1861 to 1876

War on the Home Front

For some, the war brought deprivation, horror, and loss right to their very doorsteps. For others, the war brought an uncertain journey into freedom from slavery. In the countryside, armies destroyed roads and bridges, seized food and livestock, and turned houses into hospitals. In Confederate-controlled cities, overcrowding, shortages, inflation, and hunger plagued everyone. In Northern Virginia, the Eastern Shore, and Norfolk the liberties of residents were restricted by occupying Union forces. The western counties suffered pitiless guerrilla warfare. Virginia possessed the largest number of the estimated 200,000 southerners—slaves, Unionists, and Confederates—who fled their homes during the Civil War.

The Secession of Virginia, 1861

After seven Deep South states seceded and Confederate troops in Charleston fired on federal Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to put down the rebellion. Officials in Richmond faced a decision: send militia units to fight fellow southerners or join the southern states in secession. Their choice to secede determined the magnitude, military strategy, and duration of the Civil War.

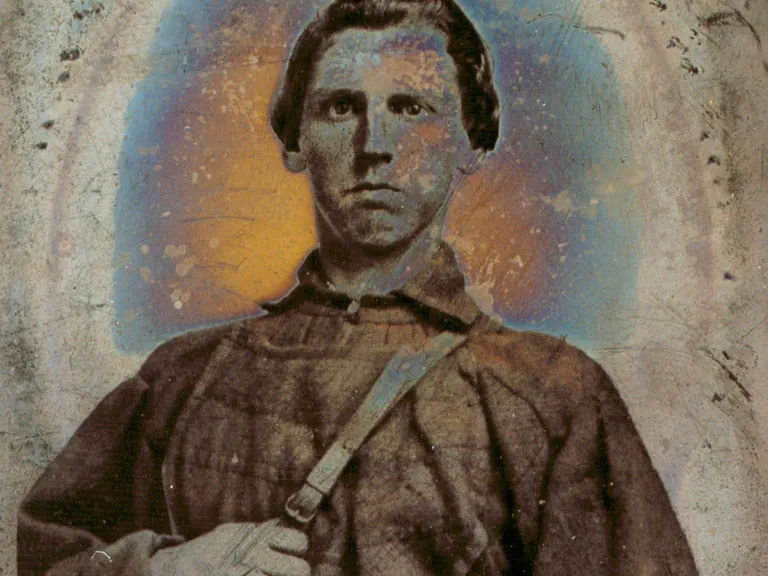

In 1861, thousands of white men rushed to answer the call to arms––to preserve the Union or to repel northern invaders. Two years later, cash incentives and the draft were required to refill the ranks, and the Union army opened enlistment to African Americans hoping to strike a blow against slavery. Ultimately, 3,000,000 men fought to decide the future of the United States.

Making Do, and Doing Without

The needs of the Confederate armies and a Union naval blockade led to shortages of food, fuel, and clothing. Many white women were forced to learn household skills—such as spinning, weaving, and braiding straw—either to outfit themselves or to sell or barter for food and other items. Black women also suffered wartime deprivations, but the institution of slavery taught them to make do with scarcity.

The removal of men into the army demanded increased participation of women—both black and white—in ways previously discouraged. They took over the management of shops and farms. Slaveholding women faced the additional challenge of managing and providing for slaves. Black and white mothers struggled to provide shelter, nourishment, and safety for their families.

Virginia’s children experienced uncertainty, hardship, and violence that forced them to mature quickly. Most helped support their families by taking jobs that fathers and brothers left vacant. Many worked outside the home in wartime industries. Children of “contraband” slaves gathered in unhealthy, overcrowded camps in Northern Virginia or the Tidewater where they worked to earn money to eat.

Slavery During the War

Although thousands escaped, most enslaved Virginians continued working on farms, in factories, and serving households throughout the war. They took advantage of the war’s upheaval to gain some measure of autonomy for their families. The wartime actions of most black Virginians exhibited their strong desire for freedom, and nearly all who chose not to escape welcomed the Union army as liberators.

The fugitive slave law called for the return of fugitives to their masters, but the onset of war and the exodus of many slaves caused federal officials to reconsider. In May 1861, the Union commander at Fort Monroe decided to accept runaways as contraband of war—property useful to the enemy—because otherwise the slaves’ labor would aid the Confederacy.

On September 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln declared all slaves in areas not returned to federal control by January 1, 1863, “then, thenceforward, and forever free.” His Emancipation Proclamation exempted areas occupied by Union forces and the forty-eight counties forming West Virginia. The transformation of war aims to include ending slavery encouraged more slaves to escape to Union lines and enlist in the federal army.

