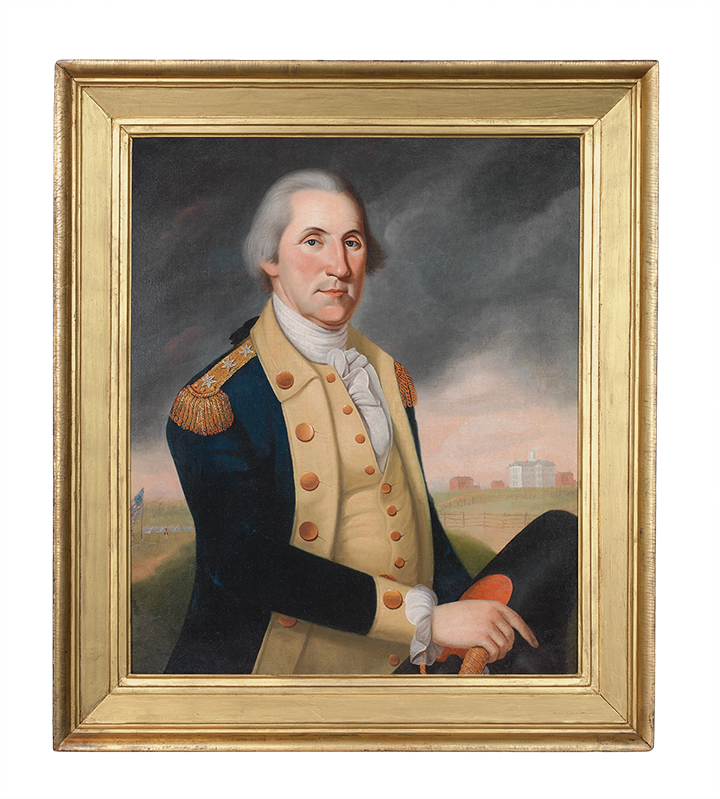

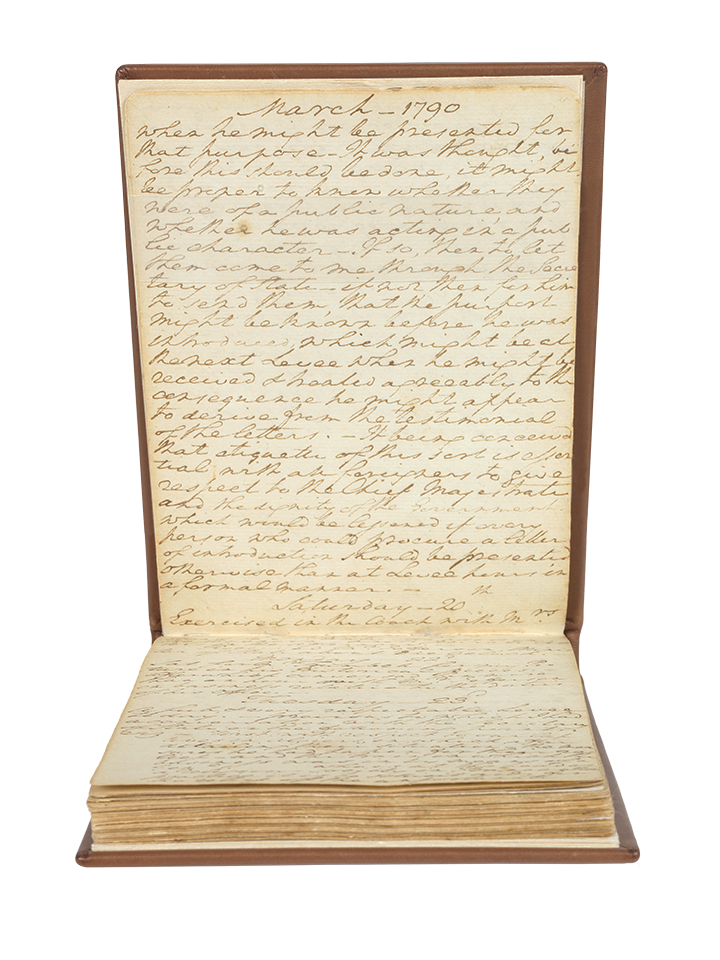

Both the first object acquired by the Virginia Historical Society and arguably one of the best objects in the VMHC collection are tied to a special relationship that existed between John Marshall and George Washington. The first object is a copy of Marshall’s biography of Washington. The other is the diary that President Washington kept in 1790 – 91 during his first term.

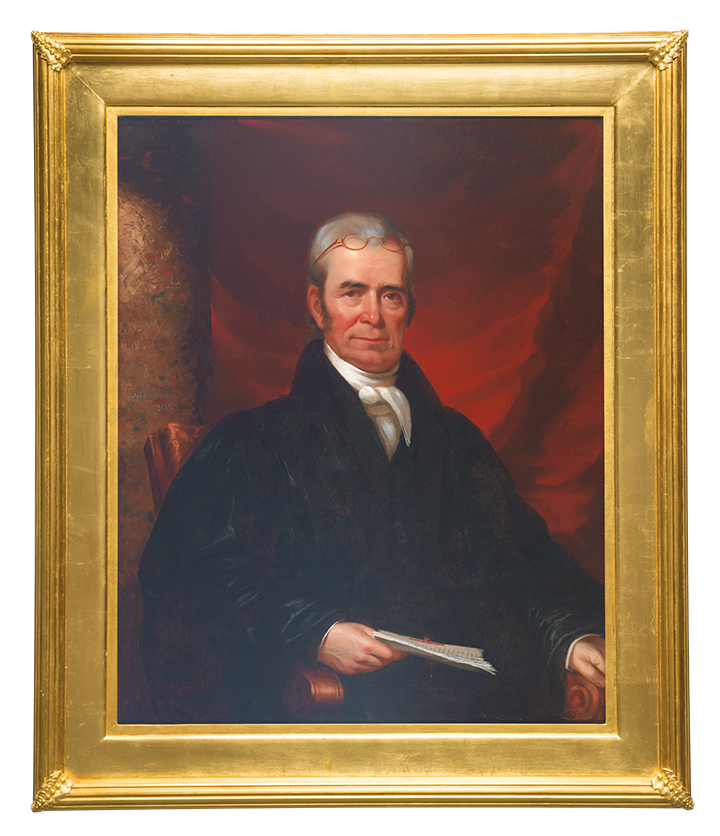

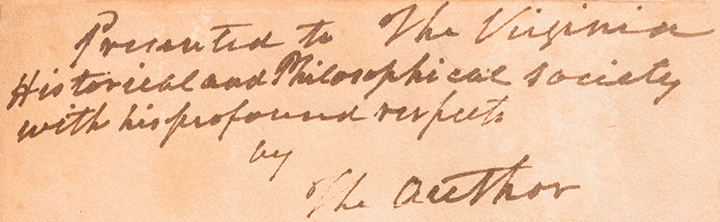

The story of the first object has often been told. In 1831, when concerned Virginians created a “society” to preserve the records of their illustrious predecessors who had helped found the nation, they elected as the institution’s president a Founding Father. In gratitude, John Marshall presented the society a copy of his biography, The Life of George Washington, inscribed by the author “to the Virginia Historical and Philosophical Society.”

The story of how the best object was acquired has largely been forgotten. Institutional records reveal that in 1859 it was given by James K. Marshall. How did he acquire it? James K. Marshall was one of John Marshall’s five sons. Trained as a banker, he served as executor of his father’s complex will. John Marshall had accumulated considerable wealth and property. In settling the estate, James K. Marshall probably came upon Washington’s diary among his father’s possessions. But how did John Marshall come to own it?