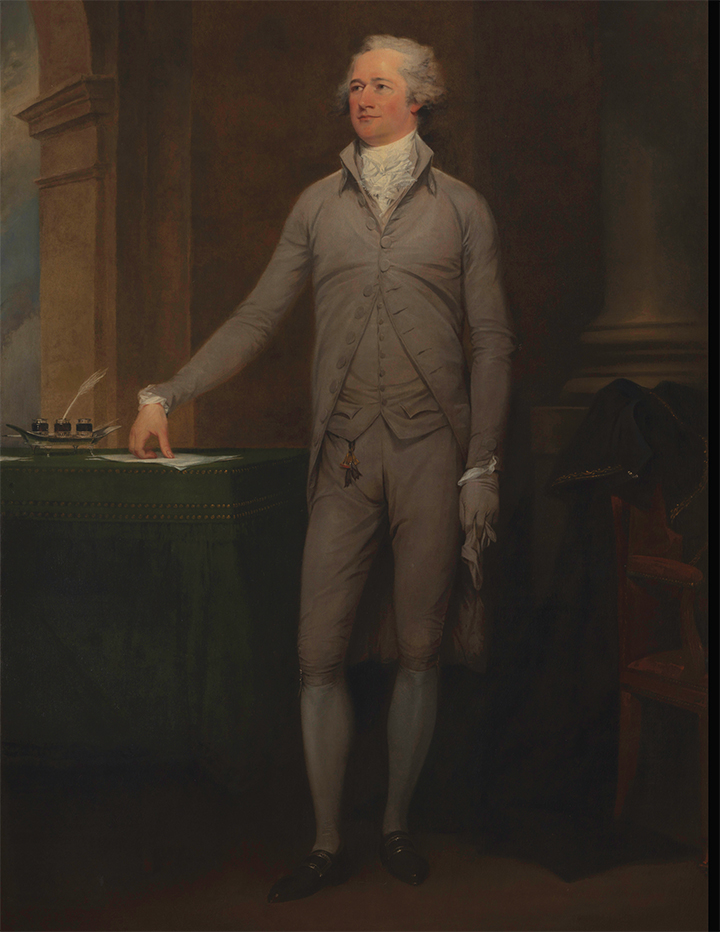

Founding Frenemies: Hamilton & The Virginians, on exhibition at the VMHC in 2019, examined how critically important relationships between Alexander Hamilton and three Virginians shaped the character of the United States, its founding institutions, and patterns of civil discourse that are still felt today. The protagonists in Founding Frenemies were four of the Founding Fathers. George Washington was Hamilton’s greatest friend and greatest supporter. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were two of Hamilton’s greatest political enemies. The exhibition was inspired by the content of the popular Broadway production, Hamilton: An American Musical. Ten songs from the musical are brought to life through rare artifacts.

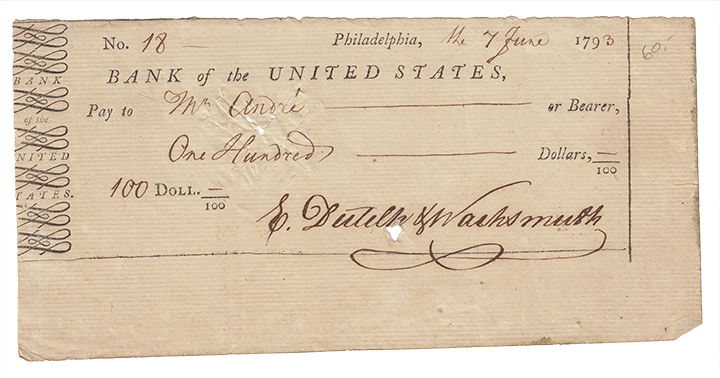

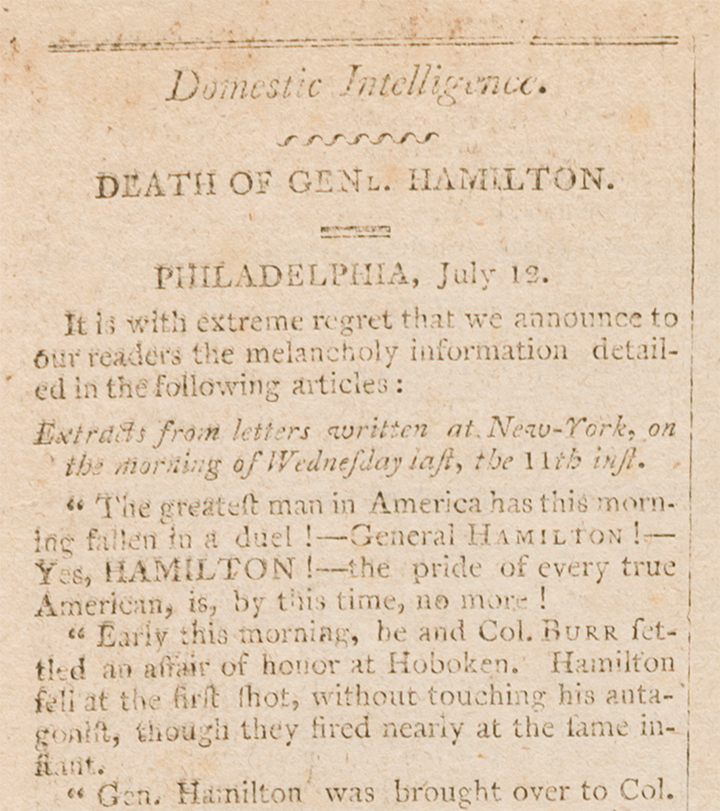

Founding Frenemies opened when a traveling production of Hamilton came to Richmond and Norfolk, bringing heavy publicity to the story. But, regardless of the popularity of the Hamilton story today, there is good reason to present an exhibition about him. Much of his story involves Virginians. Among the millions of objects in the museum’s collection are letters by Hamilton that relate to both the Revolutionary War and his accomplishments as secretary of the treasury; letters by his Virginia friends and foes that illustrate the immense political divide in the 1790s; and period books and newspapers that bring to life such major episodes in the Hamilton story as his report on the national bank, his “observations” regarding the Maria Reynolds scandal, and his defense of the Treasury’s policy with Dutch loans.