Raid, Incarceration, and Execution

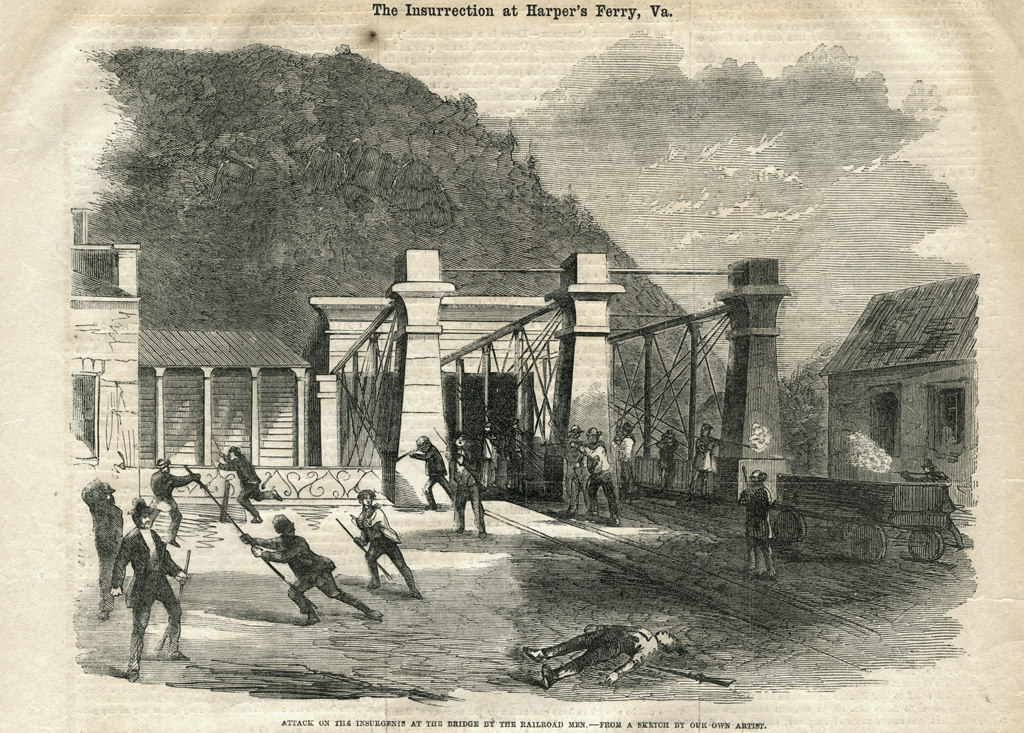

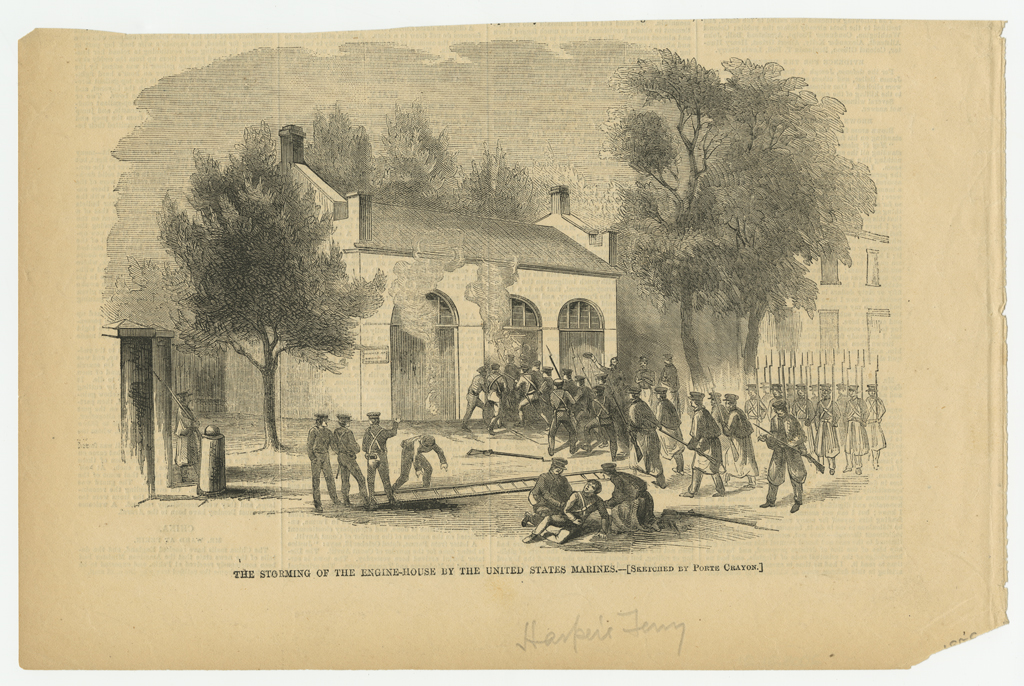

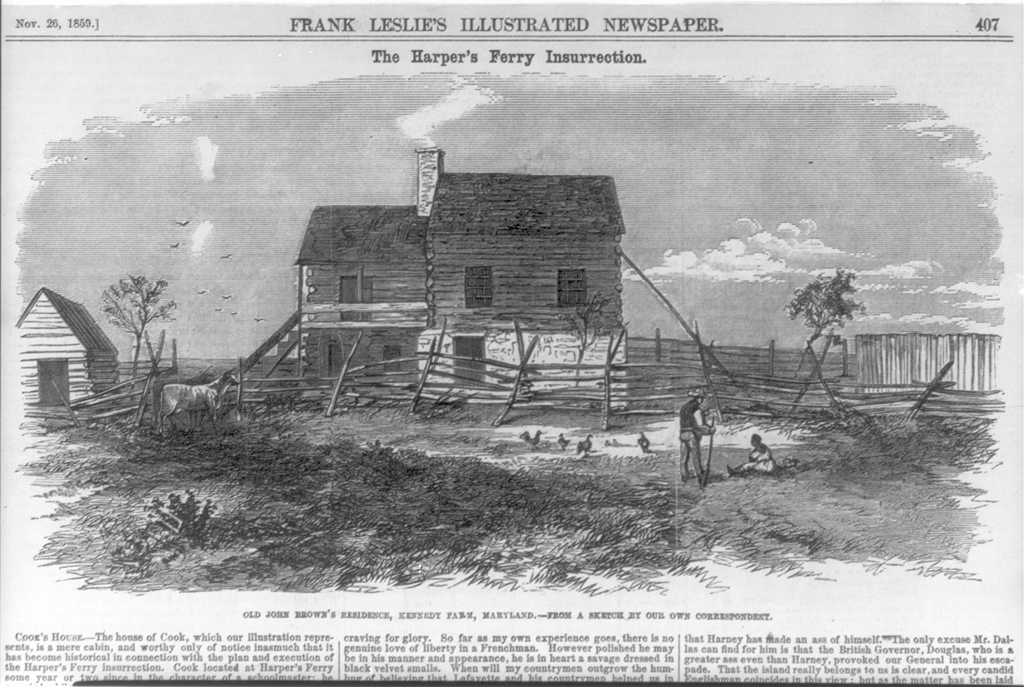

Although John Brown and his followers easily captured the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), no army of runaway slaves and sympathetic whites emerged to join his movement. During a day-and-a-half of skirmishing, townspeople and the local militia killed or wounded many of his men. On October 18, a detachment of U.S. Marines commanded by Robert E. Lee captured the remaining insurgents. Ten days later Brown was placed on trial and charged by the state with treason, murder, and inciting slaves to revolt.

