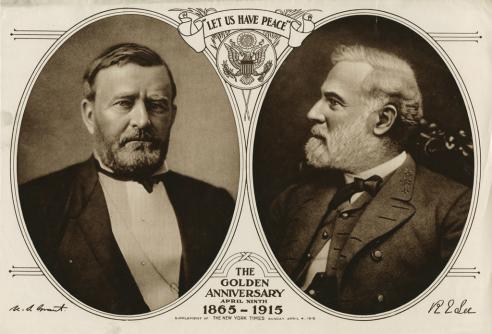

Reconciliation

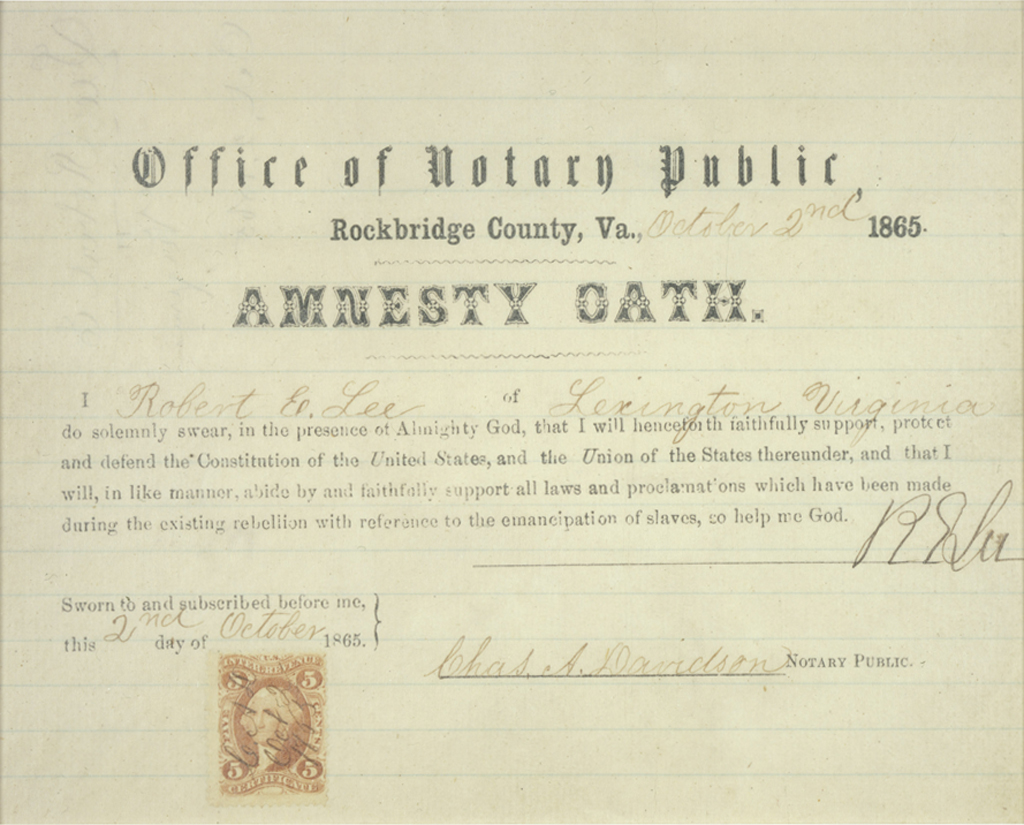

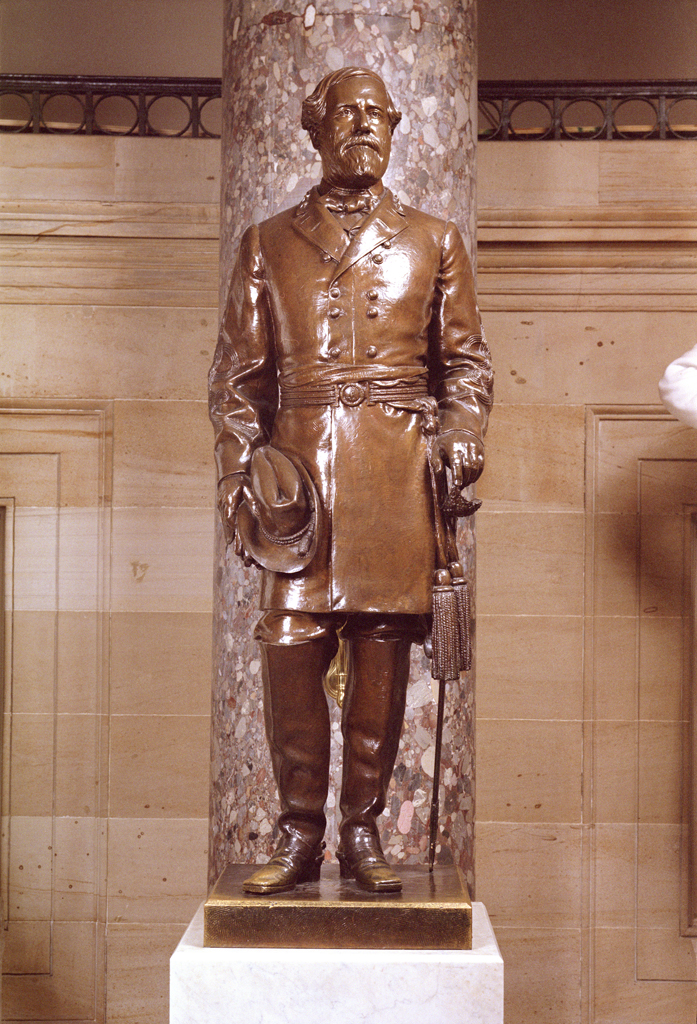

After Appomattox, Ulysses S. Grant was the savior of the United States, while Robert E. Lee was the greatest hero of the Lost Cause. Their roles during the war had been clear. It was now time for each to find ways to be of service during peacetime. Lee decided to work during the postwar period to restore the country. He preached submission to authority, promoted political harmony, and became president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, to prepare the next generation of southern men to become useful citizens.

As general of the army, Grant demanded that former Confederate officers be treated fairly, while at the same time he determined when and where to position peacekeeping troops in the South. As president, he sought to maintain the peace and restore economic