Massive Resistance

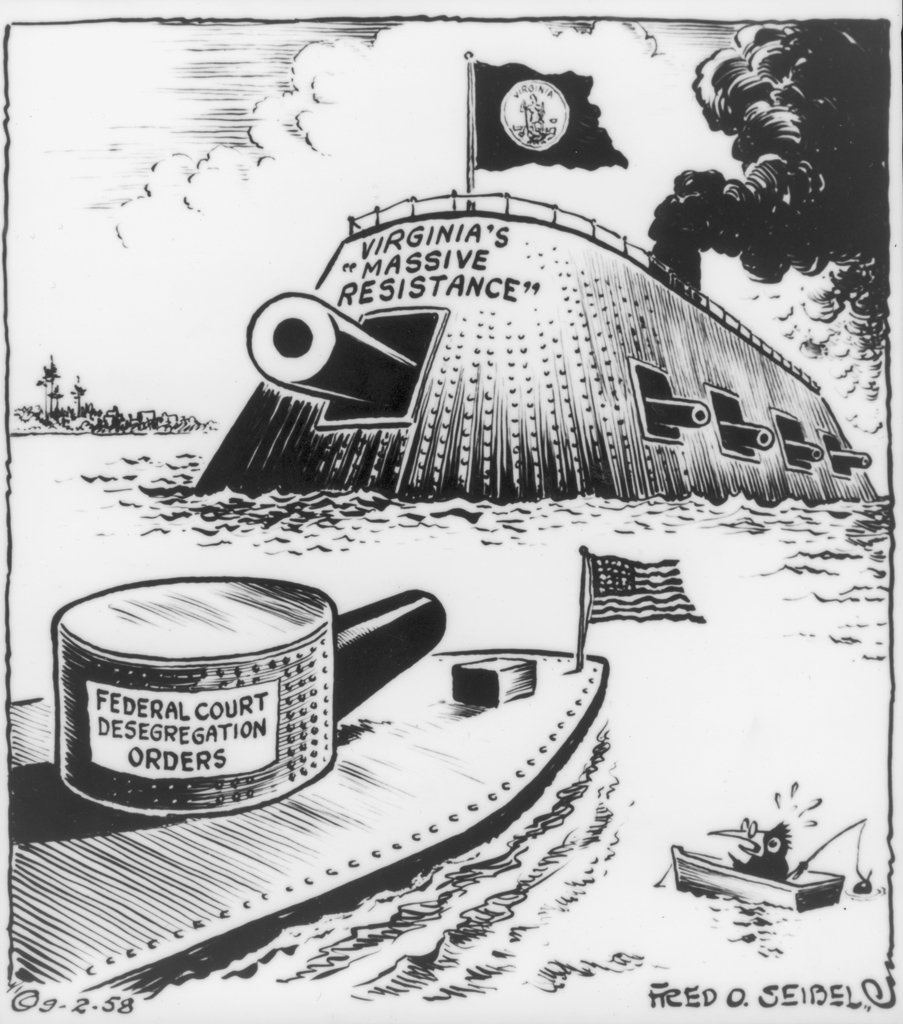

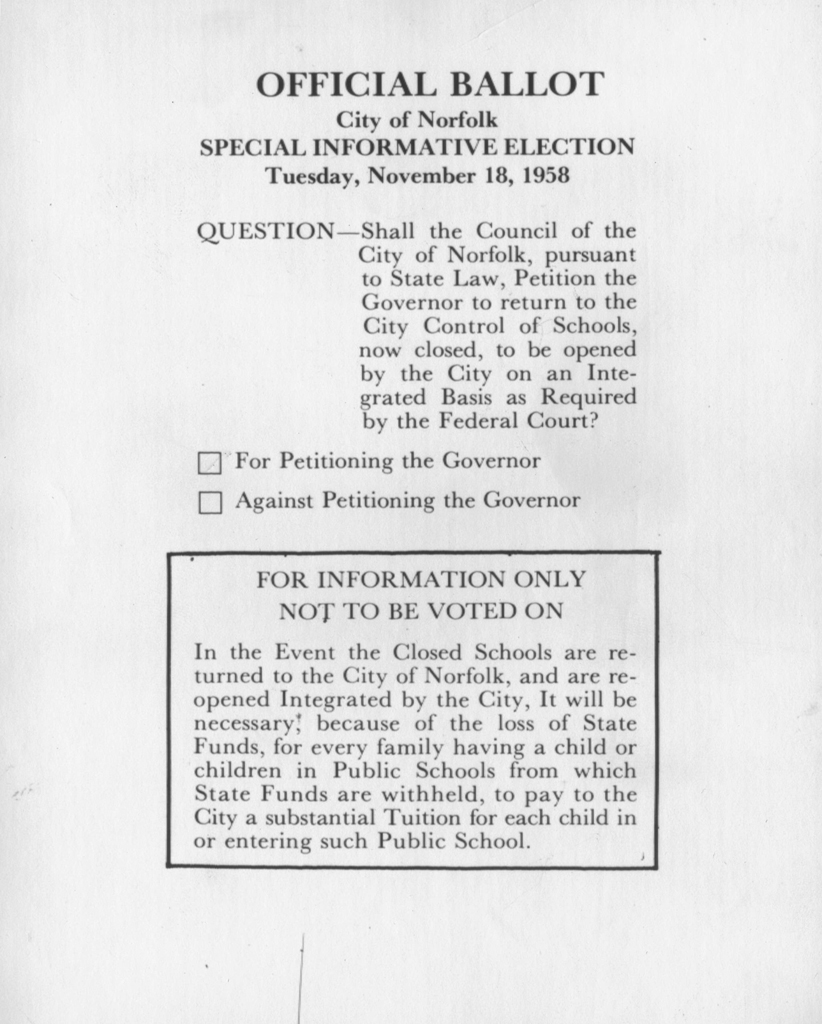

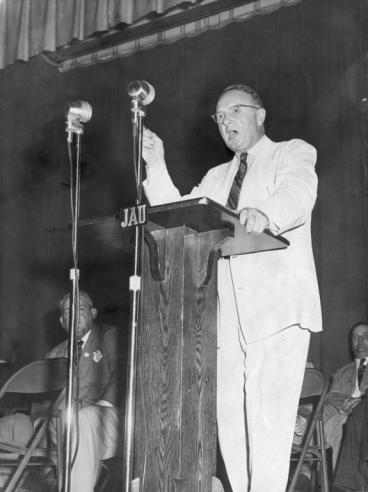

In 1954, the political organization of U.S. senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr., controlled Virginia politics. Senator Byrd promoted the "Southern Manifesto" opposing integrated schools, which was signed in 1956 by more than one hundred southern congressmen. On February 25, 1956, he called for what became known as Massive Resistance. This was a group of laws, passed in 1956, intended to prevent integration of the schools. A Pupil Placement Board was created with the power to assign specific students to particular schools. Tuition grants were to be provided to students who opposed integrated schools. The linchpin of Massive Resistance was a law that cut off state funds and closed any public school that attempted to integrate.