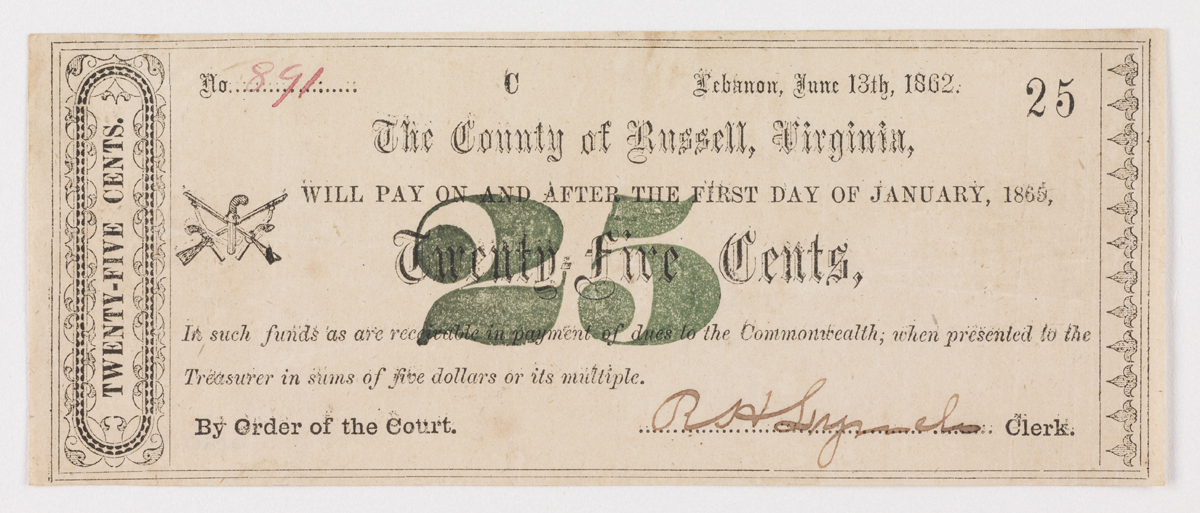

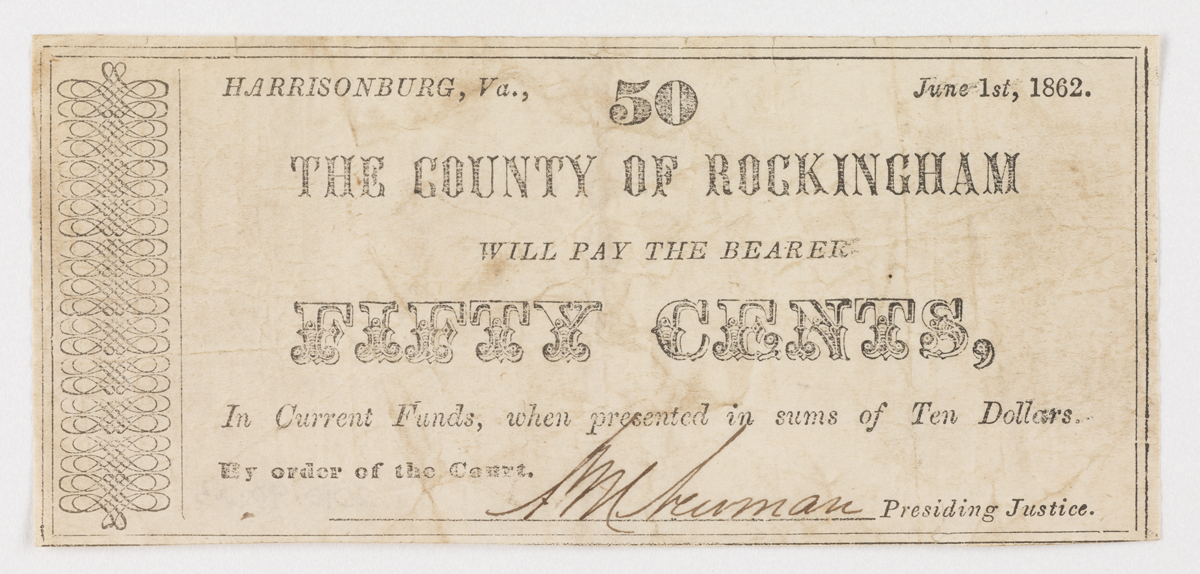

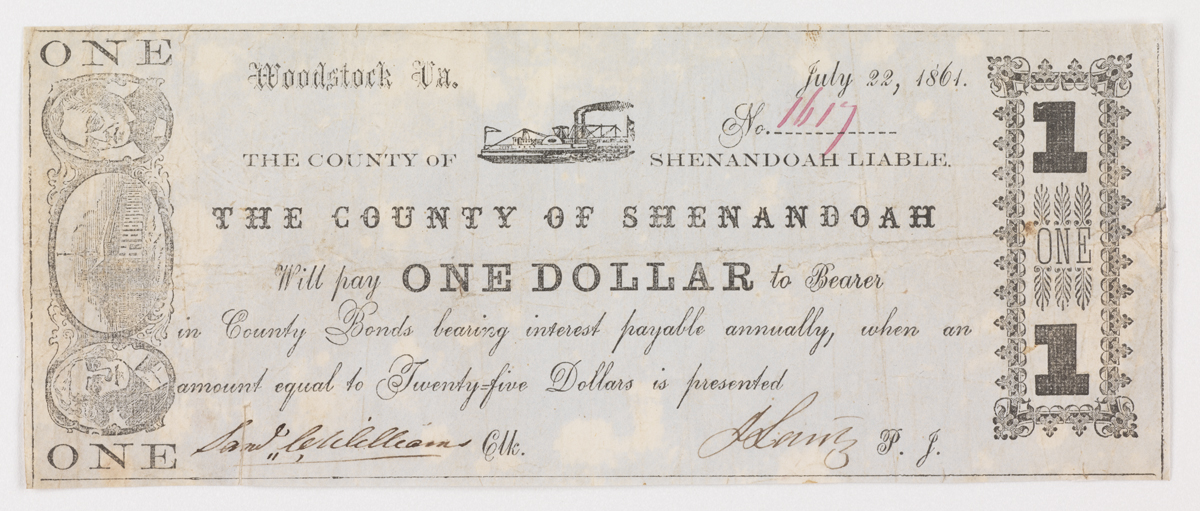

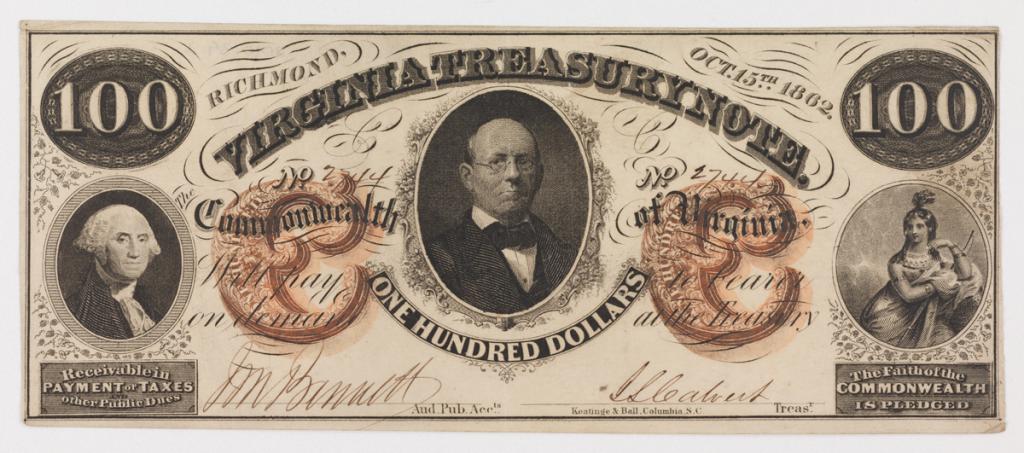

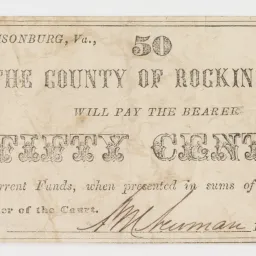

Confederate Currency and the Cost of War

The primary way the Confederacy funded the war was by printing paper money. This contributed to runaway inflation that plagued the South throughout the war. In January 1863, a Richmond newspaper reported that the weekly cost to feed a small family had risen from $6.55 