1764 to 1824

The Revolutionary Era in Virginia

Virginia—the largest and most populous colony—played a major role in winning independence and determining the values and aspirations of the new nation. At both the start and end of the Revolutionary War, Virginia became a battlefield. In 1775, Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor, was repulsed at the battle of Great Bridge and he retreated to Norfolk. In 1781, British forces were engaged at the supply center of Petersburg, and Lord Cornwallis surrendered his army at Yorktown. Virginia’s political leaders tackled the critical issue of what rights the new American government should guarantee its citizens.

The Voice, the Pen, and the Sword of the Revolution

Patrick Henry was the “voice” of the Revolution. His incendiary speeches turned public opinion in support of American independence from Great Britain. Thomas Jefferson was the “pen.” His eloquent writings provided justification for Americans independence from Great Britain. George Washington was the “sword.” His masterful command of volunteer forces brought victory over the most powerful army in the world.

“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death”

Beginning in 1763, Patrick Henry delivered daring speeches that attacked the power of the English monarchy and government and advanced colonial rights. His powerful style of speaking was shaped by the evangelical preacher Samuel Davies, to whom he listened as a youth. George Mason explained, “Every word he says commands attention, and your passions are no longer your own when he addresses them.”

“All Men Are Created Equal”

“Whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of human rights, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.” Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence justified the American decision to establish a “new government.” “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” It also proclaimed that a pure and near-perfect world is in fact attainable. This vision of equality and justice has become the American dream.

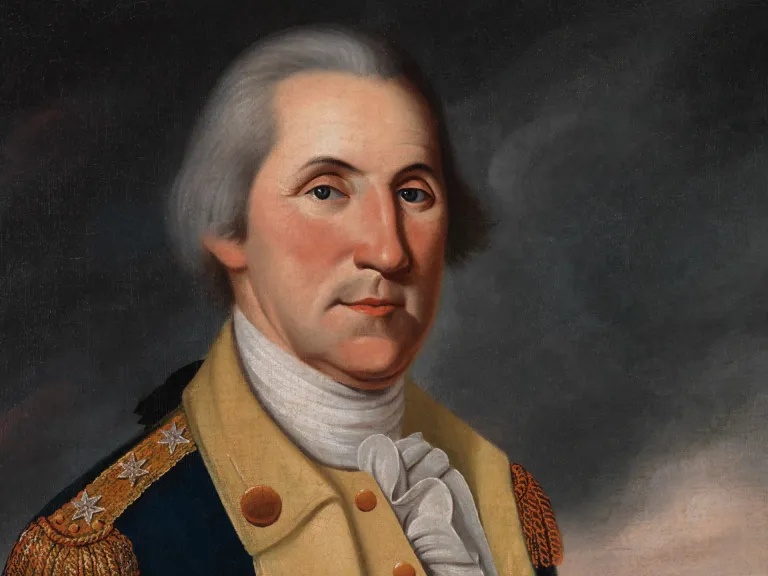

Commander of the Continental Army

Washington not only commanded the Continental Army, he also shaped it and created its identity. His personal standards became a model and an inspiration for those who served under him. “His mind was great and powerful; no judgment was ever sounder,” wrote Thomas Jefferson. “He was incapable of fear, meeting personal dangers with the calmest unconcern. His deportment was easy, erect, and noble; the best horseman of his age.” “He was, indeed, in every sense of the words, a wise, a good, and a great man.”

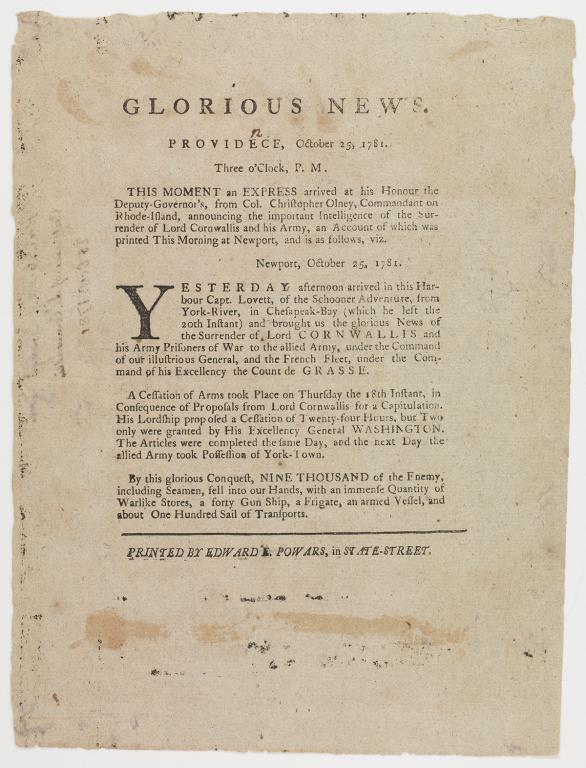

The Victory at Yorktown, 1781

British forces had captured Charleston and pushed into the Carolinas and Virginia. Lord Cornwallis, with an army of 7,000, established a base of operations at the port of Yorktown. Washington, encamped outside New York City, sent a force under the marquis de Lafayette to confront him. When a large French navy arrived to assist, all moved to entrap Cornwallis’s army. With his surrender, the British lost their resolve to continue the war.

Creating an American Government

While the Revolutionary War raged on the battlefield, Virginia’s political leaders worked to conceive a government better than the one that they rejected. George Mason, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson looked to philosophers, such as the Englishman John Locke, for ideas about how nations should be governed. They concluded that people (by which they meant white males) have inherent human rights, primarily life and liberty, and the purpose of government is to serve those people by protecting those rights. Within government, power must be separated. Church and state must be separate.

The Guarantee of Human Rights

America was conceived to protect human rights. Many of the fundamental ideas that underlie this enlightened democracy were developed by Virginians. The concept that all men are created equal with unalienable rights was stated by George Mason in the Virginia Declaration of Rights (June 1776) and then by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence (July 1776). The idea that the role of government is to serve the people was stated by Mason in the Virginia Declaration and by Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence. The idea to separate the powers of government was introduced by Mason in the Virginia Declaration and repeated by James Madison in the U.S. Constitution (1787). The idea that citizens must be given the right to vote was stated by Mason in the Virginia Declaration and by Madison in the Constitution. The idea that citizens have the right to a fair trial and due process of the law was stated by Mason in the Virginia Declaration and by Madison in his amendments to the Constitution (1791). The idea that citizens must be allowed freedom of speech and of the press was stated by Mason in the Virginia Declaration and by Madison in his amendments to the Constitution. The idea that citizens must be allowed freedom of religion was stated by Mason in the Virginia Declaration, by Thomas Jefferson in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786), and by Madison in his amendments to the Constitution. The idea that standing armies are a threat to liberty was stated by Mason in the Virginia Declaration and by Madison in his amendments to the Constitution.

The Struggle for Religious Freedom

The Church of England (the Anglican Church) was the state-mandated religion in Virginia; it was funded by public taxes. Only its clergy could baptize and consecrate marriages. Baptists and other dissenters were abused. James Madison and Thomas Jefferson saw religious freedom as a natural right. Jefferson’s law that separated church and state was passed in 1786 with the help of George Mason and Madison, and the Anglican Church became the Episcopal Church of Virginia.