prosperity. His goal was to protect all citizens, including the freedpeople and American Indians, and he dealt fairly with foreign nations. Although scandals would later rock his administration, Grant never profited from the machinations of his subordinates.

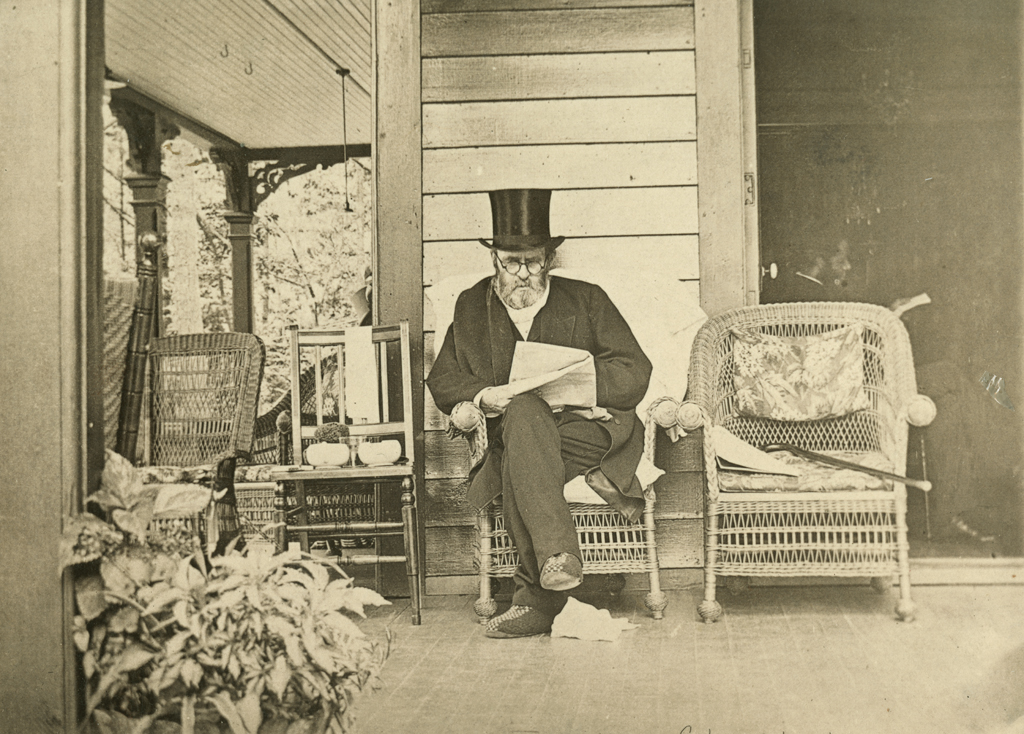

President of Washington College, 1865–70

As had George Washington eighty years before, Robert E. Lee had been saddened by the lack of education he had found among the young soldiers under his command. Beginning in the fall of 1865, when he became president of Washington College, he could attempt to address that shortcoming. In the process, the general dramatically expanded the school's classical curriculum to include emphases on the sciences, commerce, and agriculture. In that way, the students would be provided with the skills to forge a New South. He also inculcated the ideals of duty and honor that had governed his own life.

