1877 to 1924

A New Virginia

In the early twentieth century, the nation’s economy was becoming more industrialized and its population more urbanized. The hope in Virginia was that the industrialization could lift the defeated region into recovery and to its former national stature, as part of a New South. Railroad lines across the state made development feasible. Northerners and Europeans looked to invest. A New Virginia began to emerge.

The Railroad Industry

A revitalized railroad industry built locomotives in Richmond and in Roanoke. The iron industry that had lured the Confederate capital to Richmond was revived after the war by railroad manufacturing. In 1887, Richmond Locomotive Works grew out of Tredegar Iron Works. It produced some 4,500 steam engines, which were shipped across America, to Europe, Asia, and the South Pacific. In 1901, the works merged with others to form the American Locomotive Company, which continued production in Richmond until 1927.

Railroads were critical to Virginia’s postwar economic revival. Not only did Virginia factories build locomotives, but railroad lines also carried coal, lumber, and tourists to new markets. John Skelton Williams of Richmond looked beyond the state to link Virginia with Florida by rail and thereby create additional commerce and jobs. The line he built was so flat and straight that it was called an “air line” railway.

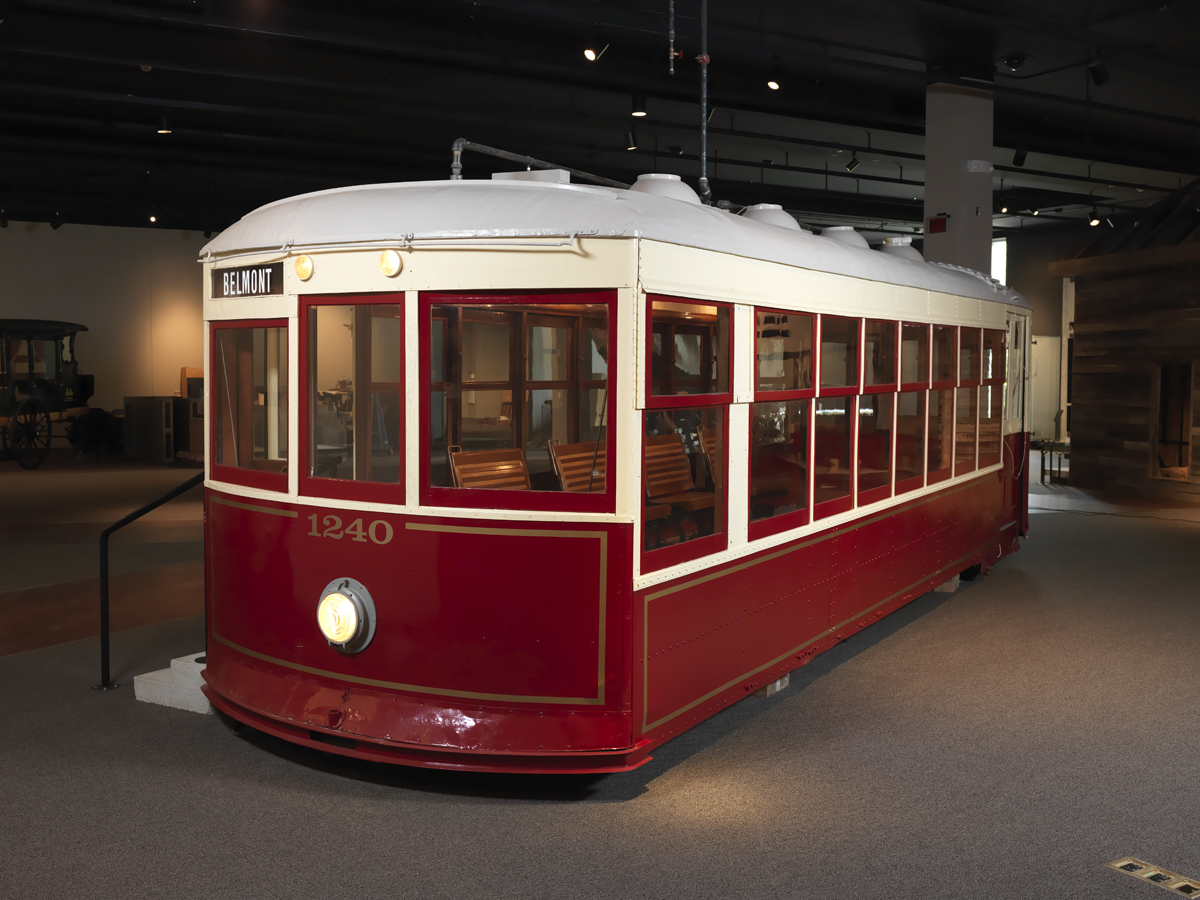

The Streetcar: Modernity and Mobility

Streetcars became a symbol of modern technology in Virginia in May 1888 when Richmond became the first city in the world to introduce a large-scale, fully operational electric streetcar system. Initially, streetcars were pulled by horses along steel rails that ran down the middle of streets. In Richmond, Frank Sprague of New York developed a self-propelled streetcar by creating a central generating station that provided electricity to the system. Streetcars were connected to this power source with long poles, called trolleys, that extended from the car to wires that ran overhead. The twelve-mile network of tracks extended beyond the city limits, facilitating growth and allowing for the development of suburban communities, particularly west and north of the Richmond.

Coal

The 1873 discovery of vast high-grade coal fields transformed southwest Virginia into a booming, industrialized area. Steam locomotives––powered by coal––carried the products of the mines to Norfolk and Newport News for export worldwide. Coal mining is extremely dangerous. Hazards include suffocation, gas poisoning, roof collapse, gas explosions, and such debilitating chronic diseases as black lung.

Cigarette Capital of the World

Although the production of twist chewing tobacco and snuff continued, a new demand for pipes and cigars revitalized Virginia’s postwar economy. By 1880, Richmond and Petersburg produced a million pounds of smoking tobacco per year. With the introduction of bright leaf tobacco, cigarette usage increased from 14 to 200 million Americans. Richmond became the cigarette capital of the world.

By 1900, one-half of the work force of Richmond and Petersburg was producing tobacco for pipes and cigars. By 1910, production totaled 12,000 brands of plug, twist, and fine-cut chewing tobacco; 7,000 brands of smoking tobacco; 3,600 brands of snuff; and 2,000 brands of cigarettes, cigarros, and cheroots. Consolidation and marketing eventually reduced the numbers to a few brands nationally.

Electricity and the Rise of Mass Media

Although Virginia’s largest cities were using electricity by the end of the nineteenth century, some rural areas were not electrified until after World War II. The state’s first large-scale supply of electricity was made available in 1909 by the investor-owned Virginia Railway and Power Company—renamed the Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO) in 1925. During the Great Depression, the federal government’s creation of the Rural Electrification Administration helped Virginians establish local electric cooperatives that improved living standards in the countryside.

The wireless transmission of electromagnetic signals made radio the first form of mass media to compete with newspapers. All Virginians—rich and poor, literate or not—could be reached. Beginning in the 1920s, radio created a culture of mass-consumed news and entertainment that continues to this day.

Pay-As-You-Go

In 1923, Virginia farmers, businessmen, and tourists were driving cars and trucks on inadequate, mostly dirt roads. Rather than sell bonds to finance 3,500 miles of new roads and thereby plunge Virginia into debt, state senator Harry F. Byrd insisted on a “pay-as-you-go” approach––a three-cent-a-gallon tax on gasoline to shift the cost to the people who used the roads. Byrd’s fiscal conservatism resonated in Virginia, and it survives today.