In Jefferson’s letter to a friend and supporter, he reports that twenty-five ballots have been taken without resolution. Jefferson had received 73 electoral votes to defeat Adams, but Jefferson’s vice-presidential running mate, Aaron Burr, also received 73 electoral votes—and Burr attempted to steal the victory and become president himself. On the 36th ballot, Jefferson was elected. The reason was that his arch political opponent, Alexander Hamilton, endorsed him. “Burr is unprincipled,” Hamilton wrote. “He is for or against nothing but as it suits his interest or ambition.” Sound familiar? Some politicians today say exactly the same about their opponents.

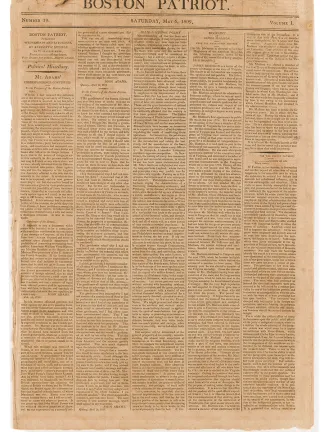

James Madison had been the central player in the writing and ratification of the Constitution, and in three decades of public service he was active in Congress and as Jefferson’s vice president. It seems strange that after those accomplishments, Madison in 1809 needed the introduction to the public that he was given in the Boston Patriot, visible on the next page, following his victory in the 1808 election. But the same phenomenon is true today: the public forgets.

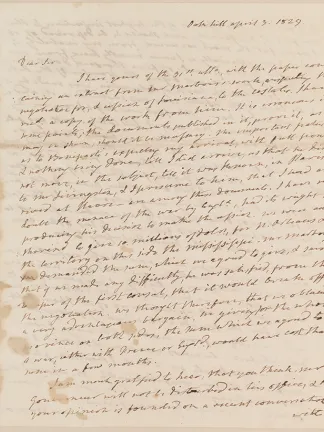

A hero of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, James Monroe in 1816 had served in government for decades, as a senator, governor of Virginia, foreign minister, and secretary of state and of war. His letter of 1829 recalls the Louisiana Purchase, in which he played a key role as its negotiator. Like Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Joe Biden in 2020 in the Democrat Party, Monroe in 1816 felt it was his turn to receive the Republican nomination for president.

The politics of the remaining four Virginia-born presidents are well illustrated in the vast political collection given to the VMHC by Dr. Allen Frey. William Henry Harrison was derided by his political opponents as content to live in a log cabin with a barrel of hard cider; his Whig party welcomed the homespun image and anointed him the “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” candidate. Opponents labeled John Tyler “His Accidency” because as vice president Tyler was elevated to the presidency when President Harrison died in office. Zachary Taylor, whose distinguished forty-year military career propelled him to high command in the Mexican War, used campaign materials that associated him with George Washington. The “Progressive” president Woodrow Wilson brought reform to banking, trade, business practices, farm loans, and taxes—but he is rejected by today’s “Progressives” because he did little to advance the rights of African Americans and was in fact racist.

How will the extreme polarization of 2020 be viewed a decade or two from now? If history again repeats itself, it will be forgiven and forgotten. In 1814, fifteen years after Washington’s death, Jefferson, who had feuded so much with him, wrote in a famous letter in the VMHC collection (to Walter Jones, January 2, 1814) that Washington “was indeed, in every sense of the words, a wise, a good, & a great man.” He admitted, “we were indeed dissatisfied with him on his ratification of the British treaty [the Jay Treaty that disfavored France], but this was short lived,” and “I am convinced he is more deeply seated in the love and gratitude of the [R]epublicans, than in the Pharisaical homage of the Federal monarchists, for he was no monarchist.”