1825 to 1860

Slavery

The 550,000 enslaved Black people living in Virginia constituted one third of the state’s population in 1860. Travelers to Virginia were appalled by the system of slavery they saw practiced there. In 1842, the English novelist Charles Dickens wrote of the “gloom and dejection” and “ruin and decay” that he attributed to “this horrible institution.”

A majority of inhabitants in some of Virginia’s eastern counties were held in bondage. In the western counties, rugged terrain made slavery impractical. In 1829, white citizens there demanded representation in a government controlled by easterners with different interests. In 1861, they formed the new state of West Virginia rather than join the Confederacy.

Slave Life

The majority of enslaved men, women, and children provided agricultural labor for their enslavers. Trained craftspeople worked in skilled trades such as coopering, blacksmithing, and carpentry. A smaller group of men and women cooked, cleaned, served meals, and raised the children of the enslaver’s family. On Sundays, enslaved individuals tended to their own gardens and livestock provided by their enslavers, practiced religion, and engaged with family and friends.

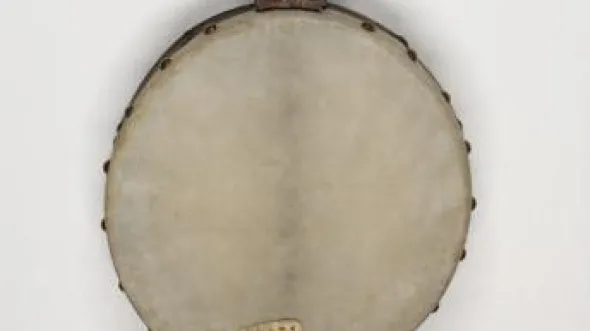

Through their families, religion, folklore, and music, as well as more direct forms of resistance, African Americans resisted the debilitating effects of slavery and created a vital culture supportive of human dignity. At the same time, enslaved Black people exerted a profound influence on all aspects of American culture. Language, music, cuisine, and architecture in the United States are all heavily influenced by African traditions and are part of a uniquely American culture.

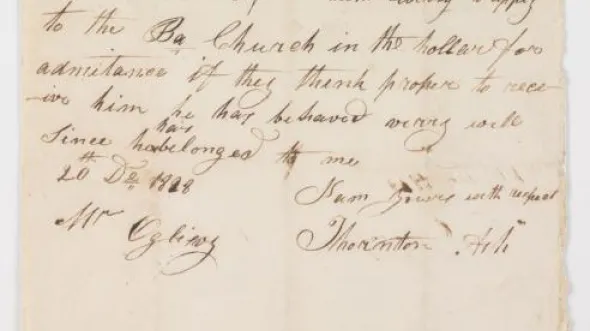

Slave Religion and Folklore

Throughout slavery and beyond, spirituality and the church served a vital role in Black communities. Religious practices nurtured the soul and fostered pride and identity in the face of the dehumanizing effects of slavery and segregation. Baptist and Methodist ministers preached hope and redemption to enslaved people who fashioned Christian gospels into a communal music of spirituals about salvation, deliverance, and resistance. They also helped preserve African traditions through music, funeral customs, and call-and-response forms of worship. Religious meetings—whether secret gatherings in the woods or church congregations—became crucibles for collective activism.

Enslaved African Americans continued a rich tradition of African parables, proverbs, and legends. Through folklore, they maintained a sense of identity and taught valuable lessons to their children. The central figures were cunning tricksters, often represented as tortoises, spiders, or rabbits, who defeated more powerful enemies through wit and guile, not power and authority.

Music and Food

The musical traditions of enslaved communities merged European practices with intricate rhythm patterns, off-key notes, foot patting, and a strong rhythmic drive. Music was incorporated into religious ceremonies as shouts and “sorrow songs;” “field hollers” and work songs helped coordinate group tasks; and satirical songs were a form of resistance that commented on the injustices of the slave system.

African Americans adapted Indigenous, European, and African food traditions—such as deep-fat frying, gumbo, and fricassee—to feed their own families as well as those of their enslavers. Pork and corn were the primary rations issued to those who were enslaved, but they were supplemented by plants and animals grown or raised or gathered from nearby rivers and fields.

The Slave Trade and Slave Auction

After an 1808 act of Congress abolished the international slave trade, a domestic trade flourished. Richmond became the largest slave-trading center in the Upper South, and the slave trade was Virginia’s largest industry. It accounted for the sale—and resulting destruction of families and social networks—of as many as two million Black people from Richmond to the Deep South, where the cotton industry provided a market for enslaved labor.

