1825 to 1860

Political Decline and Westward Migration

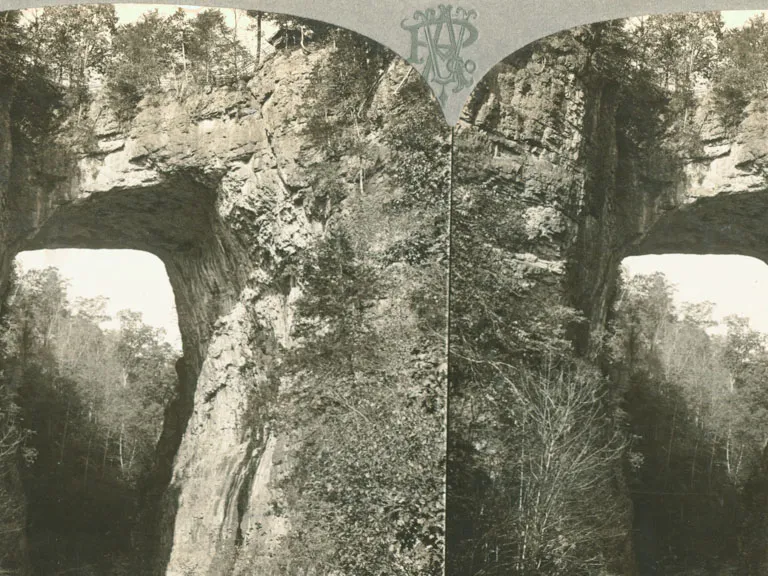

The political stature of Virginia declined on the national stage when no successors of ability emerged to replace the Founding Fathers. At the same time, exhausted soil brought agricultural failures. By 1800, tobacco production had depleted the soil of eastern Virginia. Landscape east of the Blue Ridge Mountains had been transformed into wasted fields and what one agriculturist called the “eyesores” of ruined farms. Artists and writers saw a melancholy beauty in the ruins and worn land. Farmers, however, saw instead good reason to pack up and head west. At the same time, farmers in the Shenandoah Valley and Piedmont produced an abundance of corn and wheat, enabling Virginia to remain the leading agricultural state in the South. Evidence of the agricultural rebirth there was seen in the prosperity of market towns, where local produce was sold and where planters purchased goods.

Political Decline

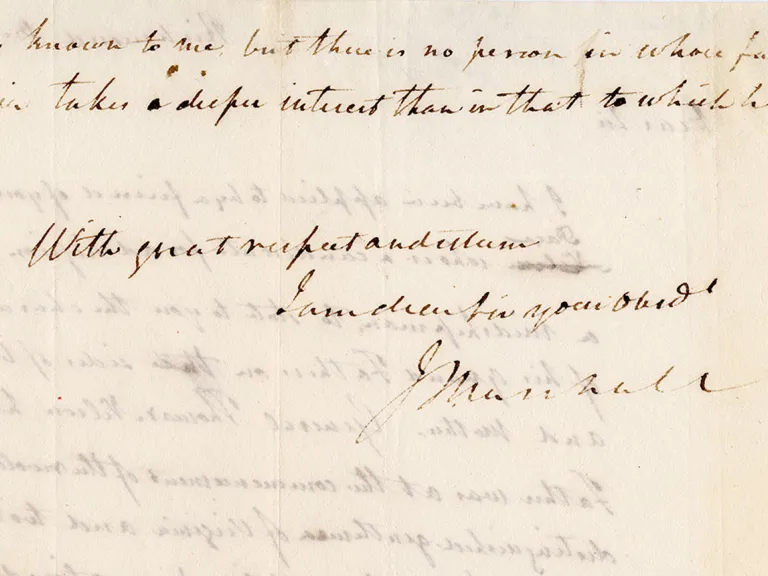

The presidencies of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe were over. In the rising generation of Virginians, only John Randolph possessed exceptional talent, but he was feared, not admired. The state had lost power in Congress because of population shifts. ” What has become of our political rank and eminence in the Union?” worried Benjamin Watkins Leigh. “Virginia has declined and is declining.”