Lee's greatest postwar legacy, however, was toward national reconciliation. Although he had ostensibly retired from the national spotlight, Lee became a voice of moderation and patient compliance. In his public letters, several of which were reprinted in newspapers, he urged that "all should unite in honest efforts to obliterate the effects of war and to restore the blessings of peace." Lee vowed to do "all in my power to encourage our people to set manfully to work to restore the country, to rebuild their homes and churches, to educate their children, and to remain with their states, their friends and countrymen." Thus when Congress ordered the drafting of new constitutions in the former Confederate states and disgruntled southerners contemplated a boycott of the system, Lee announced that it was "the duty of the [southern] people to accept the situation fully" and that every man should not only "prepare himself to vote" but also "prepare his friends, white and colored, to vote and to vote rightly." Lee's code of conduct demanded submission to authority. With characteristic self-discipline, he put the past behind him and moved forward. Many southerners proved willing to follow Lee's example.

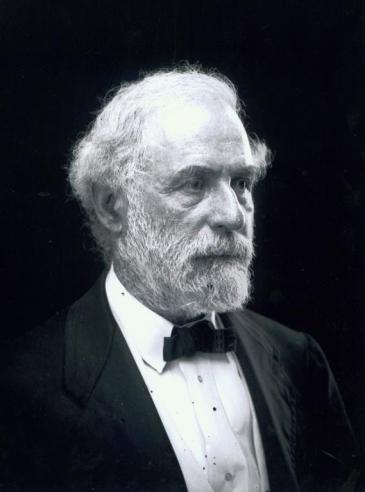

President of the United States, 1868–76

President of the United States, 1868–76

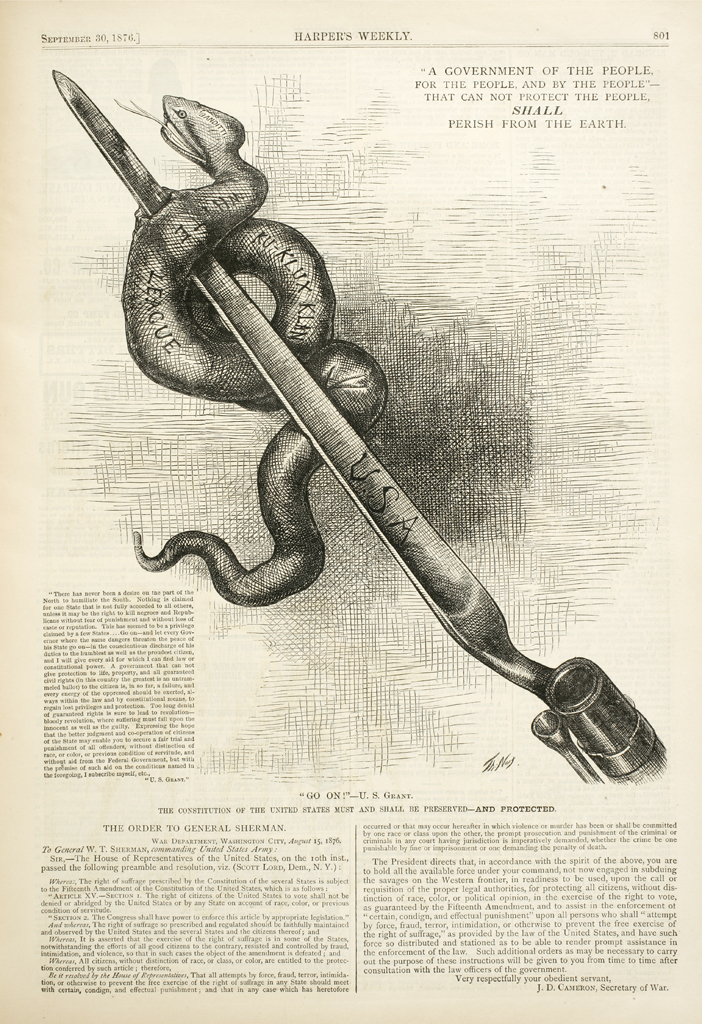

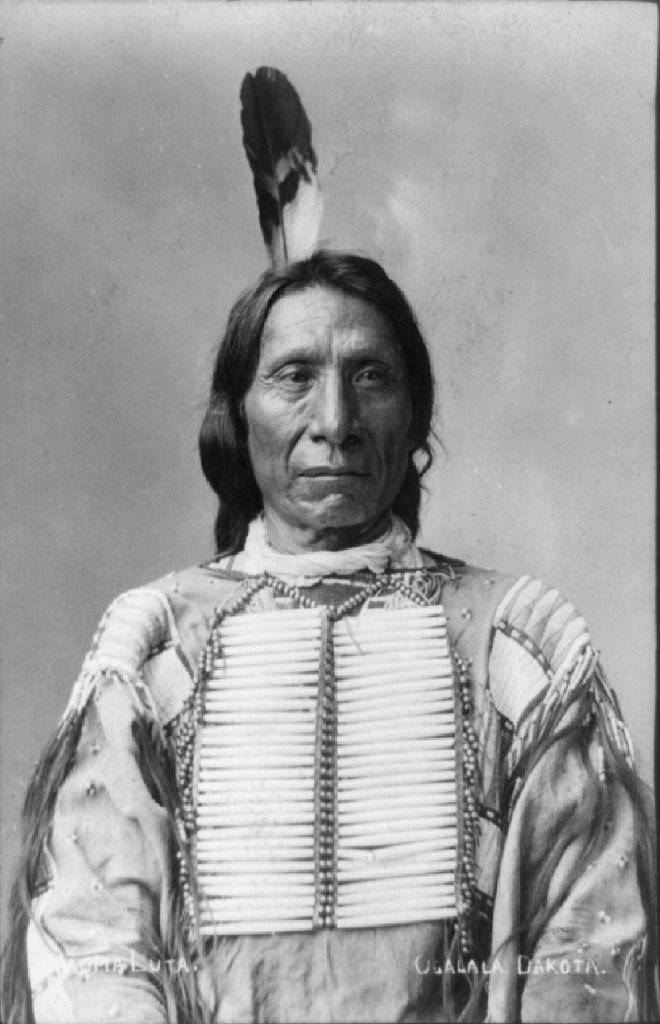

Grant's 1868 campaign slogan, "Let us have peace," defined his motivation and assured his success. As president for two terms, Grant made many advances in human rights. He won passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave the freedman the vote, and the Ku Klux Klan Act, which empowered the president "to arrest and break up disguised night marauders." He pressed for the former slaves to be "possessed of the civil rights which citizenship should carry with it." Grant's attempts to provide justice to American Indians marked a radical reversal of what had long been the government's policy: "Wars of extermination . . . are demoralizing and wicked," he told Congress. The president lobbied, not always successfully, to preserve Indian lands from encroachment by the westward advance of pioneers.

Grant pledged to "deal with nations as equitable law requires individuals to deal with each other." He avoided a war with Spain that seemed certain when Madrid crushed a revolution in Cuba, and he averted a war with Britain over financial claims for Civil War losses caused by English-made vessels and over fishing and boundary disputes with Canada. He sought, without success, to acquire the island of Santo Domingo as a potential refuge for "the entire colored population of the United States, should it choose to emigrate."