Prices of enslaved people varied widely over time. They rose to a high of about $1,250 during the cotton boom of the late 1830s, fell to below half that level in the 1840s, and rose to about $1,450 in the late 1850s. Males were valued 10 to 20 percent more than females; at age ten, children's prices were about half that of a prime male field hand.

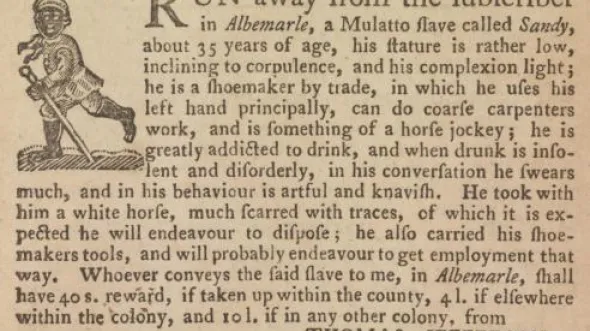

Resistance

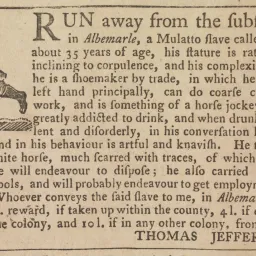

The management of an enslaved workforce was a frequent topic of debate among slaveholders. Over time an elaborate system of controls was developed that included the legal system, religion, incentives, physical punishment, and intimidation to keep enslaved people working. None was completely successful.

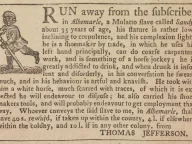

While slaveholders asserted that their workforce was loyal, they also lived in constant fear of a revolt. White southerners prohibited enslaved African Americans from learning to read, restricted their movement, prevented them from meeting in groups, and publicly punished those who attempted to escape slavery. Slave codes also punished white Virginians who assisted Black people in violating the codes.

Denied their unalienable rights of liberty and the pursuit of happiness, enslaved Americans were trapped in a cruel and unacceptable lifestyle. Some enslaved Virginians instigated organized, armed rebellion or attempted escape, even though success was unlikely and punishments included execution and disfigurement. Most engaged in day-to-day resistance—breaking equipment, stealing foodstuffs, slowing the work-pace. The most effective resistance was the formation of a distinct culture that perpetuated African American traditions of music, storytelling, and cuisine, and was bolstered by strong religious beliefs.

Travelers to Virginia were appalled by the system of slavery they saw practiced there. In 1842, the English novelist Charles Dickens wrote of the “gloom and dejection” and “ruin and decay” that he attributed to “this horrible institution.” Inevitably, the intolerable abuses caused a number to commit suicide. A few initiated rebellion––the ultimate crisis imagined by the slaveowner.

Gabriel’s Conspiracy, 1800

Gabriel was a literate enslaved blacksmith hired out to work in Richmond by his enslaver, Thomas Prosser of Henrico County. With some freedom of movement, access to others enslaved men, and information about uprisings elsewhere, Gabriel planned a rebellion against slavery in central Virginia. Two enslaved men betrayed the plot. In response, white Virginians arrested and prosecuted more than seventy men for insurrection and conspiracy. Gabriel and twenty-five of his followers were hanged.

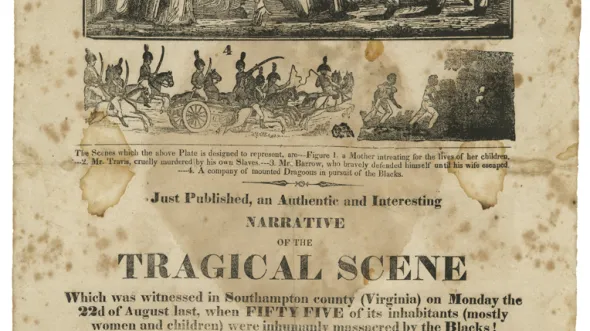

The Nat Turner Revolt, 1831

Nat Turner, an enslaved preacher and self-proclaimed prophet, led the bloodiest slave revolt in U.S. history in Southampton County. Over the course of two days in late August 1831, he and his conspirators killed 58 white men, women, and children before government troops quelled the insurrection. The state tried and executed Turner and 19 conspirators. White vigilantes retaliated with violence, resulting in about 40 additional deaths.

The event sent shockwaves throughout the nation and deepened the divide over slavery. Defenders of the institution blamed “Yankee” influence and what they believed was the violent character of Black people. Antislavery factions argued that this revolt demonstrated the corruptive effects of slavery and refuted enslavers’ claims of the “contented” slave.