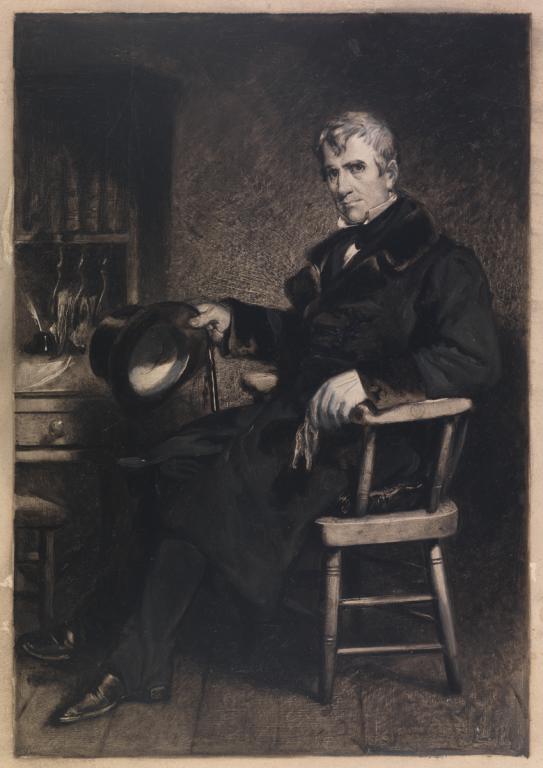

William Henry Harrison (1773–1841), Ninth President of the United States, 4 March–4 April 1841

Born in Charles City County, Harrison served in the army in the old Northwest Territory (north of the Ohio River) and was appointed governor of the Indiana Territory. He negotiated treaties with multiple tribes of Indians in which they conveyed title to fifty million acres of land. Harrison defeated the Shawnee chief Tecumseh in 1811 at the battle of Tippecanoe and recaptured Detroit from the British during the War of 1812, winning military fame that eventually earned him the presidency.

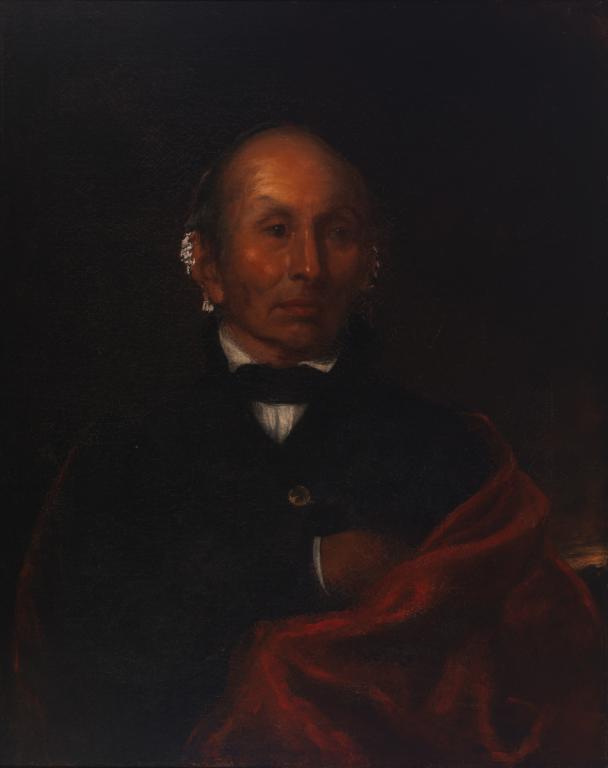

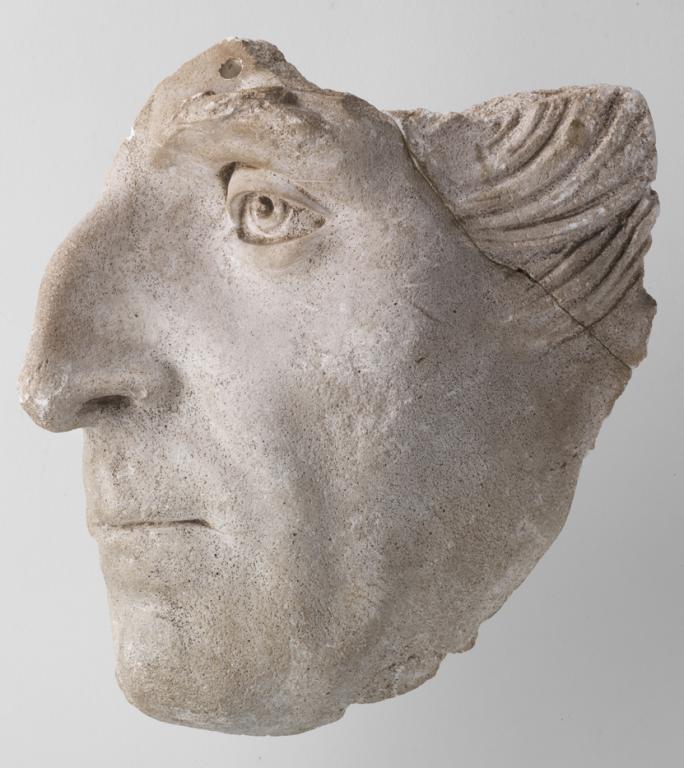

Black Hawk (Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak), Sauk War Chief Who Confronted Harrison