Grant's administrations were characterized in part by corruption brought on by appointees to whom the president gave too much power and to whom he remained steadfastly loyal. Of the half-dozen scandals that troubled contemporaries and have alarmed historians, several involved the bribery of administration officials. There was never any evidence that Grant himself had any part in, or profited from, these schemes.

Conclusion

Had Robert E. Lee taken command of United States forces in spring 1861, the war would probably have come to an end more quickly and slavery would most likely have survived it. Lee would have been the hero of the nation, and he could easily have become the eighth president from Virginia. This was in his grasp, but he let it go to preserve his personal honor and to defend his home and his family. Those who argue that he chose to fight for slavery rather than against it, and that this is all one needs to know about Lee, lose sight of the extent of the sacrifice that he made. His decision was not about defending slavery; it was about doing what he thought was right.

As general and president, when Ulysses S. Grant brought his marvelous talents of observation and dedication to any job, he rarely failed. The country had to be preserved. He made sure that it was. After the war, laws had to be enforced. He carried out his orders. And as president he tried his best to insure that the U.S. victory brought about a democracy that included all of the people, a society that would not be based on race, wealth, or descent.

As general and president, when Ulysses S. Grant brought his marvelous talents of observation and dedication to any job, he rarely failed. The country had to be preserved. He made sure that it was. After the war, laws had to be enforced. He carried out his orders. And as president he tried his best to insure that the U.S. victory brought about a democracy that included all of the people, a society that would not be based on race, wealth, or descent.

The accomplishments and shortcomings of both Lee and Grant were tied to the values of the regions that bred them. They lived through eight decades of incredible change. By 1870, the nation was no longer the united states of the antebellum years. Black people were free. The power of the central government was confirmed and strengthened. New lands had been opened for settlement, and a transcontinental telegraph and railroad had come into service. It was a larger yet in some ways a smaller country that was united in a way that it had never been before. These United States had now become The United States.