Turner’s revolt also prompted Virginia’s General Assembly to debate the fate of slavery in its 1831–1832 session. Legislators considered proposals for abolition, but ultimately decided to maintain slavery. They also passed new restrictions on Black Virginians, including requiring Black congregations to be supervised by a white minister, and making it illegal to teach Black people to read. This was the last time a government of a slave state considered ending slavery until the Civil War.

John Brown’s Raid, 1859

Led by the radical abolitionist, John Brown, eighteen whites and five African Americans, seized the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) in October 1859. Among them was Dangerfield Newby, a former slave from the Shenandoah Valley. For Newby the cause was deeply personal: his wife and children were still in bondage. After a failed attempt to buy their freedom and fearing their sale to the Deep South, Newby joined Brown’s small army. He was killed on the first day of fighting. Brown’s attempt to take rifles stored there, escape into the mountains, and start a slave revolt failed. Five raiders escaped, ten were killed, and nine—including Brown—were captured and executed. Sectionalist tension heightened as southerners feared additional violence.

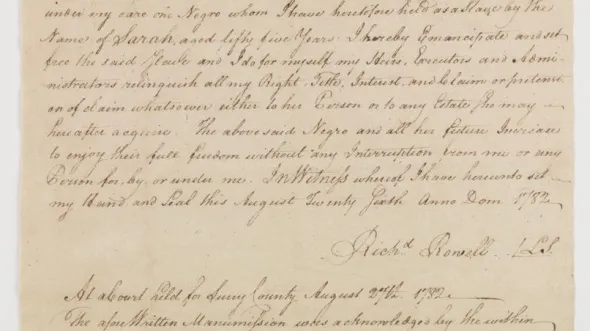

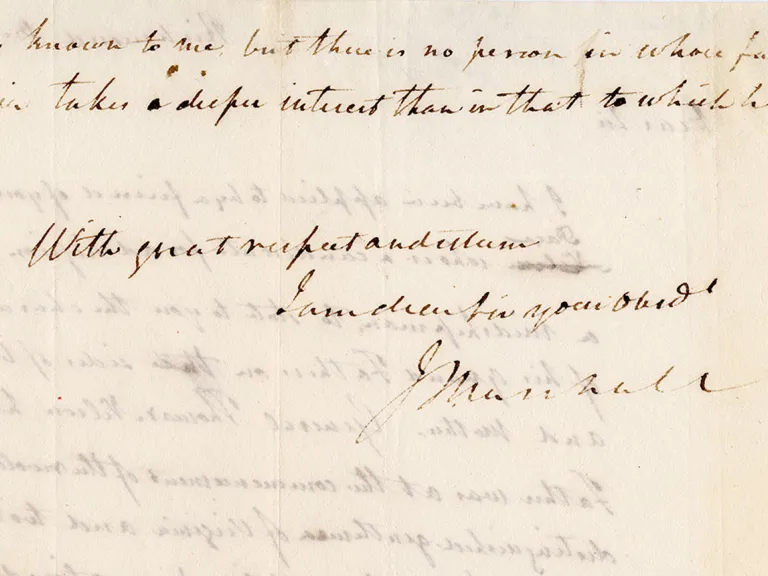

The Abolitionist Movement and Manumission in Virginia

A society for promoting abolition was organized by 1790, and publications appeared as early as St. George Tucker’s Dissertation of 1796. The self-criticism and efforts for abolition ended, however, after Nat Turner’s rebellion of 1831. From that point forward, most white Virginians approved of the practice, denied its evils, and defended it as a “positive good.”

In 1782, the General Assembly allowed enslavers to free the people they enslaved. Some did. Many of their manumission documents are written with condemnation of “the injustice and criminality” of slavery: “Being fully persuaded that freedom is the Natural Right of all Mankind and that it is my duty to do unto others as I would desire to be done by in the like situation, I hereby Emancipate and set free the said Slave ______.”

The Colonization Movement

The growing number of free Black individuals in Virginia—more than 30,000 in 1810—challenged the assumption that black skin equaled enslavement. Free persons of color also presented what enslavers feared was a dangerous example. These tensions prompted the 1816 creation of the American Colonization Society, devoted to removing free Black Americans to Africa. A number of white Virginians—including James Monroe and John Randolph of Roanoke—joined antislavery northerners in this effort.

The colonization movement was controversial among Black Americans. As New York City’s Colored American newspaper explained, “This Country is Our Only Home. It is our duty and privilege to claim an equal place among the American people.” In 1830, Liberia had only about 1,400 settlers. Ultimately, 15,000 Black people emigrated and—in some ways—patterned their society after the American South.