the acquisition of a wartime courier dispatch case that belonged to Sneden. This artifact, which bears Sneden's name and his handwritten instructions on what to do with the case if found after his death, represents the only personal possession of his he had with him during the Civil War.