Black Hawk disputed William Henry Harrison’s treaty of 1804 whereby the Sauk and Fox nations ceded to the United States their lands in present-day Illinois. In an effort to regain that lost territory, Black Hawk joined British-supported forces during the War of 1812. In 1828, the Sauk and Fox tribes were removed west of the Mississippi River. From Iowa, Black Hawk led incursions back into the Illinois region. In 1832 one incursion grew into a revolt, the unsuccessful “Black Hawk War.”

Defeated, Black Hawk was one of several Indians carried east. He met President Andrew Jackson, became something of a curiosity, and was briefly incarcerated in Virginia at Fort Monroe.

John Tyler (1790–1862) of Charles City County, Tenth President of the United States and the last Virginia-born President to Remain in the Commonwealth.

John Tyler endorsed states’ rights, limited federal government, and the virtue of agrarian life. He first served as a Virginia legislator and governor, a U.S. representative and senator, and as vice president. As president, Tyler provoked a war with Mexico and thereby acquired Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. In 1861, he opposed secession but then served in the Confederate government.

Zachary Taylor (1784–1850), Twelfth President of the United States, 1849–1850

Born in Orange County, Virginia, Taylor was the son of a Revolutionary War officer who was granted land in present-day Kentucky, where the family moved. “Old Rough and Ready’s” forty-year military career propelled him both to high command in the Mexican War, where he was praised as the American “David” sent against the Mexican “Goliath,” and to the presidency. Taylor was a southerner and slaveholder who opposed the expansion of slavery. He died only sixteen months into his presidency, possibly from gastroenteritis (viral infection).

Agricultural Decline and Westward Migration

In 1830, John Randolph complained that Virginia’s landscape was “worn out.” Overproduction of tobacco had exhausted the soil of eastern and central Virginia. Some blamed farmers for failing to rotate crops, rest fields, and fertilize. Others faulted the absence of a system to transport and market crops. To many, the slave force was unproductive, and import tariffs benefited the northern factory owner at the expense of southern farmers.

Pioneers eventually pushed to the farthest reaches of “the West.” Initially, emigrants were lured to Tennessee along Valley of Virginia roads. Kentucky and Illinois––first as Virginia counties and later as states––also beckoned, along with Indiana and Missouri. Ohio attracted the most Virginians. Thousands of slaves were taken to Mississippi and Alabama. Virginians later emigrated to Texas and California.

Included in the westward migration were hundreds of thousands of enslaved African-Virginians. The magnitude of their passage affected the settlement of the continent. In the exhausted tobacco fields of eastern Virginia, slave labor was unprofitable. But slavery brought prosperity in the Deep South, where cotton, which replaced wool as the staple for clothes, could be grown successfully with slave labor.

The agricultural decline of the Tidewater bypassed the Shenandoah Valley––a landscape of mostly flat, fertile terrain with few rivers. Its slave population never was large. The region was populated by Virginians of English descent moving westward, joined by Germans and Scots-Irish migrating from Pennsylvania. As Thomas Jefferson had advocated, they established smaller-sized farms in clusters around small market towns, not large urban centers.

The German and Scots-Irish presence in the Shenandoah Valley

The German presence in the Shenandoah Valley was visible because many there spoke and wrote only German. A printing industry emerged to reach those settlers. The Germans proved to be particularly industrious and self-sufficient, proficient not only as farmers but also in making utilitarian ironwork and pottery marked by its artistry. They had little need of or interest in slavery. Most were members of the Lutheran Church.

Initially from Scotland, northern England, and Ireland, the Scots-Irish migrated down the Shenandoah Valley from Pennsylvania. They leapfrogged over the earlier German settlements, settling particularly in the mid to southern counties. The Scots-Irish eventually outnumbered all others in Virginia’s western counties, and their culture became dominant amid the mix of peoples there. Most were Presbyterians.