The death of former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton — resulting from his famous 1804 duel with Vice President Aaron Burr — did not end the vitriolic political discourse common in that era. But it did fuel an anti-dueling movement, and in 1810, killing an opponent in a duel became a capital crime in Virginia.

In the late afternoon of April 8, 1826, seven men — an Army general, five members of Congress and the U.S. Secretary of State — intended to break the law.

Crossing the Potomac River from Washington into Virginia, Sen. John Randolph of "Roanoke" — the name of his Charlotte County plantation — carried an oak case that held a matched set of .50-caliber pistols. (Coincidentally, they were made by the same London company that produced the pistols used 22 years earlier by Hamilton and Burr.)

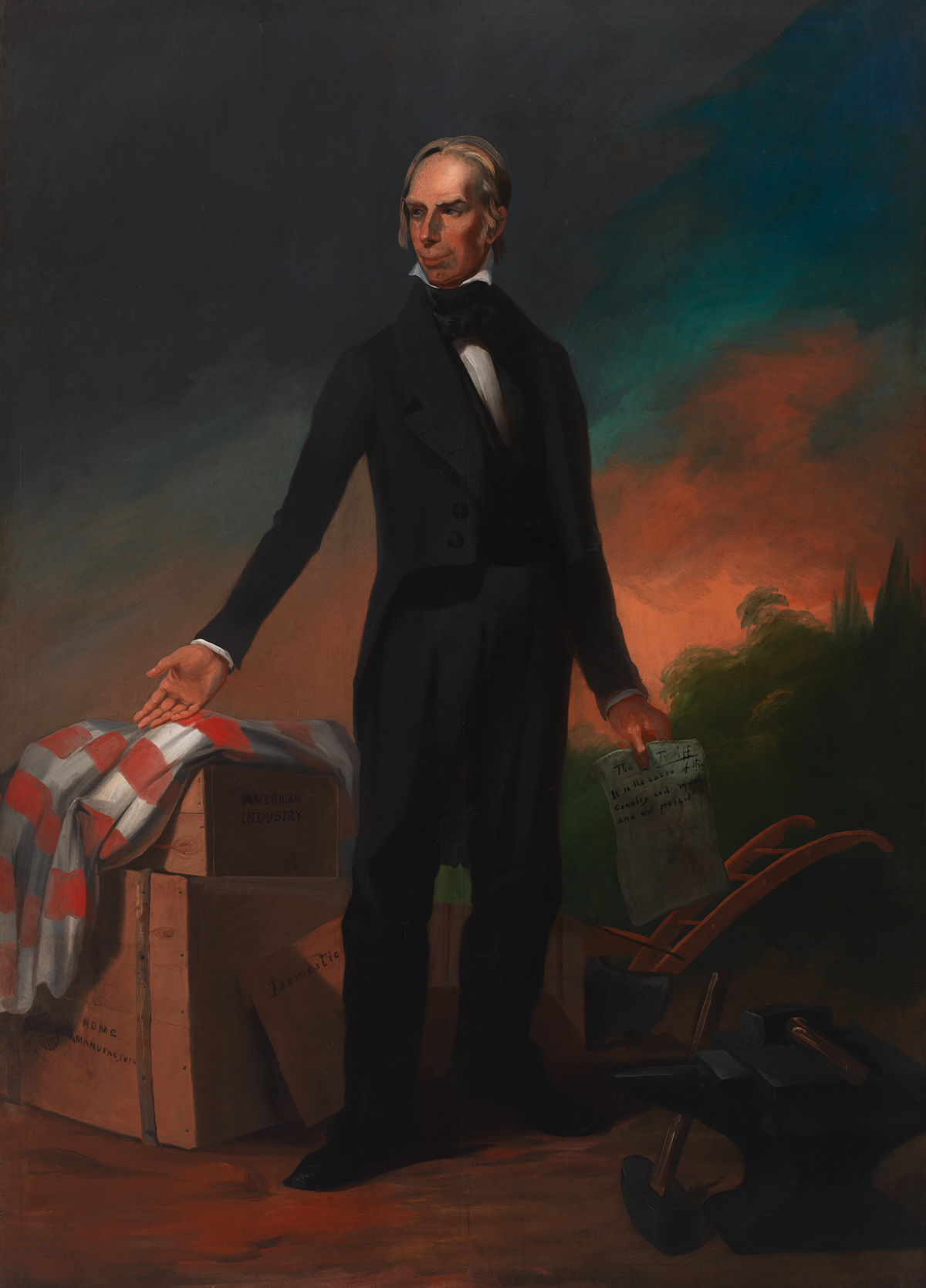

Randolph, who served in Congress (mainly the House) for more than 25 years, was a quick-thinking orator with a remarkable wit and an uncontrolled temper. The eccentric, profane, hard-drinking, opium-addicted Virginian was a staunch states’ rights advocate who consistently fought to restrict the power of the federal government.