Voting Rights

To circumvent the Fifteenth amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guaranteed voting rights to Black men, the 1901–02 Virginia Constitutional Convention required voters to prove their understanding of the state constitution and imposed a

poll tax of $1.50 to be paid annually by registered voters. The white-majority General Assembly appointed all election registrars, who administered a deliberately complicated process to register voters. These measures achieved the convention’s desired result and reduced voting by poor whites, Black men, and Republicans dramatically. 88,000 fewer voters took part in the 1905 gubernatorial election in comparison to the 1901 election.

Although the 1902 Virginia Constitution remained in effect, officially, until 1971, its more restrictive voting measures were abolished by the courts and by federal legislation in the 1960s. Literacy tests—such as Virginia's requiring a "reasonable explanation" of any part of the state constitution—disappeared when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 stipulated that anyone with a sixth-grade education was presumed literate. The Twenty-fourth Amendment, ratified in 1964, outlawed poll taxes in federal elections. In 1966 the U.S. Supreme Court, in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, banned poll taxes in all elections.

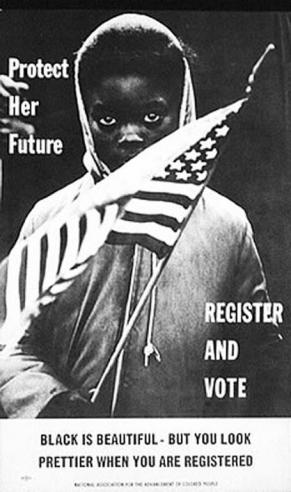

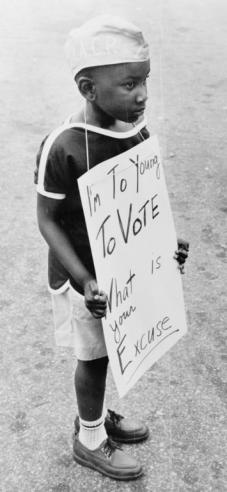

Events such as the 1965 "Bloody Sunday" in Selma, Alabama, persuaded President Lyndon Johnson to propose sweeping legislation—most notably the Voting Rights Act, which he signed into law on August 6, 1965. It authorized federal supervision of voter registration wherever fewer than half of eligible voters were registered, which included virtually all of the South. These efforts, supplemented by Black freedom schools, registration drives, and voter rallies, tripled the number of Black voters by 1968, and the number continued to grow thereafter.

In Virginia the results of enlarging the franchise were immediate, and soon led to an increase in elected Black officials. In 1967 Dr. William F. Reid became the first Black delegate in the General Assembly in 82 years. Hermanze E. Fauntleroy, Jr., of Petersburg, became Virginia’s first Black mayor in 1973. Lawrence Davies and Noel Taylor were elected mayors in Fredericksburg and Roanoke, respectively, in 1976. By 1977, Black members made up a majority of Richmond's city council; by 1985 there were seven Black members of the General Assembly. L. Douglas Wilder, in 1989, became the first Black governor elected in any state—and in 1992 Robert Cortez "Bobby" Scott became the first Black member of Congress elected from Virginia since 1888.

Newly enfranchised Black voters overwhelmingly supported Democratic candidates, believing that party to be more responsive to their various demands. In Virginia, the influx of Black voters helped propel the Democratic Party toward much more progressive policies. This development, coupled with opposition to school busing and affirmative programs, convinced many white voters to join the Republican Party, which moved toward more conservative policy positions.