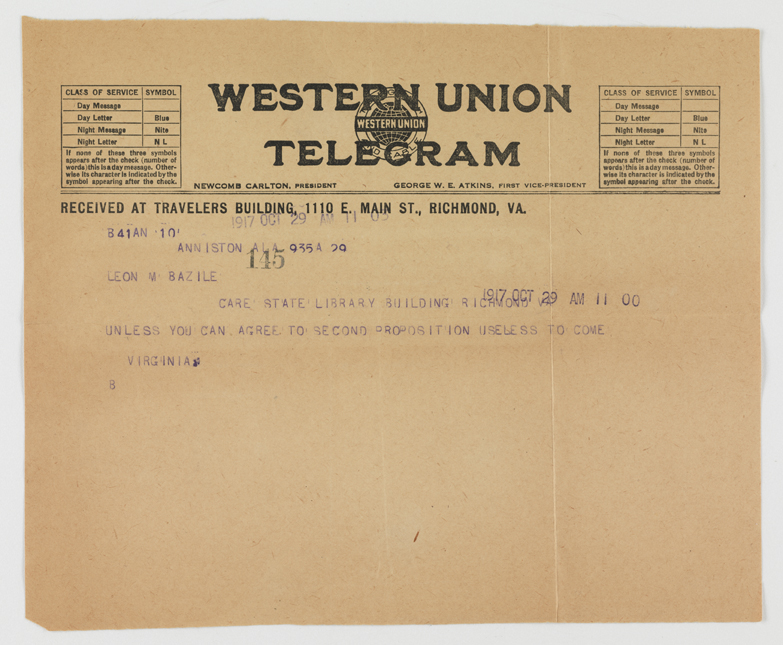

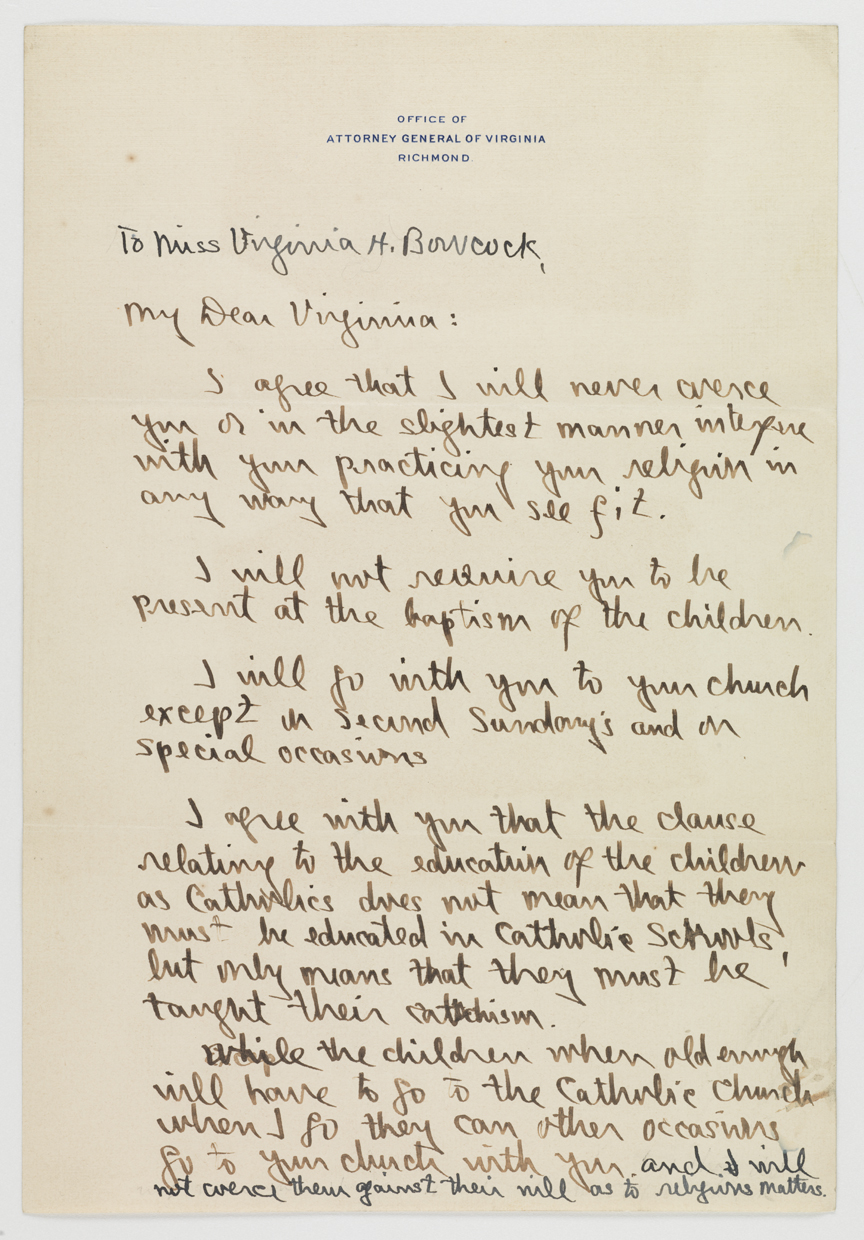

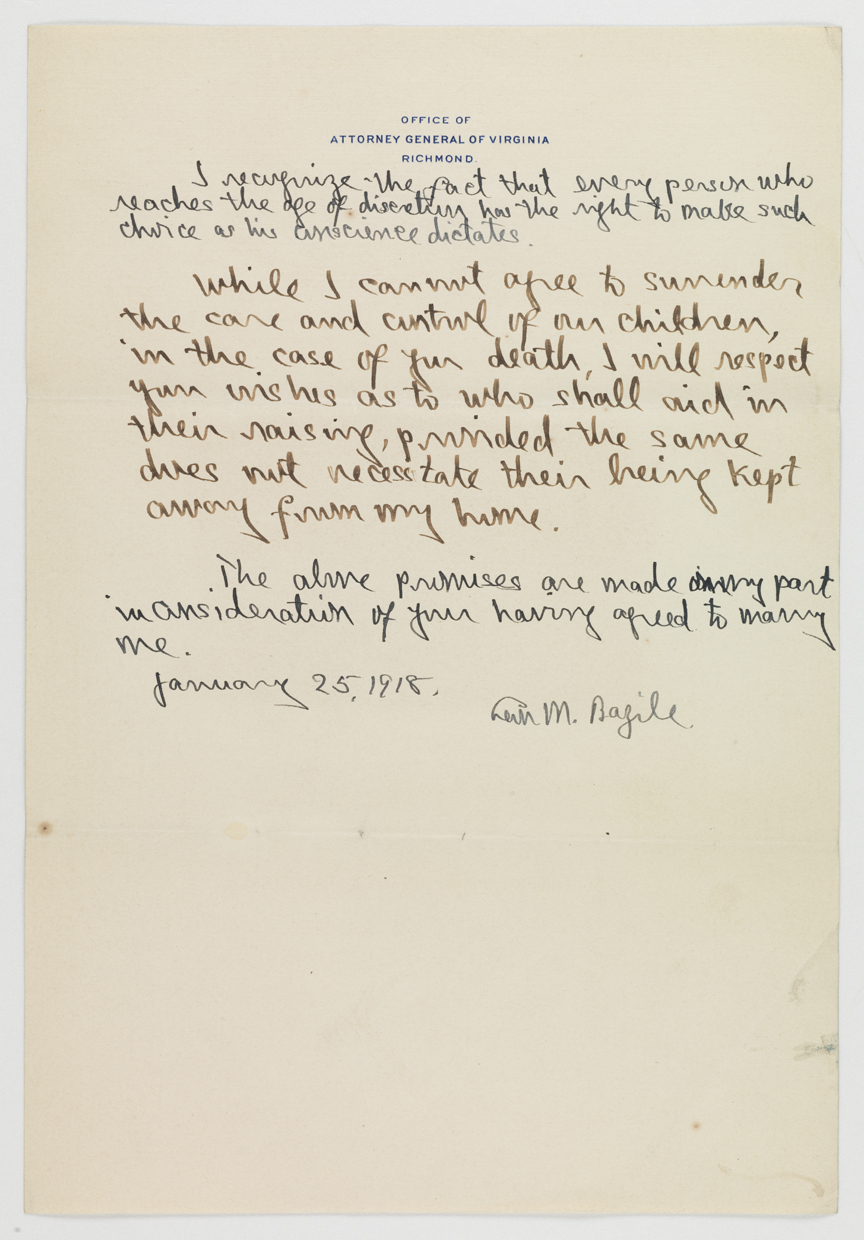

Leon Maurice Nelson Bazile was a lawyer, legislator, and judge of Virginia's Fifteenth Judicial Circuit from 1941–1965. A native and lifelong resident of Hanover County, Bazile was also a student of local history, especially that of St. Martin's Parish, the western-most section of the county. Contained within the Leon M. (Leon Maurice) Bazile Papers, 1826–1967 in the VMHC collections are a series of letters between Bazile and his future wife, Virginia Hamilton Bowcock. The two began their courtship in early 1917. At the time, Bazile was a twenty-six-year-old lawyer working in the attorney general’s office in Richmond. Bowcock, as her letters reveal, was smart, serious, and devoted to her church work. She taught Sunday school and at one point had considered becoming a missionary. Her devotion must have been attractive to Bazile, who also was deeply religious. Their courtship moved along quickly.

Leon visited Virginia at her home in Anniston, Alabama, and upon returning wrote of his love and his desire to be married. Virginia, however, saw things differently. It was clear that she was as much in love as he but could not consider marriage. She urged Leon to forget about her.

He was distraught. After beginning several letters between June 11 and June 23, Leon finally wrote: “I have delayed writing to you not because I have failed to think of you, for scarcely a conscious moment has passed me in which I did not think of you, but because I have been trying to think of some way in which to solve the one Problem, the correct solution of which means more to me than any question I have had to face in the past.”