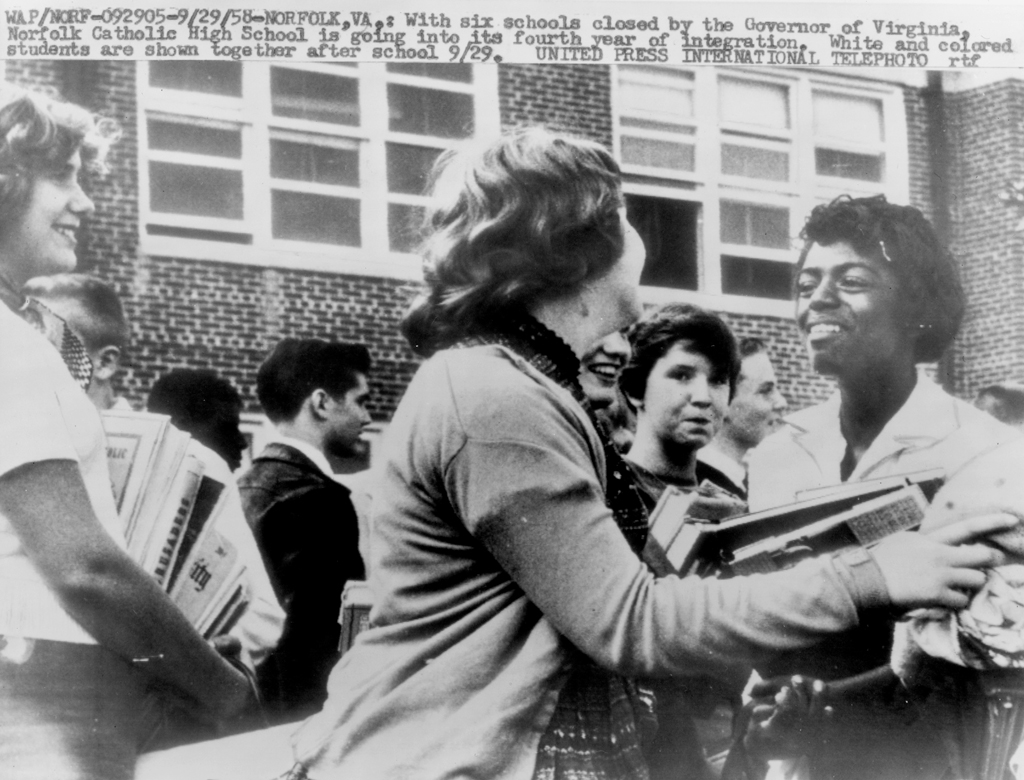

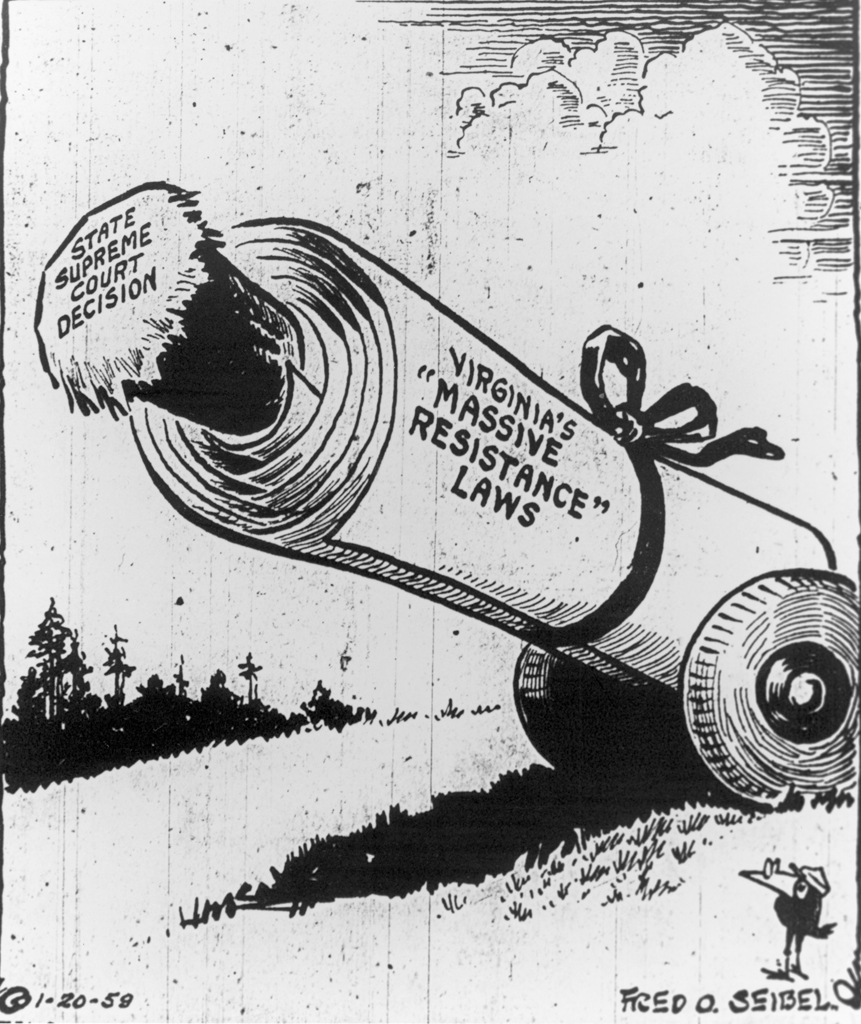

In September 1958 several schools in Warren County, Charlottesville, and Norfolk were about to integrate under court order. They were seized and closed, but the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals overturned the school-closing law. Simultaneously, a federal court issued a verdict against the law based on the "equal protection" clause of the 14th Amendment. Speaking to the General Assembly a few weeks later, Gov. J. Lindsay Almond conceded defeat. Beginning on February 2, 1959, a few courageous black students integrated the schools that had been closed. Still, hardly any African American students in Virginia attended integrated schools.