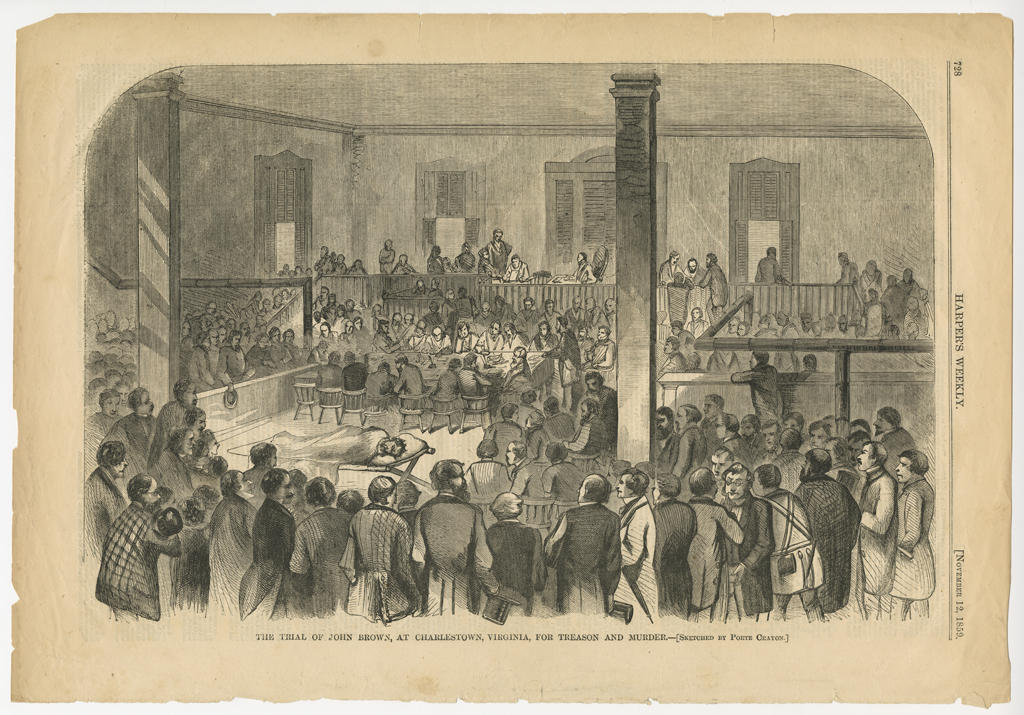

At his trial, Brown argued that his deeds were justified because they were based on Christian principles and his goal was to end slavery. He said that his plan was simply to free a few enslaved people and shed no blood. That statement was entirely different from what he had boasted when he was captured—that his intention was to spark a widespread slave insurrection. A few days after the speech, Brown changed his story—he argued that he had been confused in court and that he had hoped the raid would start a rebellion. The important point is that the courtroom speech—which denies the endorsement of violence—was read throughout the North, in newspapers and in pamphlets. It caused many there to reassess Brown and side with him. The speech, however, had no bearing on the outcome of the trial: Brown was sentenced to hang on December 2.

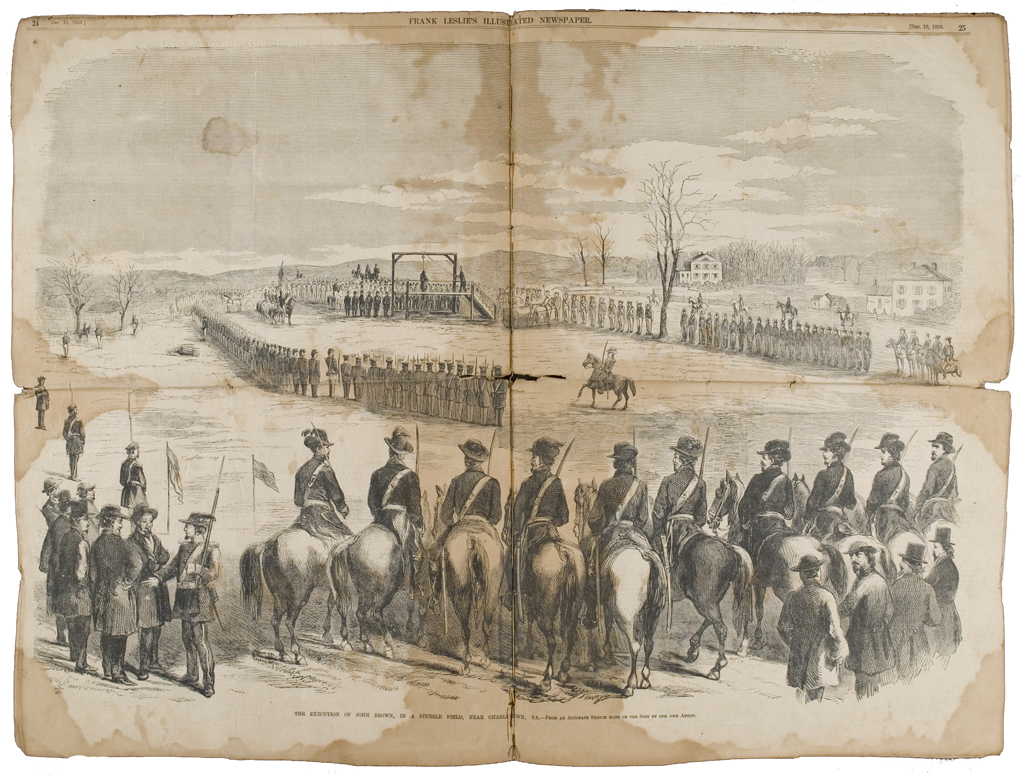

In the following weeks John Brown wrote emotional, persuasive letters from jail that defended the antislavery movement and carefully omitted any mention of the widespread human slaughter that would have accompanied his planned slave revolt. The letters, combined with his courtroom testimony, caused northerners and southerners to reassess their original impressions. Brown could no longer be dismissed as a mere madman who had launched an impossible crusade. When John Brown was hanged, he became a martyr for the abolitionist movement.