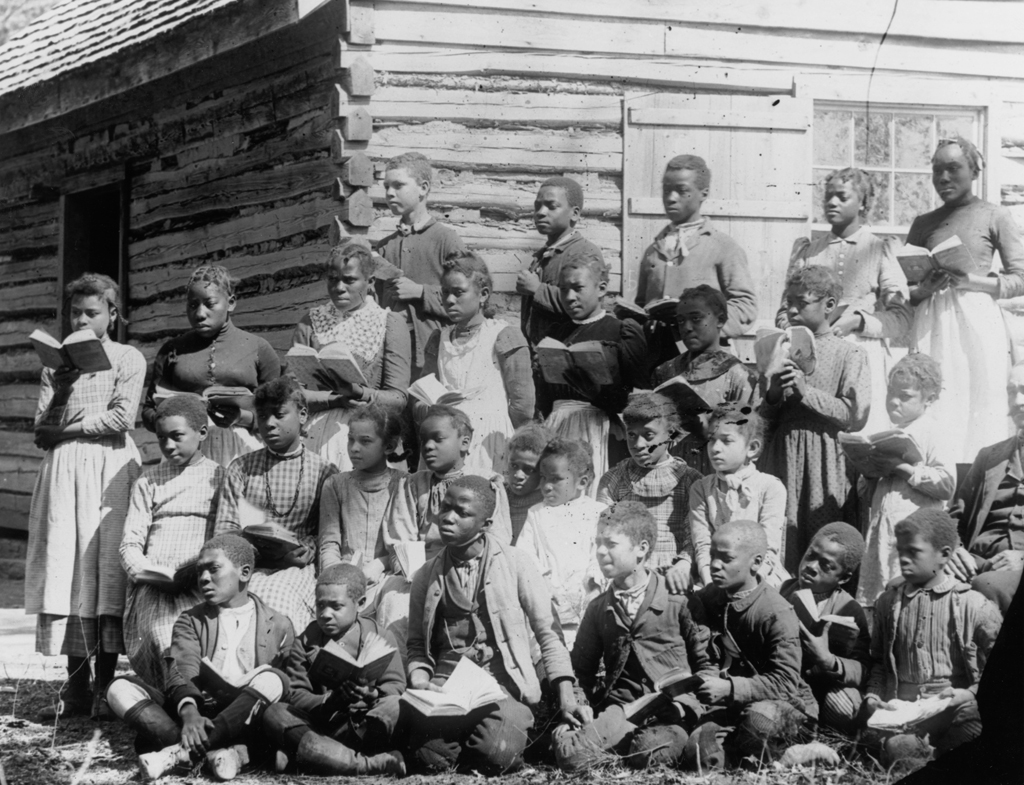

Beginnings of Black Education

Time Period

1861 to 1876

1877 to 1924

Topics

Black History

Civil Rights

Education

Few black Virginians received a formal education until public schools were widely established during Reconstruction. Public schools in Virginia were segregated from the outset, apparently without much thought or debate, on the widely held assumption that such an arrangement would deter conflict. Of course, public schools were segregated in many other states, both North and South. Southern black schools, however, were often dependent on funding from unsympathetic state and local governments controlled by whites, resulting in education programs with fewer resources for both students and teachers.