in 1860 to $68.25. By April 1865, prices in the South had increased by 9,000 percent.

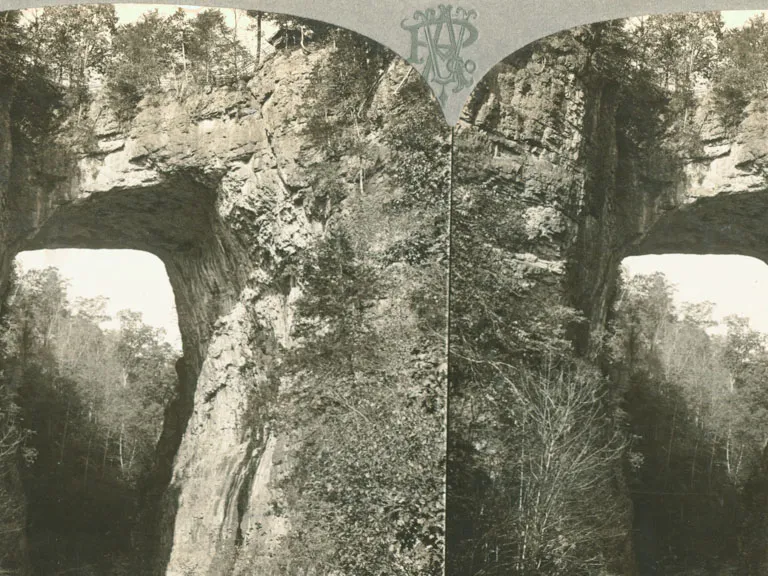

The total cost of the war to the Confederate states was approximately $3.2 billion in 1860 dollars. The devastation wrought in Virginia was enormous: burned or plundered homes, loss of crops and farm animals, neglected roads and ruined bridges. The value of personal property statewide decreased by nearly 40 percent—in large part because enslaved African Americans were no longer property.